Most Puffins will have watched David Lean’s 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai which is based on a novel published five years previously by French author Pierre Boulle.

Whilst both book and film are works of fiction, they are loosely based on the events that took place in Siam and Burma (now Thailand and Myanmar respectively) during World War II when Japan required an alternative supply route to link the two countries and aid its war efforts and imperialist expansion ambitions.

English: “Copyright © 1958 Columbia Pictures Corporation.”, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At this juncture a geographical correction note is required as the ‘River Kwai’ is a relatively modern moniker, only being adopted in the 1960s after the release of the film. The real bridge is located in the Thai town of Kanchanaburi and spanned what was the Mae Klong river but as the railway subsequently followed the Khwae Noi Valley, the bridge became famous under the wrong name. In the 1960s, the upper part of the Mae Klong was renamed the Khwae Yai (‘big tributary’) to appease tourists who started to appear in the country seeking out what they had seen in the cinema. Khwae became Kwai and the rest, as they say, is history.

Pre-WWII

The need for a railway had already been identified during the 1930s after Japan had gained a foothold in China during World War I, an act which ultimately led to war between those two countries. In response, both Britain and the USA imposed a trade embargo on Japan in an attempt to end the war and to also provide armaments and supplies via the 450 mile-long Burma Road across the foothills of the Himalayas from Lashio, a railhead in Burma, to Kunming and Chunking in China. The Japanese needed to cut this vital link ahead of their own invasion of Burma and obtain for themselves Burmese raw materials including tungsten and oil which were necessary to fuel their military goals, however the terrain around the Siamese-Burmese border was extremely mountainous and lacked roads that would allow the movement of the necessary levels of heavy artillery and tanks. All they could muster to support their Burmese campaign would be infantry and pack animals due to the need to traverse the track over the Three Pagodas Pass.

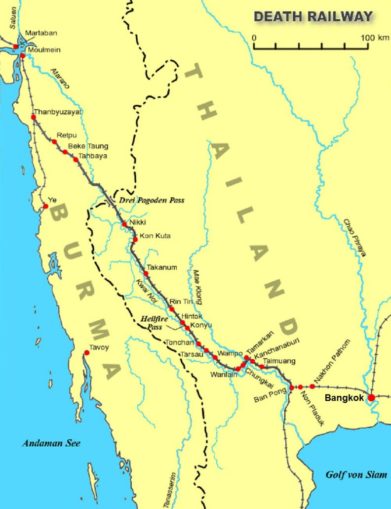

Their solution was to ship all military materials from Japan to Rangoon via Singapore and the Straits of Malacca, a journey of some 2,000 miles. These shipments could be picked off by the Allies operating out of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), attacking the Japanese convoys in the Andaman Sea so the only alternative available to the Japanese was to create a railway that would link Bangkok into the Burmese rail system.

This railway would eventually be built during World War II and was officially called the Siam–Burma Railway but become known by a more sinister name: The Death Railway.

WWII

Initial planning of possible railway routes started with a survey in 1939 by Japanese Imperial Headquarters with the conclusion that a longer route, from Bangkok to the Andaman Sea was the better of the options studied. These options had previously been considered by the British but were rejected because of the difficulties associated with the mountainous terrain, deep jungle, climatic extremes and the need for significant resources necessary for the construction of hundreds of bridges.

The first Japanese invasion of Burma took place just before Christmas 1941, via southern Thailand, with the goal of capturing and eliminating British airfields located at Victoria Point. The major thrust then took place via the Three Pagodas Pass with Rangoon falling in March 1942 and the Japanese set about a more detailed survey of the route from Kanchanaburi located to the west of Bangkok to the Three Pagodas Pass and then onwards to expand the scope of the survey to extend all the way to Thanbyzunat in Burma. Acting without instructions from the Imperial Command, Commanding Officer of Southern Region Army 2 Railway Control, Major-General Hattori ordered preparation for the construction to start without delay.

During the planning of the railway the Japanese railway engineers had to find solutions to the many problems previously identified by the British surveyors. One important consideration was the use of heavy construction machinery to aid jungle clearances, blast rock and cut timber. This solution was rejected on the grounds of the almost unfeasible logistics of transporting, using and maintaining such equipment with the added uncertainty that any machinery could be lost if sent via the Andaman Sea route.

The the scene was set for the employment of civilian workers and the formal construction order was issued in June 1942.

User:W.wolny, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Workforce

The majority of the estimated 60,000 labourers required to build the line and bridges would be sourced from the local populace who were promised good wages and clean living conditions for them and their families but it soon became obvious to the Imperial Japanese Army that additional resources would be needed if the railway was to be completed to their aggressive schedule and specification. Their solution was to bolster the workforce by providing up to 10,000 prisoners of war. However the IJA planners massively underestimated the work and attrition rate of the workers due to their poor working and living conditions and many tens of thousands more would eventually be required to complete the railway.

In April 1942, 1 Railway Materials Workshop set up base camps at Nong Pladuk in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma and began stockpiling construction materials and mechanical equipment. At the same time, the two railway construction units responsible for building the railway were moving to their respective base camps. 5 Railway Regiment was to start at Thanbyuzayat and work southwards and 9 Railway Regiment, with headquarters at Kanchanaburi, was to be responsible for building the railway northwards to Konkoita where the two lines would eventually join.

When the first construction engineers arrived in Bangkok on 13th May 1942, they found aerial photographs of the proposed route already available and within three days set out to begin the final detailed construction survey.

Five trainloads of British Prisoners Of War arrived in June, totalling some 3,340 men who formed the initial work party. They were sourced from Changi Prison in Singapore and forced into metal cattle wagons just 23 feet long, 28 men in each plus all of their personal belongings and Japanese equipment. For the four days and nights of the train journey to Ban Pong it was impossible for anyone to properly lie down to sleep, the only source of ventilation was a small sliding door which provided no relief from the searing heat conducted through the steel shell of the wagon and water/food provision wasn’t the highest priority of the Japanese.

Copyright Humbug 2024

The first tasks for these POWs was to start work on clearing the ground and build railway sidings, the base’s workshops and a POW transit camp for the work camps that would eventually be built along the railway as part of the northbound construction. In parallel to this, some 3,660 Australians plus British and Dutch POWs from Sumatra arrived in Thanbyuzayat to start work at the northern end of the line.

Why did the Allied prisoners (named “F Force”) go along with the plan to move them? Most of the groups leaving Changi had been told by the Japanese that they were going to areas where conditions were superior to those in Singapore’s notorious prison and the POW command was assured by the Japanese that:

- The climate of the new location would be similar to that of Singapore

- The prisoners would be distributed over seven camps, each of 1,000 men

- All camps would be in pleasant and healthy surroundings

- Sufficient medical personnel to staff a 300-bed hospital could be included

- As many blankets and mosquito nets as possible were to be taken by individuals and more of these items would be issued after arrival

- A musical band would accompany each group of 1,000 men

- Canteens would be established within 3 weeks of the arrival of the men at their destination

- No restriction would be placed on-the amount of personal equipment to be taken. Officers could take their trunks and valises

- Tools and cooking gear to maintain the Force were to be taken. This included an electric generating set for the hospital and Force HQ

- Transport would be available for the carrying of heavy personal equipment, camp and medical stores

- There would be no long marches

The reality was of course very different…..

© SWMBO & Humbug Slocombe 2024