Introduction

In 1967, as part of my Public Health Inspectors’ Education Board course, I remember attending a lecture given by Dr Moore, the then Medical Officer of Health for the City and County of Kingston-upon-Hull, on his pet subject of Epidemiology. I went into the lecture completely ignorant of the topic and came out fascinated by the examples of medical detective work used by Dr Moore to illustrate his teaching. Epidemiology is defined by the World Health Organisation as ‘a branch of medicine that relates to the study of the incidence, distribution and possible control of disease or determinants of health.’ I can only recall two of the examples that the MoH used, that of New York cook Mary Mallon (1869-1938) better known as ‘Typhoid Mary’ who in the early 20th century had continued to work after being identified as a symptomless carrier of Salmonella typhi infecting 53 people three of whom died and, closer to home, Dr John Snow whose pioneering investigative work during the London cholera outbreak of 1854 led to his being dubbed ‘the father of epidemiology’.

Who was John Snow?

John Snow was the first of nine children born to an upwardly mobile York labourer and his wife in what was then a poor and insanitary area of the city. From an early age John showed an aptitude for mathematics and science and in 1827, aged only 14 and supported financially, it is thought, by a wealthy uncle he was apprenticed to a surgeon-apothecary in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In 1832, Snow had direct experience of a cholera outbreak in the mining village of Killingworth where he treated many victims and in so doing gained what would prove to be valuable experience of the disease. From 1832 to 1835, Snow worked as assistant to two colliery surgeons in County Durham and Yorkshire before moving to London in 1836 where he enrolled at the Hunterian School of Medicine in Great Windmill Street. In 1838 Snow was admitted as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons and after graduating from the University of London in 1844 he was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in 1850 becoming a founder member of the Epidemiological Society of London later that year.

Dr Snow set up a practice as a surgeon/general practitioner at 54 Frith Street where he developed an interest in anaesthesia developing safer methods of administering ether and chloroform to patients and researching asphyxiation and the resuscitation of stillborn children. His interests also included gynaecology, rickets and mercury poisoning on which subjects he wrote papers. Snow’s reputation as an innovative anaesthetist grew and in 1853 Queen Victoria requested that Dr Snow provide her with anaesthesia during the birth of Prince Leopold, a service she was again to request in 1857 for the birth of Princess Beatrice.

Theories of Disease

In the mid 19th century, there were two theories regarding the transmission of disease known as ‘Miasma Theory’ and ‘Germ Theory’ although the latter was not fully developed or so called until Louis Pasteur published his findings in the 1860s. Miasma Theory held that diseases were spread by foul, environmental emanations in the form of mists and noxious vapours. Greek and Roman medicine was based on these beliefs and while they might seem ridiculous to the modern reader, they nevertheless eventually led to the cleansing of towns and cities by municipal sanitary control in the form of refuse disposal, sewerage systems and the removal of animal carcases. This ‘Sanitary Movement’ was enthusiastically supported by Sir Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890) whose crowning glory was his ‘Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Poor’ which was published in 1842 and drew attention to the atrocious living conditions of the urban working classes in the towns and cities of the Industrial Revolution. Another prominent advocate of Miasma Theory was Florence Nightingale who may have treated cholera patients at Westminster Hospital.

The alternative view held by Germ Theory advocates was that diseases were spread by ‘germs’ or micro-organisms that entered the body in water and food or by direct transmission from an infected person. Biblical and mediaeval practice of isolating lepers and the quarantine of sick people bore this out and in 1546 Fracostoro’s treatise ‘De Contagione’ had considered ‘germs’ as the cause of specific infectious diseases. The invention of the microscope by Antony van Leuwenhoek in 1676 had shown the presence of micro-organisms in samples of water leading to germ theorists’ belief that contaminated water spread diseases like cholera and typhoid.

Although the miasma versus germ debate would continue until the end of the 19th century, Danish scientist Peter Panum’s research into measles in the isolated community of the Faroe Islands in 1846 clearly showed person-to-person transmission, incubation period and conferred immunity. In 1876, Robert Koch proved conclusively that anthrax was caused by Bacillus anthracis and Pasteur’s work between 1860 and 1864 explained the pathology of puerperal or childbirth fever disproving once and for all Miasma Theory in its totality.

What is Cholera?

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal illness caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerea and it is spread by contaminated water and food. The disease is no longer endemic in the UK but still occurs in India, Pakistan, Africa, Asia and South America and is occasionally found in travellers returning from these countries. In 2011-2012 for example there were 37 UK cases, 27 of which originated in India and Pakistan. The disease is characterised by a rapid onset of profuse watery diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting causing severe dehydration followed by circulatory collapse and often death. With prompt modern medical treatment its mortality rate is in the region of 1% but this rises to more than 50% where treatment is delayed or non-available.

In the mid 19th century most medical people still adhered to the miasma theory but Dr Snow thought otherwise and in 1849 he had published an essay entitled ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ in which he opined that it was spread by mouth, a belief that was doubtless due to his having had experience of treating cholera victims in 1832 only one year after the first recorded outbreak in Britain in which 6,536 people had died. At the time Snow had noted that cholera victims’ lungs were not affected which, he reasoned, would have been the case had they been infected by breathing in ‘bad’ air. In the outbreak in 1848-49, 14,137 had died followed by a further 10,738 deaths in 1853-54. Snow suspected that cholera was due to the consumption of water contaminated with sewage discharged into rivers and water from wells polluted by leaking drains and cesspools.

The London Cholera Outbreak of 1854

In the 1850s, Soho was a grim place in which to live; it was badly overpopulated and lacked sanitary services. Chadwick’s 1842 report gives harrowing details of the conditions in which the urban poor lived. The sewers, such as they were, were primitive and were not connected to the main London system. As a result human, animal and trade waste ended up in the streets from where it gradually seeped under the houses forming cesspools. Sewerage that did find its way into the Thames was untreated and as the river was the source of much of the city’s drinking water, it was a disaster waiting to happen. Where river water was not piped to individual houses, local areas were served by communal wells from which water could be drawn by means of hand-operated pumps and thence be carried to the dwellings in containers.

The 1854 outbreak started in Southwark and Lambeth with very few cases initially being encountered in Soho. Then, on 31 August 1854 there was a sudden rise in case numbers followed three days later by the deaths of 127 people living in the vicinity of the Broad (now Broadwick) Street pump situated at the junction of Broad Street and Cambridge (now Lexington) Street close to the largest block on the map below.

What happened next has more often than not been over simplified as an investigation carried out by Dr Snow purely into the correlation of cases of disease with consumption of water from a particular pump but to do this is to trivialise his research. Snow’s main investigation related to properties served by the two water companies, The Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks Company and the Lambeth Waterworks Company both of which served the area with piped water taken direct from the Thames without further treatment. He was careful not to draw too firm conclusions from the Broad Street outbreak as three quarters of the residents had fled the area in the week after the outbreak had begun and his statistical sample was consequently small.

Dr Snow’s methodology was to interview local residents to determine their source of drinking water and disease status and to consult hospital and public records. To aid his investigation Snow used a map of the Soho area onto which he plotted the location of all the public pumps and then using differing sized blocks represented the frequency of disease in each dwelling with one or more cholera victims. In an effort to determine why some people in the area were completely unaffected he also tracked cases to local schools, eating places and public houses. One coffee shop owner who gave water which she obtained from the Broad Street pump to diners told him that nine of her customers had had cholera. Initially, Snow was puzzled as to why the local workhouse with 535 inmates had had no cases only to discover that it had its own well. A brewery in Broad Street also had no cases among its workers and Snow found that they were given an allowance of beer to consume throughout the day and although this was made with local water, it was boiled and therefore sterilised in the brewing process. Two other cases that puzzled him involved an aunt and her niece who lived some distance from the pump but who had both succumbed to cholera. It turned out that the aunt who had previously lived in Broad Street preferred the taste of its water to that where she currently lived and so had had a supply taken from the Broad Street pump delivered to her home on 31 August. Both women died the following day. Snow quickly concluded that as the Broad Street Pump was at the centre of the outbreak it was therefore highly likely to be the source of the outbreak.

On 7 September Dr Snow addressed the local Board of Guardians and persuaded them to remove the pump handle to test his theory that contaminated water from the Broad Street pump was responsible for the outbreak. This they did the following day upon which there was an immediately noticeable reduction in the number of cases. The authorities were however still reluctant to take further action to improve their sewers which they were adamant were not leaking. This left Snow with the conundrum that if the sewers weren’t leaking yet the pump was discharging contaminated water, where was the contamination coming from?

According to Snow:

On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the [Broad Street] pump. There were only ten deaths in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street-pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad Street, as they preferred the water to that of the pumps which were nearer. In three other cases, the deceased were children who went to school near the pump in Broad Street…

With regard to the deaths occurring in the locality belonging to the pump, there were 61 instances in which I was informed that the deceased persons used to drink the pump water from Broad Street, either constantly or occasionally…

The result of the inquiry, then, is, that there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump well.

I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St James’s parish, on the evening of the 7th inst [7 September], and represented the above circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day.

— John Snow (1854), letter to the editor of the Medical Times and Gazette

The answer was provided by local clergyman Reverend Henry Whitehead who had carried out his own interviews with local residents initially with a view to disproving Dr Snow’s theory but he had been unable to draw any conclusions other than that the outbreak was ‘a case of God’s divine intervention‘. Reading the minister’s report, Snow noticed that Whitehead had interviewed a woman who lived at 40 Broad Street whose baby had had diarrhoea and whose cloth nappies she had washed out throwing the faecally-contaminated water into a leaking cesspool only three feet from the Broad Street pump thereby polluting the water in the well.

At number 40 Broad Street… the story was as dreadful as anywhere. It was here that the little Lewis baby had died of exhaustion and diarrhoea just thirty-six hours after the outbreak began. Two hours after the child’s death, one of the Lewises’ fellow tenants, a twenty-five-year-old tailor, died of cholera in his first-floor back room. His wife followed him on the Tuesday morning. The tenant in the third floor back, another tailor, lingered long enough to be taken to hospital before he finally succumbed two weeks later. A second woman also died on the third floor, although local opinion was divided about how she met her end: some of the neighbours insisted that she died of fright rather than cholera, and as no medical help could be found for her in time, the matter was left undecided. There was no such ambiguity about the death of baby Lewis’s father, however. Forty-six year old Police Constable Thomas Lewis went down with cholera on 8 September, a week after his little daughter passed away, and he died on the 19th. Sarah [his wife] was left on her own to bring up her remaining two children. (Hempel, S. (2007). The Strange Case of the Broad Street Pump: John Snow and the Mystery of Cholera. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Personal Life

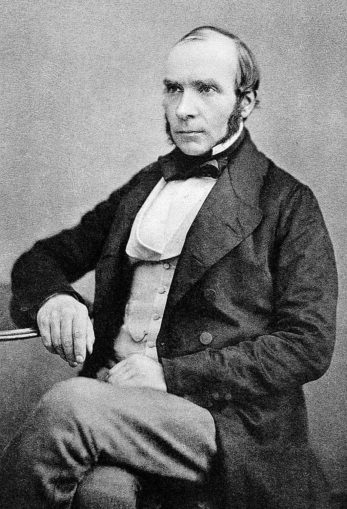

John Snow was a lifelong vegetarian and teetotaller who, not surprisingly, only drank pre-boiled water. When his health began to deteriorate due to renal problems shortly after his adoption of veganism he began to eat meat again and to take the occasional glass of wine to aid his digestion. Vitamin D deficiency could have been a contributory factor to his death from ‘apoplexy’ or what we now refer to as a stroke. In 2008, Professor AR Mawson of the Mississippi Medical Center suggested that from the evidence of the swollen fingers on Dr Snow’s right hand apparent in a contemporary photograph, his early death in 1858 at the age of only 45 could have been due to his repeated exposure to anaesthetic agents such as chloroform which he often tested on himself. Dr Snow was buried in Brompton Cemetery, London. He never married.

Dr Snow’s Legacy (and Myth?)

Today, John Snow is remembered mainly as the leading pioneer of epidemiology who through the application of revolutionary and painstaking scientific investigative methods single-handedly proved the link between the consumption of contaminated water and the transmission of cholera through whose decisive action the London cholera outbreak of 1854 was brought to an end.

Well, some of that is of course true and there is no denying John Snow’s incredible personal achievement in rising from such humble beginnings to treating no less a person than Queen Victoria herself. A plaque and replica parish pump have been erected to his memory in Broadwick Street close to the site of the original parish pump and a pub there has been named ‘The John Snow’ in his honour. Every September, a commemorative lecture on a public health topic is held by the John Snow Society and a college and lecture theatre have been named after him at Durham University and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine respectively. His character was even included in the 2019 television series ‘Victoria’ where the young queen personally assisted in having the parish pump handle removed. It should be noted, however, that the Queen’s own meticulously compiled diary makes no mention of this ever having happened and she refers to the number of deaths in the outbreak only in passing. So much for historical accuracy.

The truth of the matter is, however, somewhat more nuanced. At the time of his death, Dr Snow’s obituary in The Lancet read simply:

Dr John Snow – This well-known physician died at noon on the 16th instant, at his house in Sackville-street, from an attack of apoplexy. His researches on chloroform and other anaesthetics were appreciated by the profession.

There was no reference to his epidemiological work nor of his research into the mode of transmission of cholera. Recognition of his contribution would not come until the end of the century, long after his death. Furthermore, Snow was by no means the only person using epidemiological techniques at the time and while he has been remembered, people like Dr Robert Graves of Dublin and William Farr who also carried out epidemiological investigations have largely been forgotten. The research tools he used were in any case hardly novel and neither was Snow alone in postulating that cholera was a water borne infection. So why has he alone been remembered?

When Dr Snow’s treatise ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ was originally published in 1849 it received little acclaim but that was to change when it was republished in 1930 by Wade Hampton Frost, the first professor of epidemiology at the John Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore, USA, who described it as ‘a masterpiece in the ordering and analysis of evidence.’ Frost’s championing of Snow to bolster the relevance of the embryonic public health movement could be viewed as cynical exploitation of the ‘hero outsider’ who by providing a simple, environmental solution to a complex medical problem reinforced the role of this newly emerging discipline.

The irony of course is that the environmental improvements in sanitation and public health in London in the late 19th century were brought about not by the actions of the germ theorists but by those of the miasma theorists. The ‘Great Stink’ of July and August 1858 exacerbated the stench from human excrement and industrial waste in the Thames to such an extent that it was proposed moving Parliament to St Albans or Oxford in order to escape it and allow business to continue as normal. It was the fear of cholera caused by the noxious miasma that prompted the Metropolitan Board of Works to commission Joseph Bazalgette to plan a new sewer system for the city comprising 1,100 miles of additional street sewers feeding into 82 miles of main sewers initially to discharge the raw sewage into the Thames downriver at high tide. Sewage treatment works were introduced in the 1880s.

In conclusion

Whatever the ins and outs of the matter, John Snow’s is a truly fascinating story. It would be churlish to suggest that his achievements in his field were anything other than amazing. He rose from relative poverty by dint of the Victorian virtues of diligent study and hard work to become a celebrated physician who treated Queen Victoria during two of her confinements. Although it can be argued that his impact on the Broad Street outbreak was far less than was later claimed by individuals seeking to further their own agendas, Dr Snow nevertheless made an enormous contribution to the advancement of sanitation and public health. He is one of my personal heroes and he rightly deserves to be remembered.

© Tom Pudding 2022