The announcement over the two-carriage rattle-trap train’s tannoy told us this we’d reached the terminus and bid us ‘Welcome to sunny Skegness’. Bearing in mind this was December on the East Coast, these wry words raised a somewhat cynical chuckle from the few travellers.

Mr Sharpie and I had decided to embark on our adventure for no better reason than my having a day off from work, so up and out early and off to the station to buy our tickets for a 78-mile ride on the Poacher Line.

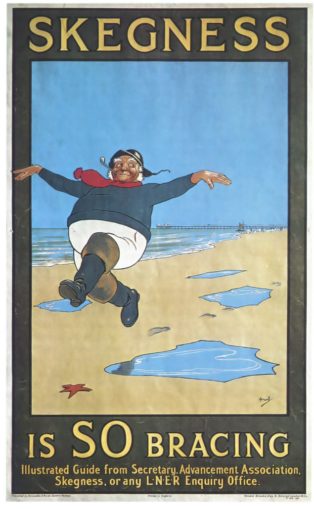

Figure 1: Skegness Is SO Bracing

© Paulpod, licensed under CC BY 2.0

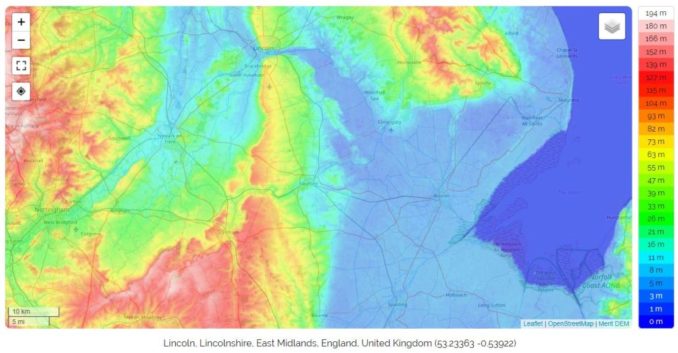

It’s a cracking journey, with pretty picturesque stations dotted along its length. The journey really demonstrates the geographical differences between the two counties as the landscape gradually transforms from Nottinghamshire’s hills and valleys to the half-wild and unforgiving, flat, fertile Fenland of Lincolnshire, with its low lying, level terrain, ditches and dykes, sluices and rivers, embankments and endless skies. It even provides a brief glimpse of Leicestershire along the way.

Figure 2: Topographical Map, Lincolnshire and the East Midlands

© OpenStreetMap contributors, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Lincolnshire county, or at least the area between the valleys of the rivers Humber and Witham, roughly from the Humber estuary to the Wash, was home to an Anglian tribe who, in the 6th century, established the Kingdom of Lindsey. They were the Lindisfaras (Old English: Lindisfaran). Thus, Lincolnshire as we know it today was once called ‘Lindsey’, and this is how it was recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book. A reminder once again of what an extraordinary history these Isles hold, and what a beautiful and varied country we inhabit.

Better still, the journey offers the opportunity to see both farm animals and wildlife along the way, as most of the route is resolutely rural. This time, we spotted horses aplenty, including what I think might have been a couple of gorgeous little Falabellas (too delicately boned to be the more common stocky Shetland ponies), some sturdy fuzzy-coated cattle, not Highlands, but pale-coated and horned, and a variety of different sheep breeds. Sadly, not a sign of the lovely lengthy locks of the Lincoln Longwool despite being aware that there are registered flocks of these beauties not a million miles from the line.

We saw the usual swans, geese and other waterfowl, the requisite Grey Herons amongst them, but also cormorants, which surprised me until I remembered that the waterways here are tidal. We spotted a soaring, spade-tailed Red Kite, several rather grumpy and damp looking Buzzards, and a delightful Kestrel with its spotted golden-brown plumage, hunting in the hedgerows alongside the track. We saw a few bunnies in the field margins and were fortunate enough to catch a brief glimpse of a group of Roe Deer in their dull winter coats, heads up and watching the train pass, but secure enough in the distance from the line not to take off running.

Around two hours after leaving Nottingham we stepped onto the platform, the excitement was palpable, two big kids in their element! Not long now and we’d be able to see the sea. A day at the coast and the weather forecast was pretty fair. Well, perhaps not good exactly, but it wasn’t dreadful. We were, we thought, well prepared, kitted out in the trusty Barbours and decent boots. Ready for our day of R&R, we’d put up with the anticipated crowds and enjoy a bracing beach walk in the salty seaside air. Our first surprise was the hustle and bustle and glorious sunshine… or rather, lack of it. Where the heck was everyone?

Figure 3: The Hustle and Bustle

© SharpieType301, 2021

As we set off for the High Street, we rapidly realised why sensible people were few and far between. It was perishing! Far from the 3º C temperatures the forecast had mentioned, this felt a whole lot colder, and the lazy wind cut through us, rather than bothering to go round. It was about now that I realised that bringing the gloves I’d left at home might have been a good idea. We needed a coffee and, as it was by now midday, were quite peckish. We decided to shelter from the elements at a traditional greasy spoon we’ve patronised in the past. I shan’t name it, for reasons which will become all too clear. Suffice it to say that it stands not a million miles from the inventively-named ‘Flippers’ fish & chippery.

We ordered and paid, and our hot drinks came quickly. Great so far. My breakfast was, as ever, a decent plate of bacon, sausages, fried egg, beans and tommies, with black pud and fried bread (yeah, yeah, health Nazis, we were on holiday!). Mr S. had decided to try the cheeseburger. Hmmm, when this arrived visions of ‘Falling Down’ sprang to mind. “See, this is what I’m talking about… it’s plump, juicy and three inches thick… now, look at this sorry, miserable, squashed thing”. Ah well, you win some, you lose some. The problems really came when Mr S. asked the woman behind the counter if he could use the loo.

He was met with a look of utter horror—but the man’s a maskless heathen! The answer comes, quick as a flash, no. He mentioned that he is exempt from muzzle-wearing, which he is on several grounds and has the card he can show them. The answer is still a hard-hearted no – you must be masked to use the loo. By now, slightly desperate, he asked why. Mistake. He was treated to a diatribe about lack of ventilation in their one and only cubicle, and the risk to other people, were he permitted through the portal of its porcelained places unmasked.

This, despite having just sat there unmuzzled, in the main part of the café with other people on neighbouring tables, for around half an hour eating our food. Logic, eh? Hmmm, apparently not. I’m amazed to be able to report that he was extremely restrained, only commenting as we stalked off into the cold that it was a shame that we had already paid.

Took a bit of the shine off the day. Hey ho, let’s go on a glove hunt instead. By now, it wasn’t only Baltic, it was chucking it down. Let’s make that a hat and gloves hunt. I don’t usually bother as I’ve a good head of hair, but it really was pelting down, and the wind had picked up. The nearby St Barnabas Hospice shop to the rescue and we headed off towards the sea.

Skeg really was deserted, and the only ‘happening place’ appeared to be the Hildreds Shopping Centre. We popped in to see whether it was purely somewhere to shelter out of the wintry weather (which it probably was) and, lo and behold, bumped into a Puffin. Look who we spotted on one of the benches!

Figure 4: It’s Bob C!

© SharpieType301, 2021

Though their Christmas decorations are quite attractive, it still wasn’t all that busy. It was nice to see that the safety of customers was firmly in mind, however (those floors get slippery with all that rain, you know), and a cheeky chappie with a clipboard was firmly in control!

Figure 5: Elf and Safety

© SharpieType301, 2021

Well, it couldn’t be put off any longer. It was time to brave the elements and go to see the North Sea… and beautiful it was too. We had the beach completely to ourselves and the added joy of it having stopped raining (albeit briefly). We were not at all surprised to see that, despite the lull, there was a large dark cloud on the horizon piddling down on some luckless soul out there in the chilly waters.

Figure 6: Looking Eastwards

© SharpieType301, 2021

The light was beginning to fade as we headed back from our walk, and for once the ‘Dog Free Zone’ sign was rather unnecessary. Looking northwards towards the lights of the Victorian boardwalk of Skegness Pier, stretching from the edge of the beach 118m (372 ft) to the water’s edge, there wasn’t even a seagull to be seen. They doubtless had more sense that we did.

Figure 7: Dog Free Zone

© SharpieType301, 2021

As we walked back along Tower Esplanade towards the Clock Tower, past the Atlantis Adventure Crazy Golf with its 18th hole inside a lit-up fantasy submarine, and the Lifeboat Station, we didn’t see a soul. A few disgruntled starlings were trying to stop themselves solidifying atop the lights, and I can’t help but think poor old perishing Poseidon wished he’d put his pullover on—that trident didn’t do much to keep him warm!

Figure 8: A Few Cold Inhabitants

© SharpieType301, 2021

By now, we were absolutely freezing and distinctly tired. Time to amble back to the railway station and head for home. Skegness had another surprise for us though, a glorious sunset to draw us back home along the rails to Nottingham. The colours were simply wonderful, and the rapidly shifting clouds meant it changed by the moment. It almost made us feel warmer, just looking at it.

Figure 9: Skegness Sunset

© SharpieType301, 2021

Now this hasn’t been all that much of a postcard, so I thought I’d leave you with a whistle-stop tour of the rather special Poacher Line, as we wend our weary way westwards.

Named after the unofficial county anthem of Lincolnshire, the traditional English folk song “The Lincolnshire Poacher” which many here will recognise, the Poacher Line covers most of the train route between Nottingham and Skegness.

When I was bound apprentice in famous Lincolnshire,

I serv’d my master truly, for nearly seven odd year,

Till I took up to poaching, as you shall quickly hear.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

As me and my companions were setting up a snare,

The gamekeeper was watching us – for him we did not care,

For we can wrestle and fight, my boys, and jump o’er anywhere.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

As me and my companions were setting four or five,

And taking on ’em up again, we took a hare alive,

We plopped her into my bag, my boys, and through the woods did steer.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

We threw him over our shoulders, and wandered through the town,

We called into a neighbour’s house, and sold her for a crown,

We sold her for a crown, my boys, but I did not tell you where.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

Bad luck to every magistrate that lives in Lincolnshire,

Success to every poacher that wants to sell a hare,

Bad luck to every gamekeeper that will not sell his deer.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

In truth, the Poacher Line originally covered only the section between Grantham and Skegness but, now part of the award-winning Community Rail Network, the nineteen stations along the route from Nottingham to Skegness are looked after by a team of tireless volunteers, local groups, ‘friends’ and partners, working hand-in-hand with the rail industry. One of sixty-one Community Rail Partnerships across the UK, a volunteer-led grassroots movement established in the late 90s, the Partnerships work with local communities to benefit them, help halt the decline of branch lines, and celebrate the great feats of Victorian engineering that are our railways.

Figure 10: The Poacher Line

Copyright of and reproduced with the kind permission of the Poacher Line CRP, 2021

So, let us begin… Of Skegness, we’ve already seen a little, although it is not where it originally was. The ‘old’ Skegness, the name deriving from the Old Norse words Skeggi (beard or bearded one) and ness (headland), was somewhat farther east, nearer to the mouth of The Wash. That small mediæval fishing village was lost to the sea after violent storms in the 1500s broke through the natural sea defences. The town on its present site was rebuilt, again as a fishing village, but began to grow as a holiday resort in the late 18th century.

Three miles towards Nottingham, the first station is Havenhouse (originally called ‘Croft Bank’). Blink, and you’d be forgiven for missing it. Of more interest is the next stop, at Wainfleet All Saints, opened by the Wainfleet and Firsby Railway for passenger traffic on 24 October 1871. In fact, you see the Grade II Listed Wainfleet Signal Box before you reach the station. Built in 1899, it retains its original Railway Signal Company frame of 25 levers to control the signals.

A pretty little market town, likely the former Roman settlement of Vainona, it was once a port, and stands between the rivers Steeping and Lymn. Puffins might know of it from the family-run Batemans Brewery, housed at the Salem Bridge Mill since 1874.

Figure 11: Bateman’s Austin FF K140 flatbed

© SharpieType301, 2006

You’ll doubtless have seen their Christmas special ‘Rosey Nosey’ pumps at some point, and I’ll admit that I can vouch for their ‘Triple XB’, having been on a brewery tour some years ago. I quite fancy trying their ‘Salem Porter’ but haven’t yet.

Next up is Thorpe Culvert, the little station serving Thorpe St Peter, one of 13,418 places listed in the Domesday Book. The lovely sandstone parish church, a Grade I listed building dating from 1200 is, of course, dedicated to Saint Peter.

Then a sharp turn in the tracks in the middle of nowhere, the Firsby Curve. This is all that remains of Firsby East Junction on the Skegness line with its once substantial country station, when it was one of the busiest stations on the East Lincolnshire Railway. The station had three platforms each two hundred metres long, the tracks were crossed by a substantial footbridge and most of the station was covered by an ornate cast-iron and glass canopy.

During WWII, it was an important staging point for both RAF and USAF airmen travelling to and from the nearby RAF Spilsby, one of around fifty airfields operational in the county—a busy old place with, I imagine, a lot of tales to tell. Ah well, the 1960s Beeching cuts (when 4,500 miles of railway line and 2,128 stations were closed, and 67,000 British Rail job cut, all in the name of saving money) put paid to all that.

By now, it’s properly dark and, off to our left, the most beautiful thin orangey sliver of moon, rising above the flat land accompanied by the bright dot of Venus. This section of the track runs straight as a die, southwest to Boston, and our arrival is marked by the first glimpse of ‘The Stump’, St Botolph’s Church. The largest parish church in England, it is notable because, as the surrounding land is so flat, it’s visible as a significant landmark from miles away. Boston, which lies on the Prime Meridian, due north of Greenwich, is so named after a Saxon monk named Botolph, who chose a site on the banks of the River Witham to establish a monastery in AD 654, next to an existing settlement.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, after the Norman Conquest, Boston grew into a thriving town and port. Indeed, for a period in the 13th century Boston was the leading port in England after London. Its wealth was largely based on exporting wool from monastic and other estates, lead from Derbyshire and salt from the Lincolnshire coast, whilst importing exotic goods such as wines, furs and spices. Boston had become important to the Hanseatic League, who dominated commercial activity in northern Europe from the 13th to the 15th centuries.

By the early 1600s, during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I then King James I, Puritan non-conformists with strong links to Lincolnshire wanted the freedom to worship God away from the constraints of the Church of England. Fleeing persecution, they went first to The Netherlands, sailing from Boston. These English Separatists, known as the Ancient Brethren, later chose to set sail for America in 1620, on the Mayflower in search of a better life. Ten years on, another group of Puritans left Boston for America. The settlement they founded was named after the English town from where many of its most influential settlers had originated.

Boston’s more recent history gives us two of my favourite buildings in the town. The first of these is the 1877 three-storey red brick Swan House on Trinity Street, complete with a large stucco statue of a swan on the roof above the entrance. Now converted into flats, this was the former feather factory of E. Fogarty and Co. Ltd. (prior to that F. S. Anderson & Co.). Feathers from geese raised in the Fens, plucked twice a year, were heat-purified here, then used to stuff pillows.

Figure 12: Swan House, Boston

© SharpieType301, 2018

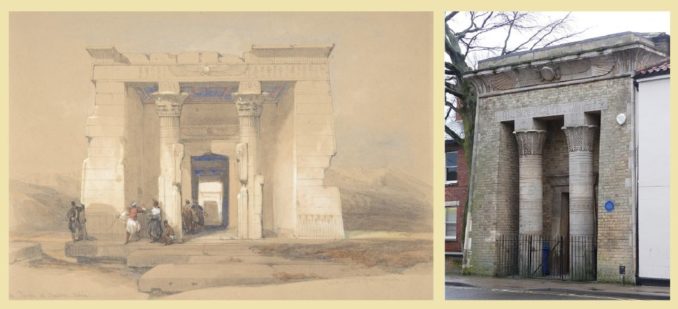

The other one is simply bizarre. It’s not very big, but it makes up it for in sheer kookiness. It sports two massive columns with palm-leaf capitols, a winged disc of the sun supported by asps over the doorway and is complete with hieroglyphic inscriptions. Built around 1860, in the Egyptian Revival style, it’s the Boston Masonic Hall. Modelled on the 1848 David Roberts watercolour painting of the Temple of Dandour in Nubia, it’s as out of place as tits on a bull, but it makes me smile.

Figure 13: The David Roberts Watercolour and Freemasons’ Hall

Public Domain, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and © Stephen Richards, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Leaving Boston, the next station on the Poacher Line is Hubberts Bridge. What is there to say about this except that this small village’s name derives from the bridge crossing the South Forty-Foot Drain. This is a favourite part of the journey for me, when it’s light, as this section of track runs right alongside the drain for a considerable distance. Sometimes referred to as the Black Sluice Navigation, and dating back to the 1630s, the South Forty-Foot is the primary land-drainage channel for the Black Sluice Level in the Fens, formerly known as the Lindsey Level.

Swineshead, is the next stop, although it’s easily missed. Not much to see here now, but this was the home of the Abbey of St Mary, a Cistercian monastery, founded in 1134. Its claim to fame was that King John spent a short time here shortly before his death at Newark Castle in 1216, after losing his belongings, including the English Crown jewels, as he crossed one of the tidal estuaries which empties into the Wash in the Fens.

Next is Heckington. The station has a lovely old-fashioned feel where the level crossing gates are still opened and closed manually, and still makes use of its sweet Grade II listed signal box and semaphores. The old station building now houses a transport museum. It’s a beautiful, bustling village with the world’s only 8-sailed windmill (there were only seven of the type ever built in Britain). Standing six floors high, visitors can go all the way up to the top. This Grade I listed structure was built in 1830, originally with just five sails, with the others being added by John Pocklington when it was repaired after storms in 1890.

It was still working away, producing some fabulous bread flours until 2018 when another fierce storm caused significant damage. By now, you might have noticed a bit a theme, in the history of severe weather and destruction in these parts. Climate change, eh Greta?

Heckington is also home to the aptly named 8 Sail Brewery, nestling in the shadow of the windmill. Established in 2010, The brewery seeks to recreate some of the most popular traditional beer styles as well as brewing beers to suit modern tastes. I’ve not tasted their products, but the beers have been winning awards so might be worth a look. Being a dark mild gal, I rather like the sound of their Black Widow.

Sleaford is the largest town in the district, but was first settled in the Iron Age, sometime around 50 BC and 50 AD. It is thought that Old Sleaford could have been the largest settlement in the Corieltauvian territory, and was the site of a mint, striking coins in gold and electrum (alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper) like the one shown below, in…mint condition.

Figure 14: An Electrum Stater (probably minted at Sleaford, mid-1st century BC)

Public Domain, Bedoyere at English Wikipedia

The site for the original settlement was to the northeast of the railway station where a Later Prehistoric trackway crossed the River Slea. Trackways were vital in marshy areas, as they connected the fen ‘islands’ scattered across the marshland. The trackway here may well have linked into the ancient east-west trading route between the Dorset coast and the Wash. Perhaps the best-known section of this track is the Ridgeway in Wiltshire, possibly the oldest ‘road’ in Europe—a place where Stone Age man (and woman!) once trod, even before Britain became an island.

More recently, the largely agricultural countryside around Sleaford was a major barley producer. Allowed to ‘steep’, ‘germinate’, and then ‘kilned’ to produce malt, barley is key to brewing beer. This abundant local resource, a natural spring on the site providing good quality water, and excellent rail links (the neighbouring station was erected in 1857), attracted the Bass Brewery to Sleaford from Burton upon Trent around 1901.

The spectacular Bass Maltings, all eight massive identical six-storey, interlinked malt houses (known as pavilions), were the largest complex of floor maltings in England. Built in red brick, with roofs of good Welsh slate, standing alongside the rail tracks, and with their own rail sidings, they are unmistakeable. Their scale (each covers an area the size of six football pitches) and the intricacy of their architecture is extraordinary, even though the site is but half the sixteen-malt house plans originally proposed.

They’ve been given a Grade II* Listing, being recognised as “particularly important buildings of more than special interest“. Sadly, the maltings, where in addition to their wages workers earned three pints of beer per day, closed in 1959. The buildings have stood derelict since 1990, poorly maintained, vandalised and subject to more than one arson attack. Parts of three malt houses are severely damaged and are amongst several buildings now roofless.

My memories of the town stem from miserable wintertime phone calls to my ex, whilst he was based at Royal Air Force College Cranwell for his Officer training with OACTU. As Sleaford was the closest, er… only, point of ‘civilisation’ for miles, as a London lad he wasn’t best impressed. However, this period of life did give me an appreciation for the Royal Air Force Swing Wing Band and the shit-kickers who make up the RAF Regiment. Incidentally, “The Lincolnshire Poacher” has also been adopted as the quick march of the College.

The line continues towards the west, and the next station is Rauceby. Oddly, this isn’t in the village, not even on the outskirts, but lies around half a mile to the south of present-day South Rauceby. This, in turn, is about a quarter of a mile from North Rauceby. These two villages were once just one, the mediæval settlement being considerably more extensive than nowadays (earthwork remains are visible on aerial photographs). It is thus listed as a deserted mediæval village (DMV), and the wane in population may have been the result of the Black Death in the mid-14th century, though could have declined earlier due to soil exhaustion from heavy reliance on a single crop, typical of the Middle Ages.

Rauceby’s main claim to fame is that Archibald McIndoe, a New Zealander, and a brilliant reconstructive plastic surgeon, ran the WWII Crash and Burns unit at Orchard House, No 4 RAF Hospital Rauceby, for RAF Cranwell. This acted as a satellite plastic surgery centre, overseen by McIndoe’s team, who also worked out of the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead.

McIndoe was the founder of the Guinea Pig Club (the inspiration for the more recent CASEVAC Club). Established as an informal social (a.k.a. drinking) club in 1941, during their long recoveries, the Club was named with typical Forces black humour. Its members were the badly burned aircrew recuperating from experimental plastic surgery after horrific injuries sustained during service in WWII, together with their surgeons and other medical staff.

Figure 15: Sir Archibald McIndoe toasts a former patient and his new bride

McIndoe was remarkable man, and a bit of a maverick. He challenged, sometimes quite vocally, the existing perception that disabilities were life-limiting and realised how important rehabilitation and social reintegration back into normal life was for the men he treated. Many had disfiguring and devastating injuries caused by exploding highly flammable aircraft fuel—so-called ‘Hurricane burns’—but treating these external injuries was not enough. He recognised that you have to treat the deep and persisting trauma on the inside spawned by both the original event and the lengthy treatments as well. He described the Club thus:

“…the most exclusive Club in the world, but the entrance fee is something most men would not care to pay, and the conditions of membership are arduous in the extreme”

The Club’s members were a bunch of seriously tough cookies, and continued to hold reunions right up until 2007, with McIndoe remaining President until his death in 1960. No soy-boys these men. Its first Secretary had severely burned hands, so Club records were designed to be brief, and thus easy to read. The first Treasurer was a pilot with dreadful burn injuries to his lower limbs. Half in jest, it was said he was selected for this job so he couldn’t leg it with the Club’s funds!

Ancaster was our next station, once the first after Grantham on the original Poacher Line to Skegness. Although there is evidence of prehistoric and Iron Age settlement here, as the name suggests, it’s an old Roman fortress town (any town with ‘chester’, ‘caster’ or ‘cester’ will be Roman, as the word comes from the Latin word ‘castrum’, a fort). It lies on Ermine Street, an important Roman road linking London (Londinium) to Lincoln (Lindum Colonia) and York (Eboracum) in the north.

The village has a lovely Grade I listed parish church, sadly now permanently closed. It was built on the probable site of a Roman temple and dedicated to St Martin. Many churches constructed on Roman sites are dedicated to this warrior saint. Martin was born in Pannonia (present-day western Hungary). He served in the Equites (Roman cavalry) in Gaul, converted to Christianity, and was consecrated as Bishop of Caesarodunum (Tours) in 371. As well as some Roman statuary, there are the remains of ‘grotesques’ from the Middle Ages—a ‘mouth-puller’ Green Man in the church’s vestry, and one displaying a rather different part of the anatomy, a Sheela na gig pagan fertility symbol, on the north side of the tower.

Figure 16: An example of a Sheela na gig

© theilr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Onwards we trundle to Bottesford, the only station on the Poacher Line located in Leicestershire. The village sits in the narrow finger of the county, pointing nor’-nor’-east between Nottinghamshire to the west and Lincolnshire the east, through which the line runs for only just over a mile. The tall, slender, almost delicate, octagonal crocketed church spire you see as you pass through is that of St Mary the Virgin, the ‘Lady of the Vale’. Inside you’ll find a memorial to Henry and Francis Manners, heirs to the 6th Earl of Rutland. The boys’ deaths at a young age were attributed to sorcery at the hands of the females of the Flowers family, the Witches of Belvoir.

On a cheerier note, this large medieval church, dating back to the 12th century, is now home to a family of peregrine falcons. Had it been light, I’d have loved to catch a glimpse of these beautiful birds of prey. Belvoir Castle, the seat of the Dukes of Rutland, home to the murdered boys, and also the Duke of Rutland’s Hounds (who now practise Trail Hunting rather than pursuing Reynard and his mates) is just a few miles further south.

Aslockton is next, birthplace of Thomas Cranmer in 1489). Cranmer became the first protestant Archbishop of Canterbury thus the village has a special connection with the Reformation. Little now remains of Cranmer’s Chapel (the Holy Trinity chapel), less still of the motte-and-bailey fortress, Aslockton Castle, built in the 11th or early 12th century. Only a few earthworks remain, including part of the motte, known as Cranmer’s Mound, where he used to sit as a child.

Now less than ten miles away from Nottingham and a very welcome cuppa, we stopped briefly at Bingham station. What can I say about this small town, largely overshadowed by Nottingham to the west and Newark to the north? Well, it still holds open-air markets, having held a market charter since 1341. Although the site has shifted over the years, it probably developed from the Roman fortress of Margidunum.

This lay close to the Fosse Way, one of England’s greatest Roman legacies, a road which runs diagonally across the country between Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) and Lincoln (Lindum Colonia). Laid as a military road in the first phase of Roman occupation, after the Emperor Claudius landed in Kent in AD 43, this road one of the straightest across England, effectively marked the western frontier of the Roman province, and its length was peppered with numerous small military stations.

The dark red colour of the Triassic red shale cliffs along the River Trent gave Radcliffe-on-Trent its name. We’ve already met its most famous son in one of my other articles, although even he upped sticks and left the place. John Boot, the founder of Boots the Chemists, was born in Radcliffe in 1815. He worked as an agricultural labourer before moving to Nottingham in 1849 to prepare and sell herbal remedies. The rest, as they say, is history. The village has a long history of settlement, certainly from the Bronze Age onwards, and likely before that. Its position, on dry, flat ground near to a supply of water made it a likely spot for a short-term hunter-gatherer camp, and the fertile land and workable soils would have encouraged longer-term settlement.

The last stop on our seemingly endless journey home is Netherfield. Originally, common pasture known as the Nether (or Lower) Field of Carlton in the Willows, building in Netherfield only really began in around 1840 as the railway and mining communities developed. The Nottingham to Grantham railway line brought steam engine sheds, sidings, and the largest railway marshalling yard in the country (now the Victoria Retail Park). In 1874, the Great Northern Railway Company (GNR) erected a row of twelve houses, called Traffic Terrace for its workers, followed in 1881by a second row, Locomotive Terrace. By 1901, Netherfield’s population had grown to 4,646.

Perhaps Netherfield’s most exhilarating moment, if that’s the word, came at just after 1am on Sunday, 25th September 1916, when the unmistakable deep-throated drone of a Zeppelin was heard approaching. The warning siren sounded, sending the population into a panic, extinguishing lights that might help guide the airship. Unfortunately, the railway companies didn’t emulate this sensible approach as the blackout did not apply to them.

Led by Kapitänleutnant Hermann Kraushaar, the single, steel framework Zeppelin L-17 with its 22-man crew made a beeline for and lined up on the three train stations, which were still brightly lit.

Figure 17: Engine gondola of a Zeppelin airship, by Felix Schwormstadt

© Public Domain, Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

There followed a brief but destructive 15-minute raid. Kraushaar’s crew, from around 14,000 feet, dropped a clutch of nineteen bombs (eight explosive and eleven incendiaries) in a line towards Nottingham city centre. The first bomb landed at the corner of Cross Street and Dunstan Street in Netherfield, demolishing six houses, the last fell in Mapperley. Astonishingly, though there was considerable damage to property across the city, there were only three fatalities and seventeen injured. At the inquest, it was ruled that Alfred Taylor, Rosanna Rogers and Harold Renshaw, had been ‘murdered by person or persons unknown, through the explosion of bombs dropped from an airship’. However, the jury went on to blame the local railway companies for keeping their lights on and exposing the city to the ‘risk of attack’ in the first place.

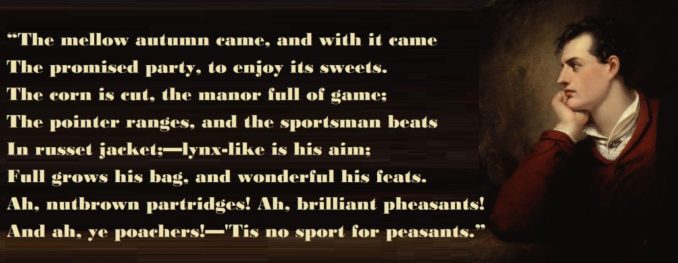

And finally, we reach Nottingham, of which you have heard much from me in the past, and doubtless will again. I shall leave you at the end of our adventure with some words on poaching from a ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’ local lad, The Right Honourable Lord George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron.

Figure 18: Byron’s Portrait by Richard Westall

© SharpieType301 2021