“Seven years ago today — on November 8, 1942 — Anglo-American forces landed on the coast of French North Africa between Casablanca and Algiers. It was the beginning of a campaign which could have been successfully concluded in a few weeks, but which dragged June on for four months.

“The story of the war in Tunisia is very largely the story of the First Army — a new army, small in numbers, well trained, but lacking in experience, which nevertheless triumphantly endured some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

“Its life as an army was short: few, except those who served in it, remember it. John Alldridge, who last summer retraced the story of the 5th and 8th Armies in Italy, has returned to North Africa to revive memories of a great feat of British arms. He will be revisiting obscure towns and villages which will one day be proudly carried as battle honours — Longstop Hill, Medjez-el-Bab, Tebourba, Tunis.

“Today, on the seventh anniversary of the North African invasions, he writes from Algiers.” – Manchester Evening News, November 8 1949

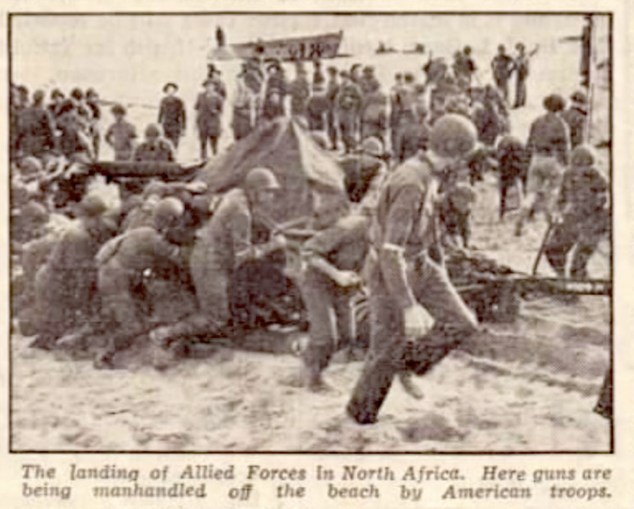

The landing of Allied Forces in North Africa,

Unknown photograoher – © 2023 Newspapers.com

Algiers, Tuesday

It started here in Algiers. But, then, there was a time when everything started — and usually ended — here in Algiers.

Everything, from the unconditional surrender of an army to the compassionate posting home of an unhappy lance-corporal, had to pass through the usual channels which led from the churned-up mud of an olive grove back 600 miles to a converted bedroom in a stately Edwardian hotel perched on top of a tortuous hill overlooking the superb bay of Algiers.

They used to say that if your wife had a baby it wouldn’t be legitimate until Algiers had given approval.

For two years Allied Force H.Q. showed the world what democratic bureaucracy could do when it went quietly mad.

While generals and admirals toiled over their plans of campaign in bathrooms and pantries, around, above, and below them, 5,000 able-bodied men and women, British and American, struggled and nearly strangled in a vast Laocoön of red tape.

The marvel of it was that anything coherent at all ever came out of that paper maelstrom. But it invariably did.

Your promotion from lieutenant to temporary captain might be held up for six months. But you really had no need to worry.

Somewhere in a tent or a Nissen hut among 100 others sprawling under the trim tamarisk trees of the Hotel St. George there was a deputy director of something or other, complete with a brace of staff captains and a dozen clerks to take care of you.

Your promotion would eventually come through, even if you had got yourself killed and decently buried in the meantime.

In those later days Algiers was really two cities — three, if you counted the squalid square mile of the native quarter which goes under the glamorous name of the Casbah, and was stringently marked out of bounds and off limits to British and American troops.

There was the Algiers of the Allied Officers’ Club in the modern magnificence of the Aletti Hotel.

There was the Anglo-Saxon Algiers with its canteens and gift shops and American Red Cross cinemas and ENSA hostels and British officers’ tea rooms (where for a shilling you got a vicarage tea party complete with string quartette that apparently knew nothing else but Mozart and Hermann Finck).

Some unknown, but accurate, American war correspondent christened it caustically “The Silver Foxhole.” And the name stuck. Life here was about as personal as a railway waiting room.

And there was the other Algiers — an unhappy occupied city of silent bitter Frenchmen in uniform, who hated each other almost as much as they hated their common enemy the Boche.

But it was not always like this. Gliding down on it out of the bright, harsh moonlight of an African night you see it — as those first paratroopers must have seen it — a lovely, snow-white city straight out of the Arabian Nights period.

Then all too soon you are bumping and bouncing and slithering over the metal airstrip the Americans put down at Maison Blanche.

And reality is there waiting for you the moment you step off the plane — reality this time in the form of mud.

Guidebooks rhapsodising about Algiers never mention the mud that follows the Autumn rains.

I can’t think why. For Algerian mud sticks like glue and looks like curdled pea soup.

In that respect only it differs from Tunisian mud, which looks like raspberry jam.

Compared to what it was in wartime, Maison Blanche is a deserted ghost town these days.

But again there was a time when it was the busiest and most important airfield in the world.

Every minute of the day and night saw a plane dropping in from Washington or London or Teheran, refuelling, and taking off again just as casually for Bombay or Reykjavik.

You would stretch yourself out wearily on the bare board floor, your head pillowed on your kit bag, and dose fitfully until somebody called your name and rank.

And then two days later you’d wake up in Chunking with the pink Tunisian mud still on your boots.

Sometimes as you kicked your heels in the dust of Maison Blanche you would curse the mysterious forces called “priorities” which ruled your life.

But some good came out of it after all. For at Maison Blanche was born that magnificent Anglo-American organisation later to be known as Mediterranean Air Transport Service.

It was here — though we little guessed it at the time — that was conceived the strategy of airlift.

And if you take it all back to its earliest beginnings we owe it all to the dozen or so Spitfire pilots who snatched the airfield from under the noses of its Vichy French defenders in the early hours of Friday, November 8, 1942.

They were celebrating the seventh anniversary of the “Debarquement” this morning.

Flags were flying around the war memorial in the Avenue Pasteur. There were “manifestations” outside the Grande Poste, which still remains the handsomest post office in the world.

But you sense that this show of patriotics was merely a polite formality. For Algerians have other more pressing matters to think about just now — the rising spirit of Arab nationalism for one thing, a serious state of affairs in a country where only one in nine is a European.

Four years ago the French authorities put down an Arab insurrection with a harshness that recalls eighteenth-century Ireland.

Now Arab extremists, working underground and as well organised as any European resistance movement, are biding their time.

They believe they have a powerful ally in Moscow. And it is significant that one of the leading Algerian newspapers “Alger Republicain,” which succeeded the proscribed “Depeche Algerienne,” has many intelligent young Moslems on its editorial staff and is frankly Communist in its sympathies.

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024