The ’59 Trail,

Unknown artist – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Final part of my uncle, John Alldridge’s 1959 report from Canada’s Far North for the Birmingham Mail – Jerry F

Whitehorse, Yukon Territory

My problem now was to get out of Alaska and back into Canada. Not as easy as it sounds, with a wall of mountains barring the way.

I had two alternatives. I could go by railway: twelve hours’ journey from Anchorage to Fairbanks, pick up the Alaska Highway there and snake down that eternal switchback for six hundred jolting miles to Whitehorse in the Yukon. Or I could do the whole trip by air, changing planes at Fairbanks.

I took the easy way out. I went by air; strapped in all the way, and shutting my eyes each time we hit one of those infernal air pockets that seem to lie in wait for you like so many whirlpools all around Mount McKinley.

In its rip-roaring, gold-rush days Fairbanks was reputed to be the hottest town south of Nome. And that, with the thermometer frozen at 50 below.

Nowadays Fairbanks has gone heavily respectable. The few surviving log cabins and “false-front” stores are being pulled down. And the Elks, the Eagles, the Rebekahs and the Oddfellows meet here in the same style as they would in Seattle.

A portion of downtown Fairbanks, Alaska in 1960 or 1961,

Lathrop High School – Public domain

There are square-dancing clubs and home-makers’ cubs, and a club for those who would be slimmer. There is a Fairbanks Little Theatre now. And Alcoholics Anonymous.

There are a vast number of bars and saloons with enticing names like the Golden Nugget and the Silver Dollar. They look inviting; until you grope your way into the semi-darkness and find the tall stools at the mahogany bars occupied by teenage soldiers drinking iced beer.

The Fairbanks old-timers were so tough they would have made Dangerous Dan Macgrew seem downright effeminate. There was a fabulous local character called Swiss Jim who once killed a six-foot grizzly with his bare hands.

Now the few old-timers who are left spend their evenings in the lobby of the Nordale Hotel watching Wyatt Earp and Mat Dillon on television.

There is still plenty of gold around Fairbanks. In fact almost every pan of gravel taken from any creek or gulch or river bar will yield “colours.”

The trick nowadays is to make it pay. The U.S. Treasury buys it — and promptly puts it straight back in the ground again at Fort Knox — but the profits are so small they’re almost invisible.

But Fairbanks doesn’t have to worry about a slump in gold. It has the Army on its doorstep. And it is journey’s end on the Alaska Highway, that fantastic road which runs all the way north and north-west from Edmonton, a clear 1,600 miles of it.

So Fairbanks, the last city on the American continent south of the Arctic Circle, is now right on the tourist map.

The souvenir shops do a roaring trade in miniature sacks of genuine “sourdough” flour, gold-nugget earrings, Indian beadwork (made in Hong Kong) and Eskimo ivory carvings (made in Japan).

There are half-day trips that take you panning for gold. And you can fly over the Arctic Circle, 160 miles north of here, and be photographed receiving your Arctic Circle Certificate, wearing a gay, fur-trimmed parka specially provided for the purpose.

Not having much interest in such novelties, I caught the first plane out. Secure at 12,000 feet, I sipped pineapple juice and listened to music from Hawaii. Down below there were snow-capped peaks and ice-blue glaciers where mastodons once roamed—and have left their tusks behind as proof.

And so right down the winding, twisting, 2,000-mile-long Yukon River to Whitehorse.

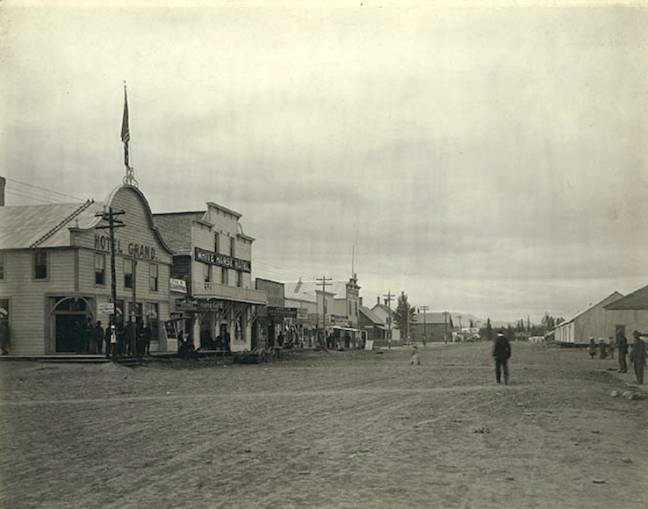

Street in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, ca. 1900.,

Wilhelm Hester Collection – Public domain

Sixty years ago Whitehorse was the halfway mark on the Trail of ’98. It is the railhead for the White Pass and Yukon route, one of the most remarkable railways in the world; 110 miles long and built in two years, largely by gold-seekers who had run out of money.

They worked for a week or two, drew their pay and rushed back to join the mad stampede up the Yukon River to the Eldorado of Dawson City, 146 miles away.

Today Whitehorse is a modern city with a rising population of 5,000. But there is still enough left to show what a rugged man’s town this must have been not so very long ago.

I put up at the Regina, a pleasant little hotel on the waterfront, kept by Swedes who have managed it since it was built in 1900.

I looked out of my window first thing in the morning and got the shock of my life. A fleet of old, tall-funnelled, stern-wheel paddle boats seemed to be steaming majestically up the street.

I looked closer and saw that they weren’t on the river at all. Some of them haven’t felt water under them for ten years.

The Yukon River is a vast graveyard of these old steamboats.

They were usually built in Seattle, shipped to the mouth of the river and then proceeded under their own steam the whole 1,600 miles to the Klondike. But a few smaller vessels were trundled in pieces over the mountains.

The little A. J. Goddard was the first to reach Dawson City from the upper river. Captain Goddard and his wife — she held a first mate’s ticket — packed the boat in sections over the Chilkoot Pass, assembled her on Lake Bannett and ran her through the dreaded Miles Canyon and Whitehorse Rapids, which have been absorbed into a hydroelectric power scheme.

The boats carried 100 first-class passengers and about 300 tons of freight on a draught of four feet and were incredibly shallow.

They were driven by a huge paddle-wheel in the stern, steamed at about 15 knots, and

were able to back up to avoid rocks and sand bars by suddenly reversing the paddle-wheel, a manoeuvre which needed perfect understanding between captain, pilot, and engineer.

The most famous of all these famous stern-wheelers was probably the Yukoner, which was only broken up last year. Her first captain was John Irving, one of the best steamboatmen in the North-West.

Irving was a man of fixed eccentricities. He always had a large oil painting of a bulldog in the lounge, kept a stuffed golden eagle in the pilot house, and employed a giant negro body servant who never left his side.

He had a highly original method of steering his boat. His system was to charge the bank or dock at full speed ahead, his whistle blaring. At the last possible moment he would ring for full astern and the vessel would shudder to a stop in the nick of time — while his passengers dragged themselves to the saloon bar to calm frayed nerves.

On her maiden voyage in the summer of 1898 the Yukoner puffed up the river for Dawson City crowded with dance-hall girls, musicians and gamblers, and loaded to the plimsol line with champagne.

Every time the boat stopped to take on wood for the boilers Irving would call the musicians out on deck to play and the girls to dance while he charged the bank. Then the wood-choppers would be invited on board for champagne cocktails.

Irving only made that one trip up to Dawson. Maybe, an artist, he felt he could never better it. On the return to St. Michael he sold out and left, taking with him his bulldog painting, his stuffed eagle and his negro body servant…

What sort of men were these and what days they lived in you can see — as the Queen will this month — by visiting Whitehorse’s MacBride Museum, a treasure house of gold-rush memories.

This must be the only museum in the world which can show you the remains of a pair of boots cooked for breakfast by a bishop.

The bishop was Dr Stringer, Bishop of the Yukon. In 1909, on a tour of his scattered diocese, he was marooned for several days in a blizzard. All rations gone, he was reduced to boiling his boots.

“Bishop who ate his shoes”,

Library of Congress – Public domain

His comments in his diary are brief and to the point: “October 31, 1909 — Breakfast of sealskin boots, soles and uppers boiled and toasted. Soles better than uppers …”

Reproduced with permission

© 2023 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023