Another chapter from “Special Assignment” by my uncle John Alldridge

(published in 1960 and now long out of print)

When people think of the crime reporter they associate him inevitably with the hurly-burly of Fleet Street and the glossy glamour of London’s nightlife.

But the crime stories that make the headlines every day have no geographical barrier. They are just as likely to happen in some grimy back-street of a Lancashire cotton town as under the winking neon signs of London’s West End.

National newspapers, with an eye on circulation, are well aware of this. In Manchester, where the Northern editions are printed, most of them employ a crime reporter whose roving beat is the whole of the North of England – and a hectic round it can be at times.

Bill Dickson, of the Daily Mail, is typical of these Northern crime-men. In his six years as a crime reporter in Manchester he has had the successes and the failures, the elations and the frustrations that all crime reporters know only too well.

No copyright claimed

The thirty-year-old Scot will have you believe he is still very much a ‘new boy’ compared with his Fleet Street colleagues. New boy or not, his crime beat has taken him on some odd and tricky assignments in his search for the story behind the story.

He has had to tackle the bewildering assortment of crime stories that reporters like Bill can expect any time of the day or night – cases ranging from the macabre murder and complicated fraud to the hazard of gangsterism in big cities. It has meant, of course, working very often round the clock, endless door-knocking and a haphazard home life.

The reward? For Bill, as with all reporters, there is only one – the satisfaction of seeing the results of his work in print next morning.

One story that gave Bill perhaps most satisfaction began, as many of his stories begin, with a phone call one day from a contact. The contact told him that an elderly taxi driver had been robbed, bound and gagged, and hurled out of his cab to spend the night on a lonely golf course.

The driver was in his seventies and Bill didn’t have to be told that a first-hand account of the old man’s ordeal would be front-page copy.

Bill wasted no time. In minutes he was driving, with a cameraman, to the cabbie’s home, where he was recovering after the attack. But Bill’s enthusiasm waned when the door was opened. Standing there was a tall gentleman with the unmistakable stamp of detective all over him.

The C.I.D. man was polite, but firm. “Sorry,” he said, closing the door. “We are interviewing the driver and any publicity would ruin our inquiries.” Despite Bill’s protests the door was slammed in his face.

No crime man, however, gives up so easily. To Bill closed doors are nothing new. In the hope of getting any scrap of information he talked to neighbours, to other taxi drivers, to the hospital where the injured man had been treated.

But it was the same frustrating answer everywhere he went: “Sorry, the police have told us to say nothing.”

Dismayed, and a little anxious about his edition time, Bill did the only thing left to him. He settled down in his car at the end of the street to wait for the detective to leave the house.

The minutes ticked by, then suddenly the door opened and the detective strode down the path. Bill gave him time to get clear, then went to the house a second time to tackle the cabby.

The same uneasy reception was waiting for him. The driver and his family said they had been told by the police to say nothing in case it hindered inquiries.

Bill says he never talked faster in his life, but his insistence paid dividends. He eventually convinced the driver that publicity, rather than spoil things, could help to bring forward people who might have valuable information.

To cut Bill’s story short, the old man did talk and his exclusive story, with pictures, made a splash on the front page – with only minutes to spare.

Next morning Bill had mixed feelings. He was happy, of course, about getting away with a good story. No other paper had a line. But he was just a little despondent about having crossed swords with the police to get it.

Suddenly the phone rang on his desk. He picked it up and heard some news that made his day.

He was told that a man, carrying a copy of the newspaper, had walked into police headquarters – and confessed to his part in the attack. He told the startled policeman that he was giving himself up only after reading Bill’s story and realising what a serious crime he had been involved in.

So, although every barrier had been put in his way, Bill had got the story – and in doing so had also got his man. At the trial later, when the man was convicted and sent to prison, the newspaper carrying the story was put in, as evidence. Bill doesn’t mind admitting that he got a kick from the fact that his story, far from ruining inquiries, had done the very opposite.

Some days later Bill met the detective who had turned him away on the cabby’s doorstep. They shook hands and decided to forget their ‘little misunderstanding’.

Bill, of course, would never have had that story but for a tip from a contact. Over the years Bill has built up personal friendships among policeman, among the criminals and among those shady people on the fringe.

Says Bill: “The contact is the backbone of every crime reporter. You just couldn’t earn your bread and butter without them.”

His daily routine, as with all crime reporters, is to keep in close touch with his contacts day and night. It means a heavy intrusion into what few leisure hours he has – but then there are few places in national newspapers for people with the nine-to-five mentality.

Are contacts the only source of Bill’s information? Not quite, he says.

Police forces have progressed from the bad old days when cooperation with the press was taboo. Today many enlightened forces in the provinces have a senior officer whose job it is to deal with press inquiries. In a really big story, say a murder, press conferences are usually held to keep newspapermen up to date with developments.

The reason for this cooperation is a matter of common sense. Policemen know that, in these days of mass circulation, newspapers go into millions of homes – far more than the patient detective is able to reach. Time and again published details of a crime have jogged the memory of people who have been able to give police vital information – all because of newspaper publicity.

But Bill, like his colleagues in crime reporting, regards the official police hand-out as merely the appetiser. For the real meat of any story he depends on contacts.

Of course, having contacts who are really in the know can be embarrassing, too – as Bill knows to his cost.

Some time ago a detective friend rang Bill and told him he would find a good story if he went to a certain address. The detective said he could tell him no more, and rang off abruptly.

It was all very mysterious, but luckily Bill recognised the address as the home of a Mr X who had been in trouble with the police more than once.

Bill drove out to the house and was surprised to find the street tranquillity itself. Hesitantly, he knocked at the door, not quite knowing what to expect. To his surprise, Mr X himself answered the knock.

“Hello Bill,” he said, recognising Bill from previous meetings in court. “What brings you here?” Bill went inside and then followed what Bill describes as the most uncomfortable half-hour of his life.

Says Bill: “It took only a few minutes of general conversation for me to realise that if there was a story around, Mr X was genuinely unaware of it.

“I knew my contact was reliable and that anything could happen at any moment. Yet I couldn’t risk arousing the suspicions of Mr X. It meant that for half an hour I had to chat away about everything under the sun – and try to be casual at the same time.”

“But it was obvious after a time that Mr X was very suspicious about why I was there at all. I tried to pass off my visit as a social call and told him I ‘just happened to be passing’. The doubt, however, was still very much on his face when I managed to mumble some excuse and left the house.”

Bill stood outside the house, frankly baffled about what was going on. What to do next? He shrugged his shoulders and decided to drive back to the office convinced that his contact must have got his information a bit garbled.

What a fool he was! Within minutes of his driving away, two car-loads of detectives screeched up outside the house. The C.I.D. men piled out and almost turned the house upside-down, looking for arms and ammunition which they had been told was hidden there.

And Bill, on his way back to the office, didn’t know a thing about the raid until next morning.

What happened was that Bill had first driven into the street just seconds before the detectives arrived. They saw him going up the path and decided to pull their cars round the corner and delay the raid until he had left the house. The trick that Bill played on the taxi-driver story had rebounded on him! So he missed a good story simply because his information was just that bit too much in advance. Said Bill: “I felt a bit of a fool when I told the boys about it next day. And I told my contact that although I like early tip-offs I didn’t like them so early.”

These, of course, are the ups-and-downs of crime reporting to which the newspaperman becomes hardened over the years. But he can never be complacent about the story he has missed and shrug it off as ‘one of those things’.

The newspaper business is highly competitive and news editors want reporters with the reputation of being able to get the story, no matter what the difficulties. It breeds an intense, but friendly, rivalry between the crime men of competing newspapers.

What about the personal hazards of spending your life writing about gangsters and murderers, petty thieves and glib confidence men? The hazards are neither as many, nor as macabre as the Hollywood films might have you believe. But Bill, like his colleagues, feels now and again there must be an easier way of making a living.

The biggest scare Bill got was one winter night when he was trying to trace the movements of a London gangster who had made a sudden trip to the North.

Bill’s information was that there was something very sinister behind his trip, but even Bill’s normally talkative contacts could tell him nothing.

It was a case of starting right from the beginning. Bill visited a few of the nightspots in Manchester until, with luck, he found out the names of two of the gangster’s associates in the city. Then he set out to find them, hoping they would know something to put him on the track of the Londoner.

But in the bars and nightclubs of Manchester all his inquiries were met with blank stares. No one, it seemed, knew of the two men he was looking for.

Several hours later Bill called at his umpteenth club that night. Within minutes of ordering a drink he sensed an uneasy atmosphere. Almost before he had had time to inquire about the two men a waiter hurried over to him and suggested he should leave because “no one here knows anything”.

Bill was puzzled, but he had no option but to drink up and walk out. He didn’t bargain for what happened next.

He had just walked away from the bright lights of the club when he heard quick footsteps behind him. Before he had time to turn round a violent shove in the back sent him reeling into a dark doorway.

Bill admits: “Believe me, I’ve never been so frightened. Two men grabbed me by either arm and when I managed to peer up at their faces I realised I had seen them drinking in the club a few minutes earlier.”

“One of them wanted to know ‘which mob I was from’ but it was the other man who was really worrying me. He looked as though he wanted to get the beating-up over within the shortest possible time.”

Bill had to talk – and talk fast. His protests that he was a newspaperman were sneered at until Bill pulled out his press card which, like every reporter’s, carried a photograph.

That did the trick. The men quietened down and let Bill talk.

It turned out that these were the very men Bill had been looking for all night. Earlier in the evening they had overheard Bill asking for them in a bar. Curious, they followed him to the club to see if they could discover what Bill’s interest in them was.

Anyway, the night turned out well because once they knew who Bill was they gave him some first-class information about the movements that day of the London gangster. “But,” said Bill, “it wasn’t an experience I would relish again.”

You might wonder why waiters and barmen had told Bill they hadn’t seen the two men when all the time they were in the club, just a few yards away?

There, Bill was up against a problem that the police are facing every day – the natural reluctance of people to get involved in any inquiry. Fear of reprisal by gangsters leads many people to tell police they know nothing, when in fact they could give valuable information.

Don’t think, however, that every personal hazard to the crime reporter must come from the criminal. One evening three housewives managed to scare Bill more than a bunch of thugs would have done.

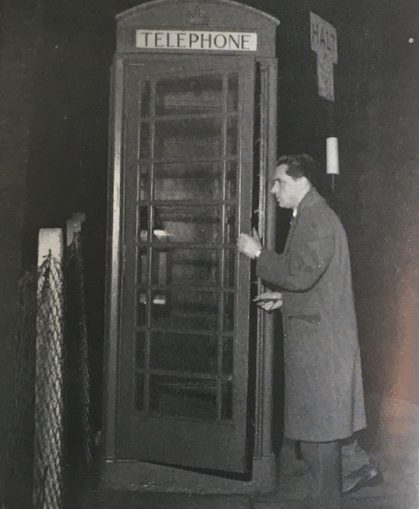

Bill was in Wigan, reporting the second murder there in nine months. He had been in a telephone box for about fifteen minutes dictating his story to the office when suddenly he was almost deafened by a loud rat-tat-tat.

Bill turned around and saw three very angry women hammering on the glass partition with pennies. Tired of waiting to use the phone they had decided to try to terrorise Bill out of the box by beating a tattoo on the windows.

They kept it up unceasingly. Bill realised they meant business, hung up the phone and frankly admits he ran for his life.

Said Bill: “When I saw the look in those women’s eyes I knew I had never been closer to a lynching. But I don’t think my news editor appreciated why I had to phone the other half of my story from another box sometime later.”

So remember, if you see a rather harassed man in a phone box with some scribbled shorthand notes in front of him, not to be too hard on the fellow. The chances are that he’s a reporter – desperately trying to catch his edition.

Note:

Bill Dickson retired from journalism in 1991. He died at the age of 82 in 2011, initially thought to be as a result of deliberate contamination of saline drips with insulin at Stepping Hill Hospital in Stockport, Greater Manchester.

See: 2011 Stepping Hill Hospital poisoning incident, Wiki

Jerry F 2022