Internet Archive Book Images, Public domain

If one were of a particularly cynical nature, one might think that a piece with this title might have been written to comment upon the near unbelievable social and political culture we find ourselves living in in 2023.

But no, neither my blood pressure nor sanity would stand for that. I shall leave that thorny topic to Puffins much more knowledgeable than I, with a better understanding of the nonsense we’re surrounded by, both in its history and its implications for our futures.

Instead, I will explore something much more down to earth and enjoyable. No, for those musically minded, it isn’t anything to do with Eva Peron and the delectable David Essex in ‘Evita’ either.

This will take us on a wander through the origins of something that the Collins English Dictionary describes as “…a group that consists of clowns, acrobats, and animals which travels around to different places and performs shows.”

Yes, the Circus is coming to town!

So… Roll up! Roll up! Come one, come all. Hurry to take your ringside seats for the most excellent, the biggest, the best, the greatest show on Earth. Thrill to the most tremendous acts of all time. Witness the wondrous antics of our esteemed equestrian entertainers, tremble at rope dancers intrepidly treading the tightrope, chortle at our clowns’ comical capers, gaze in awe at our acrobats’ antics, marvel at our mystifying magician, and wonder at the fabulous feats of our strongest of strongmen.

What we now know as the circus has relatively modern beginnings, although elements of it date back a long time. It has been said that this popular spectacle has its roots in ancient Rome. In fact, that it might stem from the not entirely family friendly gladiatorial contests staged at Roman amphitheatres.

An amphitheatre was typically an open-air, oval, or circular building, with tiered seating. They may have started as wooden structures but became well-established as permanent fixtures constructed from stone, across the Empire. They were almost ubiquitous, so found in many Roman towns and cities. Indeed, in the relative backwaters of what was the Roman Province of Britannia, the remains of fourteen amphitheatres can be found in England alone, with a further four in Wales, and two in Scotland.

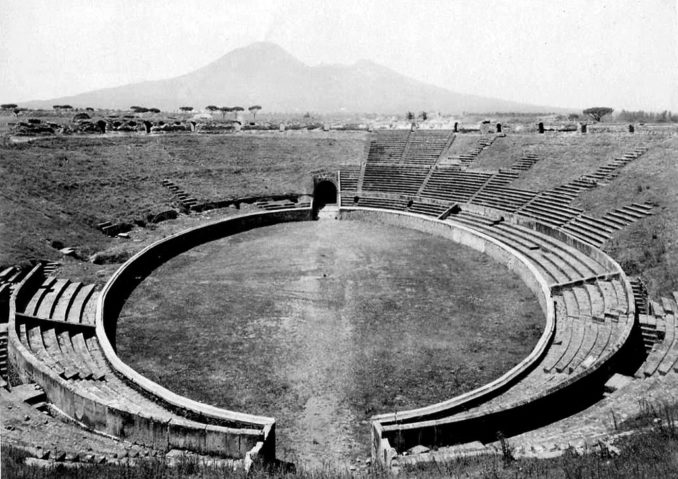

The earliest amphitheatres appear to have been built around the end of the second century BC, with the oldest surviving example being the Amphitheatre of Pompeii, seen below in the 1800s, with what appears to be Mount Vesuvius gently smoking in the background. It was this amphitheatre in which the 1972 filmed concert ‘Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii’ was staged.

Giacomo Brogi, Public Domain

At the height of the Empire, many amphitheatres would comfortably seat (er, on stone benches ‘comfortable’ isn’t necessarily the word I’d use) between forty-thousand and sixty-thousand people. The largest of them, like Rome’s Colosseum, the biggest amphitheatre ever built, could accommodate up to a hundred thousand at a stretch, though it usually entertained considerably fewer. That’s a lot of bums on seats!

Interestingly, although we have taken the name ‘circus’ for the venues we know today, a Roman circus was actually a little different. Largely constructed between, 200 BC and 200 AD, again, they were large open-air venues, but they were not circular. In plan, the circuses were rectangular with a half-circle at one end, to give two long race track ‘straights’, divided by a central ‘spina’, with a curve at one end and the slanted starting gate (the ‘carceres‘) at the other. Only one example is known from England. Sections of this 1,476-foot structure can be found at Camulodunum (now Colchester) the first capital of the province of Britannia.

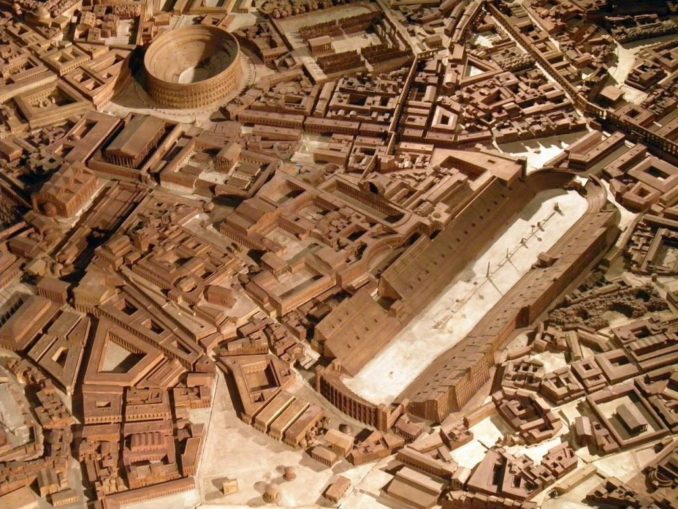

Circuses were used primarily for public games celebrating a number of religious festivals in the Roman calendar. At other times, horse or chariot races were staged at these huge venues (sorry, but I simply cannot resist a reference to the instantly recognisable and iconic chariot race in Ben Hur), but public executions, plays, and staged animal hunts were also common. The circuses were often larger than amphitheatres, with Rome’s Circus Maximus able, at one point in its history, to seat an audience of a quarter of a million people.

A scale model of Rome in the 4th century shows both the Colosseum (in the upper left quadrant), and the Circus Maximus (bottom right), giving a good idea of the differences in scale.

Pascal Radigue, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

But what of the more modern circus? Well, although he didn’t invent this concept, the circus we now know, and love, comes from a man who was the son of a town quite close to where I am today.

His name is Philip Astley, and he was born on January 8th, 1742, in Ladd Lane (now renamed Astley Walk in his honour) at the heart of the Staffordshire town of Newcastle-under-Lyme, once an important staging post on the road to London. Incidentally, this year, the town is celebrating the 850th anniversary of its first charter, granted by King Henry II in 1173, which saw the town acquire the status of a borough.

Philip’s father was Edward Astley, a reputable cabinet maker and veneer-cutter. As a boy, Philip received little or no education but apprenticed with his father at nine years of age. Like his sire, he was known to have a short fuse and a passion for horses (as a lad, Philip indulged this love by helping out with stabling the stagecoach horses which passed through his town). But unlike his father, Philip’s future lay not in wood. He would make his mark with his beloved horses.

In 1759, aged just seventeen, his hot head butted up against his father’s one time too many. So, he left home (by now in London, as the family had moved from Newcastle-under-Lyme when Philip was 15) to enlist in ‘Elliot’s Light Horse’ under Colonel George Augustus Eliot, 1st Baron Heathfield. At that point recruiting officers were offering young men the King’s Shilling to join the new regiment. In reality this regiment (later known as the 1st Light Horse) was the 15th Light Dragoons. This was the first Light Cavalry Regiment of the British Army, one which Eliot had been entrusted to raise during the Seven Years’ War.

Part of the new recruits’ initial training was to learn ‘trick’ riding. The consensus at that time was that ‘the best horseman will always win against the best swordsman’. Philip excelled in this, rapidly coming to the attention of his instructor. This was the legendary fencing and riding master Domenico Angelo, horse trainer to Lord Pembroke, who conducted this initial training at Wilton House, near Salisbury. He identified Philip as an audacious, decisive, and quick-thinking rider. He went on to prove to be an excellent cavalryman, later rising to the rank of Sergeant Major.

He was rightly admired as a war hero, not least for his part in the 1760 Battle of Emsdorf, which was largely won by his regiment, despite their suffering heavy losses. Their opposition, the French forces led by Marechal de Camp Glaubitz, lost almost a hundred and eighty officers, and a further two and a half thousand soldiers were taken as prisoners of war. In addition, six guns and sixteen infantry colours were taken, one captured by Philip himself.

Yet more heroic, he proved his bravery without doubt, by riding through French lines without assistance to rescue the Anglo-Hanoverian forces’ commander, German-Prussian field marshal Duke Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Whist not singling out Philip, Ferdinand, the Duke of Brunswick commented in dispatches that:

“His Serene Highness, therefore, gives his best thanks to these brave troops, and particularly to Eliott’s regiment, which was allowed, by everybody present, to have done wonders.”

Henceforth, the 15th Light Dragoons were entitled to display the title ‘Emsdorf’ on their helmets, the first Battle Honour ever awarded to a regiment.

Perhaps this formative experience at just eighteen years old matured Philip. It certainly cemented the fact that he was a superbly innate horseman. Indeed, he was so well regarded in this respect that he was placed in charge of breaking in any new horses for his regiment.

He seems to have had a natural affinity with horses, to the point where he might be almost considered an 18th century ‘horse whisperer’. Every horse he took on had an introductory session with him alone, free from any distractions, to gain their trust. If interrupted, the lesson would be shelved for that day and repeated from scratch on the next. Once satisfied, Philip then took care to introduce the new horse to experienced steeds, to learn from them. He was a firm believer in rewards like a slice of apple to reinforce expected behaviour.

This was a far cry from the ‘breaking’ that was prevalent at that time, and may have contributed to his success, particularly as one aspect of training new cavalry mounts was to make sure the horses were acclimatised to unexpected noises. It was, after all, imperative that the mounts didn’t take fright at the sound of gun shot, rearing to unseat their riders in the heat of battle.

Throughout his service Philip was able to observe and learn from a number of professional trainers and riders. Thus, Philip honed his equestrian skills yet further, to become an excellent trainer, and an even more accomplished trick rider. This stood him in good stead for his next adventure.

After leaving the regiment in June of 1766, he married a lass called Patty Jones (another talented rider) and, in May of 1767, Philip and Patty had a son, John Philip Conway Astley. Around this time, trick riding exhibitions, often in the Cossack style, were extremely popular in Britain. Philip’s superb horsemanship fitted this fashion like a glove, so he and Patty toured the country giving equestrian demonstrations and displays of trick-riding for about two years until, judging themselves ready for the discerning audiences of the capital, they settled in London establishing Astley’s Riding School in 1768.

Always a towering lad, by now, Philip was a truly imposing figure. At over six feet in height, he stood head and shoulders above many of his countrymen, and his time in the military as a Sergeant Major meant he had developed a thunderingly powerful voice. He was not a man to be easily overlooked, larger-than-life with the confidence and personality to match his physique.

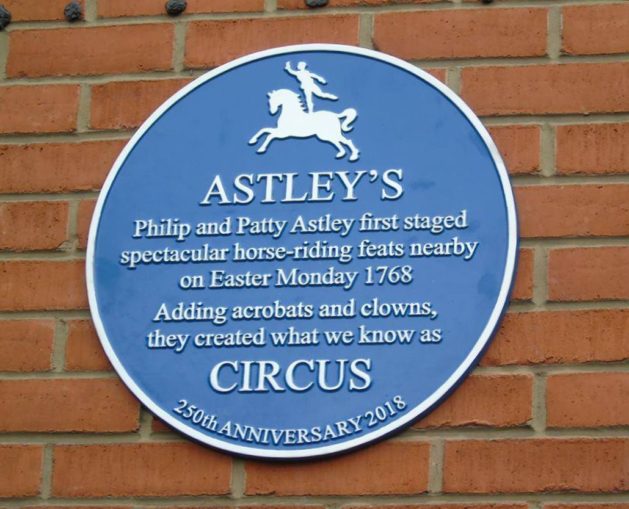

The Astleys set up their fledgling business on a scrap of land at Ha’penny Hatch, in an area sometimes described as Lambeth, though it seems to have been behind St John’s Church, in Waterloo. A Blue Plaque now marks the spot, at the junction of Roupell Street and Cornwall Road.

Chris Barltrop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Upon his discharge Philip had been presented, by General Elliot, with a white charger, a ‘Spanish Horse’, called Gibraltar. Philip had taught his beloved Gibraltar a number of tricks, playing dead, and even how to add and subtract. He had bought another horse in Smithfield, and these two formed the basis of the Astley equestrian troupe.

An enterprising couple, in the mornings, Philip and Patty taught horsemanship, and, in the afternoons, they put on a bit of a show, demonstrating acrobatic riding, and performing a variety of equestrian tricks to passers-by on the busy footpath.

He constructed his first ring (which he called ‘the ride’) with a rope and stakes and went round with his hat after each performance to collect whatever generosity his audience had to offer. Philip was an innate and larger-than-life showman so acted as the ringmaster as well as performing a number of tricks, like riding multiple horses at once. Gradually, he began to build an impressive standing.

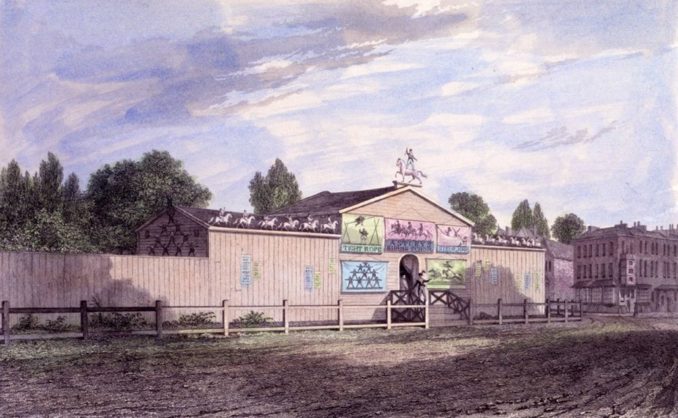

The land at Ha’penny Hatch was marshy though, and the summer of 1768 was a wet one. Not ideal for the sort of entertainment Philip and Patty had to offer. Luckily, they were able to get another piece of land, on an old timber yard near Westminster Bridge, to build a more permanent base, where Philip constructed a ‘grandstand’ of wooden seating. There’s sadly no trace left, but this stood at 225 Westminster Bridge Road, and a flagstone set into the garden of St Thomas’s Hospital, Lambeth, commemorates its original location.

Engraving by Charles John Smith (1808–38) after William Capon, Public Domain

As his prosperity grew, the original modest structure became ‘Astley’s Amphitheatre of Equestrian Arts’. Slowly, he began to include other types of performers to fill in the pauses between the equestrian acts. By 1770, these acts included acrobats, performing dogs, tightrope walkers, jugglers, and clowns. He also introduced musical accompaniment for the acts and in the intervals between. This was the first time such a variety of acts was brought together in a single show.

With this, albeit rather unwittingly, Philip Astley, the local lad from Newcastle-under-Lyme, had become the ‘Father of the Modern Circus’.

Although the audience (or some of them) were under cover, the performers were still exposed to the elements. Given the vagaries of the British weather this was an improvement, but still not ideal. More shelter was definitely needed, but timbers were not cheap to buy.

So, demonstrating his keen business sense, and canny entrepreneurship, Philip soon saw an opportunity which was too good to pass by. In 1772 he bought up previously used timber that had been part of scaffolding erected for the funeral of Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess Dowager of Wales. His woodworking expertise soon licked this into the shape he required, and covered seating meant larger audiences.

Then, biding his time for the best ‘deal’, a few years on, he spotted one. After the General Election which returned Lord North (a fledgling ‘tory’) to power, he noticed that a considerable amount of timber which made up the hustings (where the various political campaign speeches had been made) would be there for the taking.

At that time, it was customary for the public (whether in absolute delight, or sheer disgust) to turn the wooden hustings into bonfires as the elections closed, but Philip had a cunning plan. He made it known that, if the wood, instead of being burned, was to be transported to his Amphitheatre, the carriers would be rewarded with free beer!

This plan worked like a dream, and Philip was able to accumulate enough wood to entirely cover and modernise his existing buildings. Not only that, but it enabled him to build two tiers of seating with a gallery, a stage, and an ‘orchestra’ pit, and cover the whole of the performance area with a domed roof (those cabinet-making skills he developed as a child really had come in handy after all).

At first, being accustomed to watching entertainment in the open air, this was not at all well received. Never one to give up, Philip simply decorated the interior with trompe l’oeil paintings to depict the sky with trees. But Philip’s sharp business acumen meant that he was well aware that being under cover would not only protect his performers but allow him to stage performances by candlelight. Losing the daylight was no longer an obstacle. More bums, on more seats, for longer. He really was a genius.

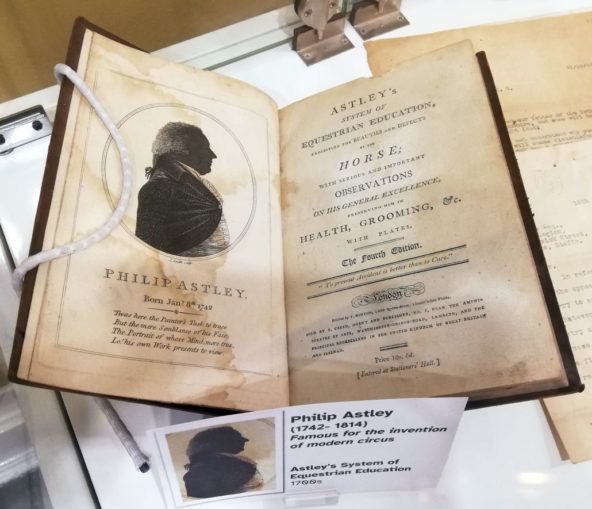

He was also keen to pass on his skills with horses, and in 1775 he published a book, ‘The Modern Riding Master’. In the years following this, he expanded upon his work, republishing it as ‘Astley’s System of Equestrian Education’.

SharpieType301, 2023

There’s a slightly battered copy on display in The Brampton Museum in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Philip’s hometown.

As we have seen, the Amphitheatre was a wooden structure, and on a number of occasions it was completely destroyed by fire. Accidents or a jealous rival? Who knows, but on every occasion, Philip built back better (hmmm, now there’s a slogan that sounds familiar). He obviously did something right, as Astley’s Amphitheatre remained on the site on Westminster Bridge Road for almost a hundred and twenty-five years.

He performed for His Majesty King George III and his family, and also took his extremely successful show on tour. The Astley’s troupe visited Dublin, Vienna, Belgrade, and Brussels, firmly establishing him as a successful entrepreneur with a good reputation, which only strengthened when he put on a performance for King Louis XV of France (Louis the Beloved) at Versailles, and later, his successor, the rather less beloved King Louis XVI and his wife Marie-Antoinette.

Little by little, he became more famous and wealthier. As he did so, his business could expand. In fact, he ended up building an additional Amphitheatre in Paris (after enjoying the patronage of King Louis XVI). There is some evidence that Philip built no less than nineteen amphitheatres (by any other name ‘circuses’) in various European capitals.

Whether or not this is true, his setup was certainly mimicked by others, including his former employee and competitor Charles Hughes, who not only introduced the modern circus to Russia, but set up his own ‘Royal Circus’ a mere hop, skip and a jump away from Astley’s amphitheatre, the cheeky devil!

But Philip never forgot his roots, and when war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in the spring of 1793, he willingly assisted Prince Frederick, Duke of York with transporting the cavalry and artillery horses to the Continent, just months prior to the ill-fated siege of Dunkirk.

Furthermore, the troops posted to France included Philip’s old regiment, the 15th Light Dragoons. After his own involvement in the Seven Years War, Philip well knew the deprivations of a campaign and the effect this could have on the men and their morale. So, he gave a gift to the regiment of all the materials the men might need to repair and maintain their footwear, clothing, and equipment. He even enlisted his staff at the Amphitheatre to sew warm waistcoats for each man in the regiment. Better still, he had sewn into a corner of the jerkins a silver shilling, something he referred to as ‘a friend in need’.

This generosity was very well received, and, rightly, well reported. As a consequence, this meant he welcomed in even more audiences to his equestrian entertainments. But although it might sound like a mere publicity stunt, Philip truly meant his support for the men in arms.

However, perhaps Philip’s greatest additional claim to fame was not this, but that his ‘ideal’ sized ring of 42 feet in diameter, which he determined was the best size for galloping horses, became the standard size for a circus ring, even to this day.

As to Philip’s birthplace, the town now remembers and honours its famous son, not just with exhibits in the museum but with a truly unmemorable, ghastly cut steel sculpture next door to a hairdressers’ and outside a slightly shabby looking block of flats on George Street.

Google Street View 2023, Google.com

Ah well, despite this modern abomination, his name will not be forgotten. In ‘Emma’, the novel by Jane Austen, a visit to Astley’s brings a reconciliation between Robert Martin and Harriet Smith, resulting in their engagement. In more modern times, ‘Astley’s’ features in a novel, ‘Burning Bright’ by Tracy Chevalier, where the Kellaway family move from Dorset to the house in Lambeth next door to William Blake and become involved with the circus as run by Philip’s son John.

But the finest tribute to this extraordinary man must go to Charles Dickens, the great English writer and social critic. Dickens not only describes Astley’s Amphitheatre in ‘Master Humphrey’s Clock’ but devotes an entire story in his 1836 ‘Sketches by Boz’ to a visit to the circus. This begins: “There is no place which recalls so strongly our recollections of childhood as Astley’s…”. For those of you who would like to read on, it can be found HERE in its entirety. It really is a beautifully evocative piece.

After forty-six years building up his amphitheatre and performances, entertaining nobility and the common man with equestrian delights, Philip Astley died, at the age of 72. He was in Paris when, on 20 October 1814, he diagnosed with ‘gout of the stomach’. More likely this was a form of stomach cancer, but records are unclear. In any case, he was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery, the largest cemetery in Paris (also the final resting place of Frédéric Chopin, Jim Morrison, Edith Piaf, and Oscar Wilde). His son, John, succeeded him in the business.

I shall finish by pointing you to the man in his own words. OK, it isn’t really Philip, but professional ringmaster Chris Barltrop, who recreates this larger than life character and tells the tale in his place, in ‘Philip Astley – meet the Father of the Modern Circus’.

© SharpieType301 2023