Ninth in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in January 1968 – Jerry F

Nine Quarter Circle Ranch, Gallatin Gate-Way, Montana.

When Howard Kelsey, boss of the Nine Quarter Circle, asked me over supper whether I’d like to go out in the morning with a couple of the boys and round up some stray horses, I thought he was joking.

But up here in this horseman’s country, where rustling is still judged more seriously than murder, you don’t make jokes like that.

Now it must be all of 20 years since I last put a leg across a horse, and that was only on the South Shore at Blackpool.

So it seemed an awful long time before I could manage a carefree grin and a hearty “Sure!”

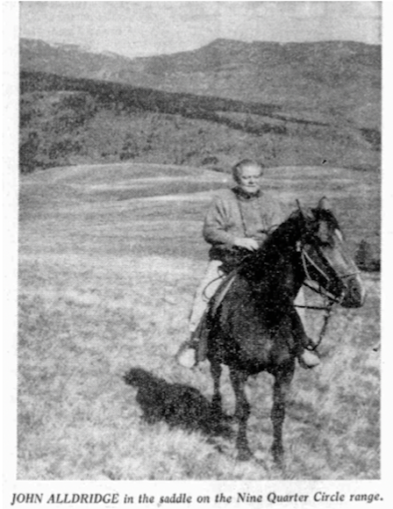

John Alldridge in the saddle on the Nine Quarter Circle range,

© Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board

After which my appetite for that enormous ranch-house meal of prime Montana roast beef — enough meat on that table to keep half a dozen English families happy for three Sunday dinners in a row — was gone. Like many Montana ranchers, Howard Kelsey, a tall, slim, easy-moving man in his 50s who looks like Randolph Scott, used to raise cattle but is now in the dude ranch business.

Happily for him his Nine Quarter Circle ranch was homesteaded as far back as 1892, which means that its 3,100 acres of wooded mountain and rolling grassland on the edge of the Rockies is entirely surrounded by 2,500,000 acres of National Forest.

The nearest town is 65 miles away and the ranch house is five miles from the nearest road.

The ranch house, built of split pine logs, stands on a steep knoll overlooking a wide meadow, through which runs a turbulent stream.

Away from it all may be, but there is nothing primitive about the Nine Quarter Circle.

From his office Howard can talk down guests arriving by plane on his private landing strip.

As Howard’s paying guest you live in a snug log cabin with every modern convenience laid on. You can swim in a heated pool. Your laundry is done by automatic washer and your meals prepared in an all-electric kitchen.

But from then on the Kelsey guests — Howard and his charming Ulster-born wife, Martha, can accommodate 90 at capacity — are on their own.

They have come here to enjoy the simple life. And they certainly get it.

Breakfast is at seven — served on long wooden tables in a mess hall hung with a gallery of Western scenes by that master artist of the West, Charles Russell.

Lunch is at 12. And supper at 6.30. The meals are homely but huge, cooked and served in strictly Western ranch-house style.

For the rest of the day their guests are free to do pretty well what they like.

They can ride on the range under the guidance of expert “wranglers.” They can fish in streams where the fat trout positively swim up and beg to be caught. They can go out on a pack trip into the mountains for days at a time and hunt elk and moose, and bear, and the formidable Rocky Mountain sheep.

But it is horses that have made the reputation of the Nine Quarter Circle. Howard Kelsey has more than 100, sturdy mountain-bred ponies for the most part, that can pick their way through a wood of tightly-packed pine trees as daintily as a ballet dancer.

Kelsey’s pride are his Appaloosas, a rare breed of horse — brown with white polka-dots on face and rump — originally developed by the Nez Perce Indians right here in Montana and once nearly extinct.

A leopard-spotted Appaloosa in Stampede Park,

Seerig, Sergei S. Scurfield – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Thanks to the efforts of men like Howard Kelsey there are now about 2,000 purebreds.

Everybody is expected to ride at the Nine Quarter Circle. If you can’t ride when you arrive, you almost certainly can by the time you leave. You graduate by degrees.

The dude “rides” come in four kinds — the Turtle Trot, for raw beginners; the Cowboy Special, for those who already know their way around a horse; the Dude’s Delight, for those who think they know all about it; and — strictly for experts —the Kelsey Terror, a seven-hour cross-country run which is practically up to Olympic standard.

I used to think that the Western gear worn by dude ranch guests was just so much fancy dress. I’ve found, from painful experience, that it isn’t.

If you are going to ride Western-style, you need, first and foremost, skin-tight Levis that don’t crease or chafe between the thighs in that wide cowboy saddle. You need the sharp Texas boot, its pointed toe designed to fit easy in the broad stirrup.

You need gloves, for your bare hands sweat in the heat, and going through woods the pine tree branches tear them like knives.

Above all you need a wide-brimmed stetson to shade your eyes against the glare of the sun, which at 9,000 feet can be fierce. The problem is how to wear this gear and not look ridiculous. Particularly as all the men around here look like Gary Cooper.

This is somehow appropriate, for this was “Coop’s” country. He was born in Helena, the state capital, went to school at Bozeman, 65 miles down the road, and bought a ranch across the valley, which is still doing nicely.

Once, when he was making a film up here, he lived in the cabin just behind mine. It still bears his name.

Since fodder is expensive at this height and a horse is a hearty eater, Howard lets his animals fend for themselves through the winter.

This means that at the end of each autumn Howard and his wranglers must make a 40-mile trek over the mountains with 100 fretful horses who don’t want to leave the lush meadows.

And then, early in June, they must be rounded up and driven home again.

This is where I came in. For when we arrived at the ranch after a breathtaking drive through Yellowstone National Park we found that all Howard’s horses were in but 12.

And with a new dude season starting on Saturday, every man who could ride was needed to round up the strays.

I spent a somewhat restless night disturbed by dreams of a nightmare Grand National in which I was riding one way round and the rest of the field the other.

After a hearty breakfast — of bacon, eggs done “easy over,” a mountain of hot cakes dripping in butter and maple syrup — I reported to Slim Bitle, the foreman

Slim is quite the slimmest man I have ever seen; he has length without breadth.

He looked at me thoughtfully, then handed me over to Swede, whose real name is

Delyar Grube and who has been dude-ranching for 15 years.

Swede didn’t look too happy about me either, so he called in Big John Wheeler, who is quite as handsome as Rock Hudson, and has taken a degree in motion picture production at Montana State University, and will soon be off to Hollywood to try his luck.

After some pretty high-level discussion, they finally mounted me on Copper, a 20-year-old chestnut gelding, old in the way of dudes, and slow and steady which suited me fine.

After 20 years of it, Copper knows exactly where he’s going, I was quite happy to sit back and leave the driving to him.

Looking back on it now, remembering how saddle-sore and horribly stiff I was, it was an unforgettable experience. I wouldn’t have missed it for all the horseflesh in Montana. But somehow I don’t think I’d care to repeat it.

We rode for three hours cross country, against one of the most beautiful backdrops in the world, the snowcapped Rockies. We picked our way — or rather Copper did —through meadows smelling fragrantly of sage and dappled with orchid, yellow and purple.

There was an exhilarating, dream-like quality about it all. In those three hours, I watched great clouds, like clipper ships, sail down the sky and come to anchor on the mountaintops.

I watched a young family of elk playing in the meadow below. I learned the difficult trick of lighting a cigarette in the saddle.

And I discovered, I think, why men like “Swede” and “Slim” and Howard Kelsey could never leave this Big Sky Country …

And we found our strays. Twelve of them — white, and dapple-brown and coffee colour — sneaking behind a thicket, for all the world like a bunch of juvenile delinquents waiting for their probation officer to catch up with them.

There was only one bad moment. On the way home John decided to take a shortcut through a sloping wood.

I felt myself going downhill at an angle of 45 degrees, leaning desperately back in the saddle through a natural obstacle course of young pines, booby-trapped with razor-sharp branches and fallen timber half-buried in mud.

I don’t think I’ve ever been quite so scared in my life. Until I remembered what Swede had said: “If you get in a jam, let the horse have his head. Don’t panic him, and somehow he’ll get you through.”

And — good old Copper! — that’s exactly what he did.

I’ve ridden the range. And those TV Westerns will never seem the same again …

NEXT: On the rodeo circuit.

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023