In 1954, as the centenary of the end of the Crimean War approached,

my uncle John Alldridge produced a series of articles for the

Manchester Evening News which vividly described that campaign.

In this article, the words are his; the choice of illustrations is mine.

Jerry F

Sebastopol: Army boys thrown into the jaws of death

By the spring of 1855 – a spring long delayed – the war in the Crimea was approaching a stalemate in which victory, one way or the other, lay now with the artillery.

Behind their defences in Sebastopol the Russians, inspired by their brilliant engineer, Totleben, had been as busy as ants all winter throwing up massive strong-points.

Against these fortifications, so strong, so deep, so honeycombed with tunnels that they resembled rabbit warrens rather than man-made defences, the British and French artillery broke and smashed relentlessly, but in vain.

In many ways the shell was the most effective weapon used in the Crimean War: deadly, demoralising, and immensely spectacular.

The burning fuse produced in the daytime a thin whirling spiral of smoke; by night a spluttering trail and eddy of brilliant flame.

For a moment the shell could be seen, hovering in the sky or flickering among the stars; and then, after passing over the crest of its giddy arc, it would rush and howl downwards.

The biggest shells were fired out of stubby mortars; the largest mortar had a 13in bore and the weight of its loaded shell was about 200lb.

“Heroic men,” we are told, “would often lift a shell as it lay on the ground with its fuse roaring off in a jet of sparks and would throw or roll it over the parapet.”

There were a number of ingenious and fiendish variations. The Russians had “Whistling Dick” which could annihilate a couple of men without leaving a trace of them.

There were “bouquets” which burst in the air, showering down small grenades; there were “light balls” – an early form of Verey light – for illuminating the field at night; there was something called a “carcass”, which seems to have been an ancestor of the incendiary bomb of World War II.

Day and night the guns of both sides roared and rumbled. And beneath this blinding, grinding cannonade that rarely ceased the British infantry hung grimly on in its trenches outside Sebastopol – ever on the lookout for sudden sallies from the city.

On the night of March 23 a working party of the Lancashire Fusiliers, revetting an unarmed battery far forward of the British line, was overwhelmed by one of these sudden, silent attacks.

For a time the Russians held the battery. Then the Fusiliers, under Captain Chapman, counter-attacked with the bayonet and threw the Russians out, killing 10 and capturing two.

In June a supreme attempt was made to break the deadlock. June 17 was chosen as an auspicious date – the 40th anniversary of Waterloo. It was a complete and utter failure. Once again each ally attacked independently, without waiting for the other.

Raglan’s men – many of them boys straight out from home, carrying rifles they had never been taught to fire – went forward in confusion from the start. They were packed three deep in the trenches along the start-line and clambered over the parapet in a sprawling, dislocated mass.

A few minutes later they were racing hack towards those same trenches, trampling on the screaming mass of wounded already lying there.

Raglan never got over the shame of that disaster. Only a few days after it – on June 26 – he died, officially of cholera, unofficially of a broken heart.

Pictorial history of the Russian war 1854-5-6: with maps, plans, and wood engravings,

George Dodd (1808–1881) – Public domain

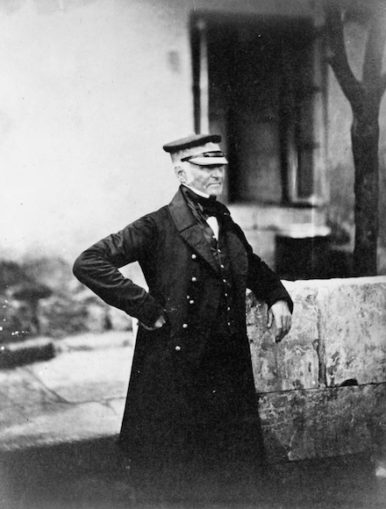

He was replaced by his chief of staff General Simpson, “a reliably commonplace man who usually wore a cap with a peak and who might be safely depended upon to behave without the slightest indication of originality.”

General Sir James Simpson, G.C.B.,

Fenton, Roger – Public domain

Now all the principals who had gone so happily, so irresponsibly, to war were dead – first St. Arnaud, then the Czar Nicholas, now Raglan.

Shame and heartbreak had killed them all in the end. But the war they had started dragged on to its bitter, inevitable conclusion.

In May the Queen had a medal struck in honour of her “noble fellows”.

The “noble fellows” were not impressed. “Half-a-crown and a pennyworth of dirty ribbon,” Sergeant Gowing, of Chorlton-on-Medlock, called it. The clasps, according to Paget, were known as “port, sherry, and claret”.

On September 8 they tried again. A full-scale all-out offensive was launched against the twin fortresses that covered Sebastopol, the Malakoff and the Redan.

And once again the British attack on the Redan failed utterly. The unhappy boys – for most of them were no more than that – of the Light Division were left to cross two hundred yards of open ground unsupported by artillery.

Trapped in murderous crossfire from the Russian batteries, whole regiments got mixed up in hopeless confusion.

“Then came the fearful run for life or death, with men rolling over like rabbits, then tumbling into the English trench, where they lay four wrote deep on each other,” wrote Russell in his dispatch to “The Times”.

But the French, attacking at the hour of the relief of the Russian trench garrison, fought their way into the Malakoff and held it against repeated counter-attack.

Combat dans la gorge de Malakoff,

Yvon Adolphe – Public domain

Their General MacMahon calmly signalled to his Allies: “All goes well. You may tell General Simpson that I’m here, and I shall stay here.” Thereby coining a phrase that has become part of history.

Patrice de Mac-Mahon, maréchal de France,

Horace Vernet – Public domain

Now the fate of Sebastopol was sealed. The Russians knew it, and suddenly withdrew from their defences to the north side of the harbour, burning and destroying as they retreated, leaving the Allies in possession of a blazing shell.

Again, for the same inexplicable reason, there was no thought of pursuit. And when Simpson tried to wriggle out with the excuse that he must wait to know the Russian plans the Queen acidly referred him to St Petersburg.

For all practical purposes, the Crimean War was over. Codrington, who had so ineptly led the ill-fated Light Division in its attack on the Redan, took over from Simpson. But there was little more fighting to be done.

The capture of Kinburn finally convinced Russia of the hopelessness of continuing the struggle; the French had grown weary of the war; and though Britain, smarting under the memory of her inglorious share in that final assault on Sebastopol, would willingly have gone on fighting, she could not do so alone.

So the war gradually faded into peace. The Treaty of Paris, signed in February, 1856, brought forth only one tangible result: the exclusion of Russian warships from the Black Sea – and even that only lasted 15 years.

The Congress of Paris,

Edouard Louis Dubufe – Public domain

And on April 29 – in a sickening atmosphere of futility – peace was proclaimed.

All over the Crimea that day British and Russian soldiers were fraternising and getting drunk. British cavalry officers were getting up steeplechases and breaking their necks.

Interpreters were busy arranging for the collection of Crimea crocus and hyacinth to be sent home to English gardens.

And in Whitehall Lord Panmure was writing to Sir William Codrington on the importance of bringing the men home beardless.

Florence Nightingale wrote in her journal that night –

“As I stood on the Heights of Balaclava and saw our ships in the harbour so gaily dressed with flags while we fired a salute in honour of peace, I said to myself, ‘More Aireys and more Filders; more Cardigans and more Halls. We are in for them all now and no hope of reform. In six months all these sufferings will be forgotten.”

And, of course, in a sense she was right. We have forgotten the sufferings that men experienced in those two years on the Crimea.

But some things more substantial have endured. There is, for example, her own splendid example of selflessness and humanity.

There is the lasting friendship, forged on the bloody ridges of Inkerman, between France and Britain.

And, above all, there is the memory of a British Army forsaken, shamefully betrayed – not for the first time or the last – finding its own salvation.

An army honoured in disaster by a new award for bravery – The Victoria Cross.

Alfred Knight‘s Victoria Cross at the British Postal Museum,

SwissArmchairHistorian – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Text:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

© Jerry F 2022