Fifth in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in December 1967 – Jerry F

Every Western cow town has its museum. Among the usual dusty clutter of old sewing machines, stuffed eagles and Indian arrowheads you can usually find — if you poke hard enough — evidence of the town’s wild and woolly beginnings.

The Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne, has three particularly grisly souvenirs.

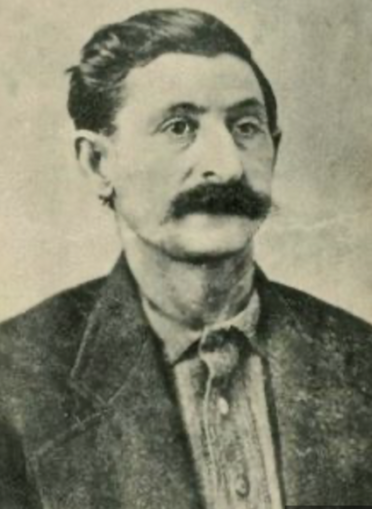

One is a collection of ropes’ ends, each patiently and intricately plaited. The other two belong together. The death mask of a handsome man with a nose like a hawk, who might have been a Roman emperor — if any Roman emperor ever wore a drooping cavalry moustache.

Beside it is a scrap of something that looks like un-tanned leather.

The whole turbulent story of the lawless West could be written round those three macabre exhibits.

The ropes’ ends were plaited in jail by Tom Horn. The most complicated of all was finished the night before they took him out and hanged him. The death mask is that of George Parrot, alias Curry, better known as Big Nose George. That piece of leather is actually a sliver of George’s skin.

Photograph of Tom Horn,

Phillips Collection – Public domain

Of the two stories, that of Tom Horn is the more interesting; as it is infinitely the more tragic.

For most of his life Tom Horn might have stood as a prototype for all that was best in the Old West.

The record shows that he was a brave and loyal scout, a peace officer who never abused his authority, a soldier who never knew fear.

Born of hard-working Missouri farm folk in 1861, Tom, a typical wanderer, ran away from home in his teens.

He did everything that makes a Western hero. He rode shotgun on the overland stage, drove a team, herded mules, worked as a top ranch hand.

In his photographs, even at the end, he looked exactly the sort of tall, slim, clean-cut Westerner idealised by Hollywood.

He was no drugstore cowboy either. He was a rodeo star in his twenties and later won the world championship for steer roping and tying.

As an Indian scout he had few equals. More than any other man he was responsible for capturing the Apache hell-raiser Geronimo. Horn trailed that cold-blooded savage for hundreds of miles to persuade him to come in and talk peace with the Army.

Tom Horn reached his peak as a Pinkerton range detective. His speciality was trailing and arresting train robbers. But he soon tired of it.

After the spectacular capture of Peg Leg McCoy, as vicious an outlaw as ever held up a train, Horn walked into the Pinkerton office in Denver and resigned.

Nothing more was heard of him for a year or two. Then one day he arrived quietly in Cheyenne. But this was a different Tom Horn. He was a hired killer now: paid so much a head by the cattle barons for shooting rustlers.

He went about his butchery as patiently, as conscientiously as ever.

“He would wait patiently for hours in a driving rain or drizzle, chewing on raw bacon, for the one perfect shot,” recalled James Horan and Saul Sann in their Pictorial History of the Wild West.

“He never left any evidence behind except a small rock under each victim’s head-his trademark.”

It was murder, executed neatly and precisely; the solitary crack of a rifle shot, then silence and death …

Something seemed to have happened to Tom during those lonely murder hunts. Perhaps the faithful watchdog had tasted blood too often.

For now not all his victims were rustlers. There was the occasional small rancher who had dared to stand up to the cattle barons. Horn hunted them down with the same brutal efficiency.

The limit was reached when the body of a 14-year-old boy, Willie Nickells, was found, obviously shot in an ambush. It was known that Horn had been gunning for his father, a sheep farmer.

Even so, the murder might have gone officially unsolved had not Joe Lefors, a deputy U.S. Marshal; taken a hand.

He made friends with Horn, who was drinking heavily by then. One night he heard the ex-lawman drunkenly boast of killing young Willie Nickells. Hidden witnesses heard him, too.

He was arrested and brought to trial. He denied making the confession to the end. But the jury found him guilty and he was sentenced to be hanged.

The decision rocked Wyoming, for Tom Horn had powerful friends among the cattle barons. They swore he would never hang.

They did their best to save him. They tried to blast him out of jail by dynamite, but the plot miscarried. Then Horn made a desperate breakout on his own. He was recaptured before he could get out of town.

On the day of his execution, soldiers patrolled the streets of Cheyenne. Tom Horn sat up all night finishing a rope’s end he had promised for a friend. Then, the rope finished, he laid it down and quietly, without fuss, Tom Horn walked out to his death.

There was tragic comedy in the rise and fall of Big Nose George Curry.

Big Nose George,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

George was probably the most successful rustler in the West. More than that, he ran a school of rustling.

Among his prize graduates were such brilliant exponents as Harry Logar and his brothers Johnny and Henry: later to become the stars of the most notorious gang “The Wild Bunch.”

Out of season George indulged in a little train robbing on the side.

There is no mystery about George’s life. But there is some mystery in his death. According to one version he was caught red-handed changing a brand and shot dead in a running fight with a sheriff’s posse near Castle Gate, Utah.

Another version has him being hanged by a lynch mob after an unsuccessful attempt to hold up a Union Pacific train in which a deputy sheriff was killed.

Whichever way he died his elegant, patrician features were modelled in wax, and strips of skin cut from his chest sold to souvenir hunters, who had them made into moccasins and pocketbooks. It seems a sad finale for a Western Bad Man: to end up as a pocket hook.

NEXT: Deadwood, and the ghost of Wild Bill Hickok.

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2022