International Festival of Glass, Stourbridge, August 2022

Earlier this year, around May-June if I remember correctly since it was right in the midst of the chaos of our moving home, it was with some excitement that Mr S and I read an email which had popped into our inbox, informing us that the eighth International Festival of Glass was to be held in just a few months’ time. Given the recent unforgettable period of Covidiocy, it had been a few years since the Festival had managed to run and, with one or two other distractions happening in our own lives, longer still since we’d been able to attend.

We both love glass and are small-scale collectors in our own way. It is an incredibly versatile material, and there are many different techniques available for creating art in glass. We’d thoroughly enjoyed the last Festival we’d attended so, without further ado, we started making our plans to go. What’s more, this time the trip was going to be a little easier for us to manage, as the Festival takes place in Stourbridge. For those of you unfamiliar with it, this is a market town in the West Midlands, in fact in the Black Country, just a short distance down the road from where we live now… well, almost.

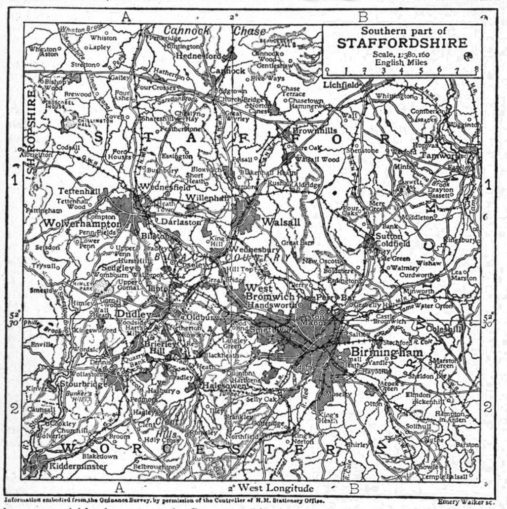

Now the Black Country is a fascinating area, with a rich and varied history worthy of an article in its own right. Perhaps a Puffin more knowledgeable than I could oblige? Defining its boundaries is not quite straightforward though and remains the subject of much debate. The closest I will venture is to say that some, if not most of the region, falls into South Staffordshire, to the northwest of Birmingham and south of Wolverhampton.

Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Vol. 25, Page 758, public domain

The town of Stourbridge lies on the western edge of the Black Country, and what is known nowadays as the Stourbridge Glass Quarter was once the world capital of glassmaking. It has stood proudly as a major production centre for glass for around 400 years. A little more of the history is to come. Right now, our first priority was to get ourselves there.

New territory for us, as the last time we’d headed to Stourbridge we still had a car. About 57 miles away from home as the crow flies, by train it’s about an hour and a half away, but the journey involves three changes. This time, we’d be travelling via Wolverhampton (somewhere we knew not a jot), then onwards to Smethwick Galton Bridge (er, where?), and Stourbridge Junction before changing for the last time to get to Stourbridge Town.

The final stage was to prove quite exciting for us as we’d be travelling on Europe’s smallest branch line, the sweet Stourbridge Shuttle. It’s just a 3-minute journey in what looks like a push-me-pull-you, double-headed, overgrown minibus!

© SharpieType301 2022

Despite our moderate concerns since it was taking place on the Friday before the August Bank Holiday weekend, the train journey went smoothly. We arrived at Stourbridge ravenous though, as we’d been too excited for breakfast. No problem, as we found that there’s a delightful little social enterprise café based in Stourbridge High Street, just outside the Stourbridge Interchange. Cafe 105, it’s called, and it sells delicious food. We found it a nice friendly, clean, inexpensive place for a bite to eat.

From Stourbridge town, we had to get to where we were staying. We hadn’t managed to book anywhere in the town itself, but close by in Brierley Hill. It wasn’t far from the old Hanson’s Round Oak pub, named for the Round Oak Iron Works (later Steelworks) that the town was famed for. No problem getting there either, the number 6 bus took us right where we wanted to go! As a little aside, where we were staying was off Bank Street. In the early 1970s, the Brierley Hill Civic Hall, at one end of the street (right next to the cop shop), staged some of glam rock band Slade’s first gigs. As a venue, it’s still going strong.

Keys collected, luggage left locked in our room, it was back on the bus to Stourbridge. Our first port of call was the Ruskin Glass Centre. This or rather the Glasshouse College, was the Festival’s main site, although events were taking place at other venues across the area. This year’s theme was contemporary glass from East Asia (South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and China) and there was an exhibition, ‘Expanding Horizons’, we were itching to see. Based at the Glasshouse Arts and Heritage Centre, thirty-four East Asian glass artists, some renowned, others promising, had submitted works for display.

Oh my! The range of different glass techniques and the quality of the work was exceptional. Most of the pieces were for sale, and I’ll admit we were tempted, but the prices were pretty extraordinary too. Just to give you a little taste of the delights, this was the first piece I fell for. By young South Korean artist, Youngho Park, this beautiful object, reminiscent of fishing nets, was a snip at less than £15 grand but, regrettably, just too darn large to fit in our one bedroomed flat. It had to be nearly three feet in diameter!

© SharpieType301 2022

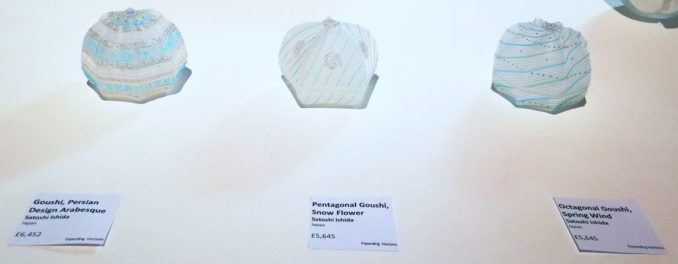

At a much more manageable scale, three delicately subtle small, lidded boxes, or ‘goushi’, reminded me of the sea urchin shells I used to collect on child-hood Gower beach walks. Exquisitely made using the ancient Pâte de Verre technique, by Japanese glassmaker Satoshi Ishida, son of the acclaimed Japanese glassmakers Wataru and Yuki, I’d have taken these home in a heartbeat… if it wasn’t for those price tags. These lovely pieces seemed to glow with an inner light—something quite impossible to capture with just a phone camera.

© SharpieType301 2022

Pâte de Verre is a fascinating technique with origins that can be traced back to the second millennium BC and is one of the oldest known forms of glass working. The Mesopotamians first used this process, carefully described in cuneiform texts, to produce decorative coloured inlays for jewellery and sculptures, and both ancient Egyptian and some early Roman glass was made in the same way.

Each piece produced is unique, as powdery crushed glass (frit), mixed with a binder, is placed between a male and a female clay mould, then fired. The mould is then carefully chipped away from the finished glass, which can be polished or further decorated. Much later, the original clay moulds used by the Mesopotamians were replaced with wax, the so-called ‘lost-wax’ casting method which is also used for bronze castings. One advantage of using an inner and outer mould is the potential for fantastic detail and the ability to determine the thickness of the finished piece. As Ishida has done with these pieces, additional coloured decoration can be added with coloured glass powders in their binder being applied (almost ‘painted’ on) with subsequent firings, to build up the finished piece.

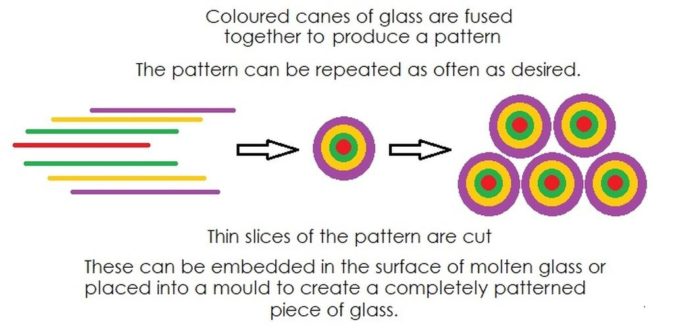

The range of techniques seen in this one exhibition was wonderful. Daisuke Takeuchi uses the murrini technique, where patterns are made in a glass cane that are only revealed when the cane is cut into thin cross-sections. Imagine the writing through a stick of seaside rock.

© SharpieType301 2022

A well-recognised murrini pattern is millefiori, made by Venetian glassmakers on the island of Murano, where a number of different canes, each made in a flower or star shape, is brought together and used together in large numbers, perhaps in a mould as seen in the bowl below, to give the final pattern.

© Pauly & C. – Compagnia Venezia Murano, licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Kyoto-born Daisuke Takeuchi takes this technique to another level with his extraordinarily beautiful designs, tiny objects with intricate detail and jewel-like colour. Again, my photograph simply cannot do their complexity justice. Being small, these would be easily overlooked as they were surrounded by much larger, more striking objects. But that would have been to miss a treat for the senses.

© SharpieType301 2022

Completely different again is the work of Hiroshi Yamano, one of Japan’s foremost glass artists. With its nod to the ancient Kanō school of painting, he draws his designs from nature, notably here the fish and the Mukuge flower (which we know as the Rose of Sharon). The quality of his work is incomparable and is reflected in the price of this stunning piece, at over £24,600. This a sizeable piece of work, and I can’t begin to understand the variety of techniques used in its production. I’m simply delighted to have had the chance to see it. We spent a long time viewing it from side to side, in awed wonder. The highly polished fish sculptures refract the light, making them shimmer, almost magically appearing to move as you step towards them, and the artistry of the bowl took my breath away.

© SharpieType301 2022

We knew that there was so much more to see at the Festival, and only a few short days in which to do so. We reluctantly dragged ourselves away, but as we walked out of the Glasshouse Arts and Heritage Centre, we stopped to admire the ‘Vessels of Memory’ exhibition. I had a particular interest in this exhibition, as the techniques used stem from the work of scientific glassblowers. Those are the dedicated folk who specialise in producing high-tech laboratory glass apparatus, by manipulating glass with a gas torch flame (a.k.a. lampwork). Being something I have tried to do myself (rather poorly, I’m sorry to say), I have a pretty good idea of the skill the exhibits reflect.

The ‘Vessels of Memory’ exhibition focused on the glass ships in bottles, made in the UK, and displayed the personal collection of 150 ships in bottles on loan from Dr Ayako Tani, who has been researching their manufacture. Given the lighting and reflections, my photographs couldn’t begin to show the extraordinary complexity of these ships, but you can see the collection for yourselves here: http://www.vesselsofmemory.com/collection.html

I would cheerfully give my eye-teeth for just one of these ships, but if forced to choose it would be one of the less complex pieces. A small Greek cargo ship under sail, in a bottle shaped like a two-handled, oval-bodied, ancient Greek pointed amphora.

© Ad Meskens, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

This small ship in its bottle was listed as coming from an unknown maker and I felt it was quite stunning. Perhaps it made its mark as I have a particular interest in this form of ceramic trade container, and the goods they transported, but that’s a tale for another day.

Onwards, and actually just upstairs, to the British Glass Biennale exhibition. This is a judged exhibition with votes cast by the public, open to “artists, designers, craftspeople and students working in all areas of contemporary glass practice or using glass as a key design element” and is always a sight to see. This year was to be even more special as it incorporated the inaugural International Bead Biennale. Beads? And from around the world? My ears pricked up immediately.

Wow! was my first impression. Set in a large, well-lit, barn-like hall, the items on display were outstanding. To my shame, I got so carried away at this exhibition, that I utterly forgot to include the labels to indicate the artist (and price, if the piece was for sale) for most of the pieces. Sorry, glassmakers! We’ll have to make do with simple awe at the glass that we saw.

I was immediately struck by a stunning, wall-mounted piece. A dragon. Probably a good three feet in height, and not far from that across, this was striking piece indeed. Lampwork again, and the subject matter of course to my taste, but the sheer scale and delicacy of this work made it fantastically compelling. I do wish I could remember whose work this is, as I’d love to see more of her art.

© SharpieType301 2022

As we walked past the trestle tables laden with extraordinary glass, oohing and aahing, it was hard to concentrate but a few pieces just cried out to be recorded. Some of these are, sadly, missing here as my photographs just didn’t show their beauty, but the series of ‘quill pens’ in their inkpots, all made of glass was perfect. I honestly thought that the feathers were just that, until we got closer. Nope. Each is subtle, elegant glass, sculpted with beautiful colour and delicate detail by Layne Rowe.

© SharpieType301 2022

Layne has a studio in Cambridgeshire and created a series of these ‘Quill n ink’ pieces as part of his ‘Ornithology’ project. They are each individually named and accompanied by a poem which reflects the feather. If I’m honest, I feel he’s a far better artist than poet:

The soldier

An Eagle feather

Using the enemy’s blood as ink

He writes of war

Myself

A poetic Blue phoenix

He writes with dreams

Dipped in imagination

And create a better world

A Beauty

A Swan feather

With Dazzling White ink

She writes of this repulsive world

A Mourner

A ravens feather

Black despairing ink

He writes of death

The next gem I fell for was a piece called ‘Cassito’ by Katherine Huskie. She specialises in blown glass pieces but, unusually, in this object she has decorated it by adding texture to the inside of the bowl, rather than the outside. This means that it would be beautifully smooth to hold, yet the light passing through casts shimmering, water-like patterns beneath the piece, adding to its beauty.

© SharpieType301 2022

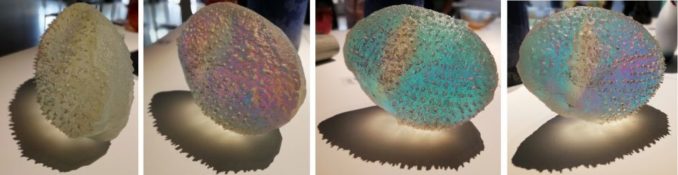

Strangely the next piece I was drawn to, by Jon Lewis, may seem a little lacklustre at first glance. From a distance, it looks like a large knobbly yellowish lump.

But this lump, called ‘Moon Rock’ holds a secret. It’s produced as a cast glass piece, hand cut to give that distinctive, knobbly, almost puffer fish texture. But the artist has used dichroic filters within the glass to cleverly reflect the light. As I moved clockwise around it, the piece appeared to glow in shifting iridescent colours from within. Far from an ugly yellow lump now, the colours bring it to life, giving it an unexpected ‘butterfly wing’ beauty. I wish I’d thought to take a video rather than a series of stills, but you get the idea. It seems my tastes mirror those of Barbara Beadman, Master of the Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers, as Jon, together with Layne Rowe of the quill pens above, were awarded joint runners-up in the Arts & Crafts Award for 2022.

© SharpieType301 2022

A short distance away from this and other large exhibits, was a table with a series of smaller objects. The following exhibit got my attention—is it time for tea? Well only if you don’t prize your gnashers, as each of these sweet fancies is made of glass. Quirky and cute, they looked good enough to eat!

© SharpieType301 2022

So many wonderful things, displaying every technique in the glassmakers arsenal. The lampwork I’ve already mentioned is common. But there’s also ‘hot glass’ work, including blown glass, solid sculpted glass, and cast glass. ‘Warm glass’ techniques, encompassing ‘slumped’ or ‘fused glass’, ‘pressed’ or ‘kiln cast glass’, ‘bent glass’, and ‘pâte de verre’, not forgetting the ‘cold glass’ techniques. Once the glass has cooled, it can be ground, polished, etched, sandblasted, cut, engraved, or stained to further enhance it.

It appears that I share the opinions of the Glass Society too, as I was delighted by a sturdy pâte de verre exhibit by Rachel Elliott which she calls ‘Maelstrom’. This comprises a small grouping of nautilus structures, their hollow chambers surrounded by a sponge-like mass of sintered frit. She was awarded the Society’s ‘Uniting the Planet’ prize for this piece.

© SharpieType301 2022

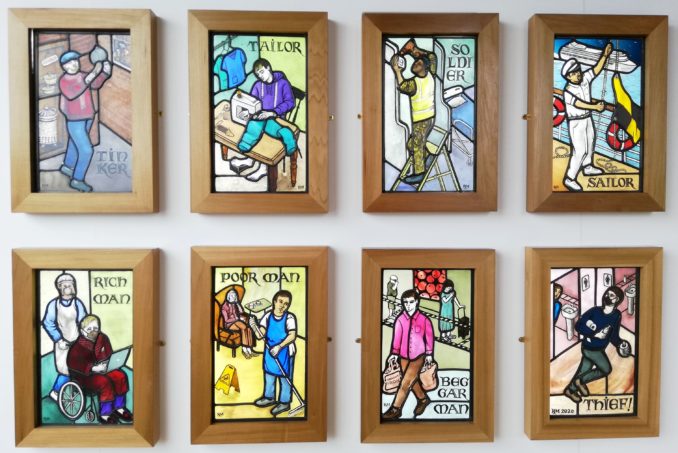

One of the other exhibits I loved was a series of eight stained glass panels inspired by the old nursery rhyme and fortune telling song ‘Tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief!’. Young girls would use this rhyme when I was a lass (yes, OK, I am aware that this was quite a few years ago!), counting cherry stones or the like to foretell who they might marry. Artist Rachel Mulligan from Surrey has reimagined the rhyme with a contemporary twist to create this series, which I absolutely loved. Given that it was completed in 2020, the ‘thief’ panel really made me giggle!

© SharpieType301 2022

The range of different art, all using the same medium but with greatly differing techniques, was a joy to see. Contrast the panels above with this set of small roundels. Entitled ‘Yellow Lichen’, this set of subtle, pocket-sized sculptures by Nina Casson McGarva pulls you in for a closer look, to discover tiny details quite overlooked until you move nearer. I almost passed them by, but something made me look twice. In fact, this piece ended up winning the Arts & Crafts Award for 2022.

© SharpieType301 2022

And then there were those beads… A relatively modest collection set aside behind a panel, it would have been easy to miss, but I’m glad we didn’t. Small these may be (who wants an earring you can’t lift?), but they were beautiful, and covered the whole gamut of glassmaking techniques. Here’s just a tiny taste of what was displayed, with those at the top left my particular favourites.

© SharpieType301 2022

After this marathon, on what was an extremely hot day, it was time to sit down for a while with a well-deserved drink. The Ruskin Glass Centre is well supplied with places to find sustenance, and two bottles of cold water were quickly sourced, though the locally brewed craft beers did look rather tempting.

It was such a glorious day we had to sit in the sun, and the pool with the splashing sounds from its sculptural waterfall (glass, of course) was the perfect spot to relax and watch the world go by. The resident koi patiently patrolled the perimeter, each one hoping that somebody might drop a few crumbs into the water.

© SharpieType301 2022

Rested and refreshed, we had a little mooch around the studios at the Ruskin Glass Centre. The Natroma aromatherapy skincare range smelled delicious, and the soaps were tempting, but there was so much to see. We thoroughly enjoyed speaking to some of the artists working at the Ruskin.

Stonemason and sculptor Philip Potter is a fascinating chap with an interesting background. He showed us around his Kairos Sculpture workshop, explaining the projects he has in progress and telling us a little about the stone he uses. I could have listened to him for hours.

Master-craftsman and woodworker Jamie Hubbard, the ‘Worcestershire Cabinet Maker’, has an impressive track record. His work ranges from cabinet making, and boat building, to the restoration of period furniture. He also designs and makes bespoke furniture and artwork, and together with his neighbour, glassmaker Jo Newman, created a stunning new font from an old pulpit at Holy Trinity Church in Wordsley. This project fitted well with his philosophy of reusing using old timber that would otherwise be dumped in skips, burnt, or simply left to rot.

He also has a fine sense of humour and, aside from his wonderful wooden pieces, his workshop sports a fully articulated alligator (OK, it’s actually Tick-Tock the Crocodile, but I like alligators) which he designed, made, and ‘inhabited’, for the Peter Pan panto at Christmas.

© SharpieType301 2022

We spent some time exploring the Centenary Exhibition of the British Society of Master Glass Painters. There were some gorgeous panels using both traditional and modern techniques, demonstrating the extraordinary range of contemporary stained glass. I can’t say all were to my tastes, but I loved the more traditional panels, especially Tamsin Abbott’s ‘Longing’ and Veronica Smith’s ‘The Sentinel’. My favourite was Deborah Lowe’s ‘Wish I was here’, a scene depicting the view from the top of Whitby Abbey steps looking out over the harbour. You can enjoy the exhibition online, and find out more about each panel, here: https://www.bsmgp.org.uk/news-events/events/exhibitions/

To be honest, as wonderful as it was, by now we were about glassed out for the day, and weary from the travelling too. It was time to head for the peace and cool of where we were staying, stopping off at the local Asda to get a picnic dinner. We briefly thought about wandering along to the local pub for a drink, but our poor feet decided that was a step too far!

The next morning was Saturday and, suitably rested, we wanted a ‘proper’ breakfast before we walked along the canal to the Red House Cone and the Stourbridge Glass Museum. I’d done my research and there was a café on Pensnett Road near to the canal, Sarah’s Diner. Basically, a caravan at the edge of an industrial estate it couldn’t be beaten, though the portion size nearly beat us! A keto-friendly plate of hand-tied sausage, home-cured bacon, mushrooms, and free-range eggs, the quality shone through, and it was lovely.

So off we set, full and happy, along the Stourbridge Canal, from just below the Grove Pool past Leys Junction and the start of the series of locks leading down to the Red House Cone. What a wonderful walk it was too. So peaceful, and so much to see.

© SharpieType301 2022

We decided we’d head for the Stourbridge Glass Museum first, so walked past the Red House Cone, admiring the sturdy brickwork cone across the water. There was a hot glass demonstration in progress when we went into the Museum, with Darren Weed and Allister Malcolm showing how their gorgeous, dimpled bowls with sterling silver leaf design are made. This took place in Allister Malcolm’s Glass Studio, and there were pieces on display to buy. Ah, this was a challenge, but more than we could afford!

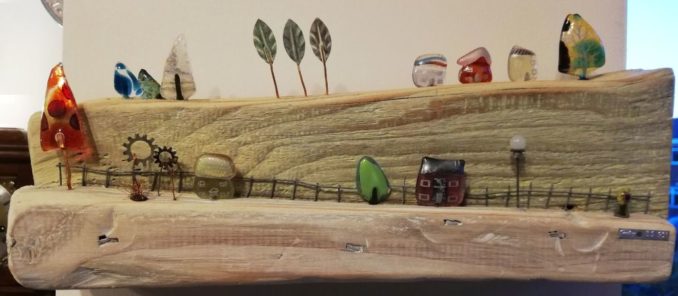

What really caught our eye were the Driftwood Landscapes made by Terri Malcolm. She creates mixed-media pieces from reclaimed and recycled material, including driftwood, bits of old metal, and offcuts from the glass studio. As a result, every piece is a one-off original. Whimsical, wonderful, and in our price range. Without a doubt one was coming home, but it had to wait to be picked up until the end of the Festival. Here it is, happily relocated to our living room wall!

© SharpieType301 2022

One of the highlights of the trip was speaking to one of the true masters of glass decoration, Terri Colledge. Terri’s work is greatly sought after worldwide. She creates breath-takingly beautiful cameo glass pieces. The cameo glass technique is where a design is produced by etching and carving through fused layers of differently coloured glass. A ‘blank’ piece typically comprises a dark-coloured under-layer superimposed with a lighter-coloured, often opaque white, over-layer. This outer shell is etched or carved away, leaving the lighter design standing out in relief. Cameo glass is a bit of a passion of ours—a few years ago we commissioned a piece by another cameo glass master, Helen Millard, to celebrate our anniversary.

A gently self-effacing lady, Terri engraved the 21st century replica of the famous Portland Vase, the best-known piece of Roman cameo glass in the world. Her ‘Stourbridge Twenty Twelve Portland Vase’ is on display at the Museum. Using a sandblaster and a high-pressure, flexi-drive dental drill, there’s a video of Terri carving a circular base disc (though this was not part of the original vase) of the replica here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ie0Yr_QL-7c

To give an idea of the colours of glass that might be used, in cameo and in other glassmaking, there is a display on the wall of the Museum which I found fascinating. I included a section on the use of different minerals to produce the desired colours in glass in one of my earlier articles ‘A Glass Half Full’, and there’s another interesting piece about how coloured glass is produced here: https://www.compoundchem.com/2015/03/03/coloured-glass/

© SharpieType301 2022

There was so much more to this trip than we’ve seen so far, but for that you’ll have to wait for Part Two.

© SharpieType301 2022