The Needle Gun

Every once in a while in all fields of engineering there comes along an innovation that so revolutionises the existing technology that it makes long accepted ways of doing things obsolete and then in turn stimulates other new approaches and ideas. In the field of firearms technology some of these changes have been long-lived as, for example, the invention of the flintlock ignition system that made carrying a length of burning rope to the battlefield unnecessary and endured for 200 years. Many other developments were much shorter lived as was the case with the fulminate percussion cap that having made flintlocks obsolete remained in military use for no more than 40 years before itself being replaced by the self-contained, centre fire brass cartridge.

Along the way numerous other ideas were soon proved to be completely impractical and unsuited for widespread adoption while others, after enjoying a brief period of glory were quickly consigned to the dustbin of history. It is these unusual and generally long-forgotten weapons and their ammunition that are currently my principal area of shooting interest.

This article considers two military rifles, one Prussian and one French that for thirty and for five years respectively represented the pinnacle of firearms technology. These two rifles which themselves are now long obsolete and for the most part forgotten are usually referred to as the ‘Needle Guns’.

The von Dreyse Zündnadelgewehr (Needle-ignition rifle) ( 1841-1871)

In 1824, Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse (1787-1867) a Prussian gunsmith who had been apprenticed to the Swiss gunsmith and manufacturer Jean-Samuel Pauly (1766-1821) at his Paris factory from 1809 to 1814 began experimenting with the design of a bolt-action, breech loading rifle. The result of von Dreyse’s genius which was adopted by the Prussian military in 1841 utilised a paper cartridge containing a 15.4mm (.61”) ‘Langblei’ or long-lead bullet, a 74 grain black powder charge and, for the first time in a military rifle, its own means of ignition in the form of a fulminate cap placed inside the cartridge. This removed the need to place a percussion cap on a nipple to be exploded by a falling external hammer as was common practice at that time.

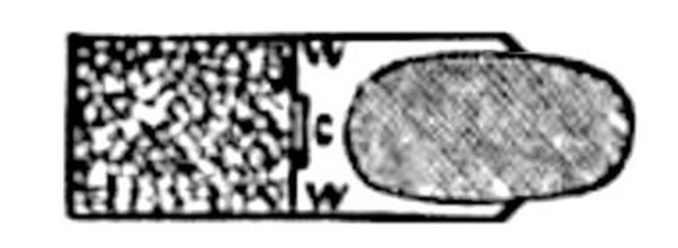

To modern eyes the Dreyse cartridge is quite bizarre in that the bullet was shaped like an acorn and was contained in a papier mâché cup known as a sabot. When the trigger was pulled, a long steel needle pierced the thin card base of the cartridge passing through the whole of the powder charge before striking the fulminate material at the base of the sabot and igniting the gunpowder. The resulting explosion discharged both the bullet and its sabot which separated from the bullet on exiting the muzzle having cleaned the bore of fouling during its transit and prevented the bullet from contacting and depositing lead residues in the rifling.

Here we should pause to consider briefly the use of fulminates in firearms ignition systems. Scottish clergyman the Reverend Alexander Forsyth, frustrated by the slow ‘lock time’ of his flintlock sporting guns that made shooting flying birds extremely difficult, had in 1807 patented a complicated but effective ‘scent bottle’ lock that overcame this problem by delivering a measured amount of fulminate powder onto a nipple that instantaneously ignited the gunpowder in the chamber when struck by a falling hammer.

In 1812, Jean-Samuel Pauly who was then working in Paris, had taken what to us blessed with the benefit of hindsight now seems the logical step of incorporating fulminate powder into the centre of the metal base of a cardboard bodied cartridge containing powder, wads and shot to create what to all intents and purposes was the modern shotgun cartridge. Incredibly, this was in the year that Napoleon marched on Moscow and only three years before the Battle of Waterloo. The Emperor, however, rejected this advanced technology on the grounds that: i) it was too complicated and ii) that it required two different powders in order to function. Had he listened to Pauly who was a good 60 years ahead of the field at this time, the outcome at Waterloo and subsequent world history might well have turned out very differently. Nevertheless, it seems strange that von Dreyse who was working for Pauly at the time and who must have been fully conversant with his work did not make use of this major step forward in his own cartridge design. As the technology to ‘draw’ brass into cartridge cases would not be available until the 1860-70s there was little alternative but to use paper for cartridge manufacture.

To disguise the fact that the Prussians now had the first bolt-action rifle ever to be adopted into military service, it was designated ‘Das Leichtes Perkussiongewehr M/41’ or The Light Percussion Rifle Model of 1841 and by 1859 the entire Prussian infantry had been equipped with this new weapon.

The needle rifle first saw action in street fighting in the May uprising in Dresden in 1849. In the Prusso-Danish or Second Schleswig War of 1864 it routed the Danish army and in 1866 during the Austro-Prussian War the rifle’s high rate of fire (at least five times that of a muzzle-loader) and its ability to be loaded and fired from a crouched or prone position or even while on the move proved decisive against the Austrian Lorenz muzzle-loaders that could only be loaded while stationary and in an exposed, standing position. At the battle of Nachod (June 27 1866) Austria lost 5487 men to the Dreyse needle rifle, five times the Prussian losses. This was repeated a week later at Königgrätz when 45,000 Austrians were killed, wounded or captured against 9,000 Prussian casualties. These unsustainable losses led to the Austrians suing for peace in August of that year.

Criticisms of the Dreyse rifle

Not surprisingly, news of the Prussian wonder weapon spread rapidly and soon captured examples and specially manufactured copies were being examined and evaluated by various governments. The British trials of 1849-51 concluded that:

- The mainspring was too delicate and prone to break

- The needle quickly fouled and operating the bolt became progressively more difficult as deposits accumulated

- The barrel was prone to wear at its junction with the chamber

- The escape of gas from the breech became progressively more noticeable as fouling built up, and

- The effective range was only around 600 yards as opposed to the new Minié rifle’s 1200 yard range.

Other criticisms were that needles regularly failed due to their being exposed to the flames and heat of the combustion chamber though to be fair, soldiers were each provided with two spare needles and could replace a broken needle in the field in around 30 seconds.

The main problem with breech loading weapons of the period however was obturation or sealing of the breech to prevent the discharge of hot gases and unburnt particles of gunpowder backwards into the face and eyes of the shooter. In the M/41, this was achieved by mating a convex tapered rim on the chamber with a concave taper on the bolt face that provided a reasonably good conical, metal-to-metal seal when the bolt was locked into position. Modern shooters of these rifles claim that leakage from the breech of the Dreyse is minimal but, it has to be remembered that they are using them in ideal conditions where they can clean and maintain the conical faces at their leisure. Firing ten or more rounds per minute while under return fire in the heat of battle would of course have been a totally different matter.

The French Response – Le Fusil d’Infanterie Modèle 1866 ‘Chassepot’ (1866-1874)

As relations with Prussia had been tense for many years, the French were understandably extremely concerned about their potential enemy’s technological advantage and quickly applied themselves to producing an effective bolt action rifle of their own. Although by this time self-contained metallic cartridges were beginning to appear particularly in America, they were only suitable for relatively low powered and short range pistol calibres as was the case with both the Spencer and Henry rifles. As the French did not at the time have the technology to produce the copper alloys needed to manufacture high quality brass cartridge cases capable of withstanding full military loads, they too opted for a paper cartridge. The result was the adoption of Antoine-Alphonse Chassepot’s (1833-1905) much improved version of the Dreyse which despite its technological innovation was nevertheless to all intents and purposes obsolete before it even went into production.

Instead of a heavy, large calibre bullet like that of the Dreyse, the Chassepot fired a lighter 11mm (.45”) projectile over a larger, 86 grain powder charge making the rifle ballistically far superior to its competitor. A smaller, faster moving projectile has the advantage of shooting flatter and thus being dangerous over a greater area of the battlefield than a slower bullet with a rainbow trajectory. Other advantages are that soldiers can carry more rounds of lighter ammunition and more projectiles can be made from a given amount of lead.

The most amazing feature of the Chassepot, however, lay in the way that it sealed the chamber from the leakage of combustion gases. Instead of a precision-machined metal-to-metal joint that rapidly became fouled, the Modèle 66 rifle had a moving bolt head that held a circular, vulcanised rubber obturator which on firing was distorted sufficient to completely seal the chamber.

Unlike in the Dreyse, the firing needle did not have to pass through the powder charge as the fulminate material was contained in a copper cup glued into the base of the cartridge. This made the needles longer-lived than those of the Prussian rifle but they too did occasionally break and their replacement necessitated stripping the bolt, a simple enough task with the kit of tools that every infantryman carried. New rubber obturators could easily be fitted in the field. The main problem, as with the Dreyse, was the rapid build-up of fouling in the breech from the combustion of the black powder which together with unburnt paper residues eventually made loading the rifle extremely difficult and thorough cleaning of the chamber essential.

The Needle Guns go to War

In 1870, after a proposal to put a Prussian prince on the Spanish throne and confident of their Chassepot rifle’s superiority over the Prussian Dreyse the French were eager to reassert their pre-eminence as a European power. By declaring war against the North German Confederation led by Prussia, Bavaria, Baden and Würtemburg the French played straight into the hands of Otto von Bismarck who at the time was actively seeking just such a cause under which to unify Germany. France formally declared war on Prussia on 16 July 1870 and invaded German territory on 02 August.

From the outset, the French Chassepot rifle with its long range capability proved itself more than a match for the German Dreyse inflicting heavy casualties on distant troop formations and in particular the officers who were leading by example, all while safely beyond the range of return fire.

The deadly effectiveness of the fusil Modèle 1866 is illustrated by this account following one of the early engagements of the war:

“The story of the battle was told by the dead. From Sulz, where the Crown Prince had established his head-quarters, a road runs westward to Würth which is situated in the bottom of a valley between two ranges of cultivated and wooded hills, the higher or western ridges being occupied by the French. The centre of the German position was where this road winds down the heights into the town, and here on the morning after the battle the spiked helmets and needle-guns were brought in cartfuls from the eastern slopes. There could be no doubt that the Chassepot had told fearfully upon the German ranks from a distance.”

It is hardly surprising that after examining a captured Chassepot, a German officer described it as, “a beautifully worked murder weapon; a dainty little thing.”

Had the war been fought purely with small arms at long distance then no doubt the French would have quickly prevailed but unfortunately for them, the Germans were far better trained, better organised and more flexibly deployed. They used their extensive railway network to move troops and equipment quickly and efficiently to where they were needed and began to employ encircling tactics rather than mounting suicidal frontal attacks. The Germans also had one major advantage over the French and that was their Krupp 6-Pfünder Feldkanone C/61, a steel barrelled, breech-loading artillery piece that fired shells tipped with reliable percussion fuses that exploded on impact.

At this time the French were still using the bronze barrelled, muzzle-loading La Hitte cannon with its unreliable and inefficient time-fused shells that were far slower to load and fire than the Krupp six pounder and furthermore had a much shorter range. They also had 210 primitive, 25 barrelled machine guns or mitrailleuse (rather like Gatling guns) that were deployed in groups of six that could fire volleys of shots but, being mounted on artillery carriages these were difficult to traverse and, except on rare occasions, were of little practical use on the battlefield.

At the Battle of Sedan in September 1870 when Emperor Napoleon III and 104,000 of his soldiers were taken prisoner Bismarck sought a legitimate body with which to negotiate an armistice but when the news of the Sedan defeat reached Paris, the Second Empire was overthrown and a body calling itself the Government of National Defence declared its intention to continue the war. Seeing no alternative, Bismarck besieged Paris which, after a great deal of hardship, capitulated in January 1871.

Subsequent analysis of the casualties on both sides showed that 53,900 French soldiers, (70% of the casualties) fell victim to the Dreyse rifle against 25,475 (96%) Germans shot with the Chassepot. While the Chassepot inflicted far more damage to flesh and bone than had ever previously been seen on the battlefield, superior German organisation, tactics and their use of more advanced artillery had clearly swung the balance in their favour.

The Rapid Demise of the Needle Gun

Although the Dreyse rifle, which at the time of its introduction was the most advanced military rifle in the world, ceded this distinction to the far superior Chassepot 25 years later, both weapons were made obsolete by the development of the .577-450 short-chamber Boxer cartridge that was adopted by the British Army in 1870 for its new Martini-Henry rifle.

In response, in 1872 Prussia re-equipped with the Infanterie-Gewehr Mod. 1871 Mauser which used the 11.15x60R (.43 Mauser) cartridge while the French modified their existing Chassepots to take a conventional 11mm brass cartridge. This rifle known as the ‘Gras’ after its designer Colonel Basile Gras (1836-1901), was officially adopted in 1874.

The Needle Gun had served its purpose remarkably well but it was now surplus to requirements. The paper cartridge had had its day; the self-contained, drawn brass cartridge was clearly the way forward.

© text & images except where indicated Tom Pudding 2022