George Eastman Museum No known copyright restrictions

Uncle Fred’s Early Life

‘Uncle Fred’, as we all called him, was, in reality, my maternal grandfather’s uncle, and my great great uncle. He was the only other member of my grandfather’s family I ever knew, and I cherish the memories of my frequent childhood visits to see him at his house in West Ardsley.

He was born in December 1876 in Dewsbury, the eighth child (of nine) of John Baruch and Barbara. Surprisingly, he was christened ‘Fred’, not Frederick: perhaps his parents got bored with choosing new baby names every few years! Thanks to the 1880 Education Act, Fred would have had five years’ schooling, between the ages of five and ten. His father died in 1889, and in 1891, at the age of fourteen, Fred was a wool weaver, a role which he would have worked up to, having been employed in the mill since he was ten.

How, eight years later, he had moved from Yorkshire to become a London Metropolitan constable bears some examination. His motivation may have been simply to improve his lot in life, but his home circumstances had also changed dramatically. In 1892, his brother, Henry, had married Sophia, and they had three sons in the ensuing six years, the last of which was my maternal grandfather, Ernest. Unfortunately, Henry turned out to be a drunkard and wife-beater, and, soon after the birth of my grandfather in 1898, Sophia left him and the three young boys (and would not be seen again for 50 years). The eldest boy, Percy Clarence, was brought up by Sophia’s family, whilst my grandfather and the middle son, John Willie, were brought up by Uncle Fred’s mother, Barbara. Two toddlers in the house may have been the final straw for Uncle Fred.

Whatever the motivation, Fred clearly qualified when he applied in January 1899. At the time, candidates had to be 22 – 27, at least 5’ 9” tall and “read well, write legibly and have a fair knowledge of spelling”. In addition, a constable had to be “generally intelligent and free of bodily complaint”.

Fred was 22 years and 1 month old, 5’9” tall and weighed 12st 8lbs, with a 36 1/2” chest.

By this stage, Fred had become a drayman, giving a Mr. J. Potts of Dewsbury as his referee. While I have been unable to link Fred to any particular brewery, the Dewsbury and Batley Brewery, established in 1896, was by far the largest in the town, so it may well have been his employer.

Metropolitan Police

Uncle Fred came into my mind on the back of the various current problems in the Metropolitan Police because he was a London PC at quite a different time in its history, when the Met also had problems with its men, although for very different reasons.

To put this period of our history in context, Queen Victoria was still on the throne; Ireland was still part of Great Britain, although the Fenians were committing atrocities in Ireland and on the mainland in the name of Irish independence; the Second Boer War was underway; the Suffragettes were active and the Labour Party would be officially formed in the following year.

Formed in 1829, by Robert Peel, with around 3000 men, by 1899, when Uncle Fred joined, the Metropolitan Police Force had expanded to 16,000. Over the same period, the population of London had grown from 1.5 million to over 7 million.

One of the main problems in the maintenance of the Force was the rapid turnover of staff, with as many as half leaving during their first year, either voluntarily or through dismissal, usually for drunkenness. It was for this reason that the incentives to stay were gradually extended to include a housing and coal allowance (or accommodation in a communal house), free medical care, recreational facilities, sick pay and a pension.

The work was arduous, 13 days out of 14 on duty, with only 10 days’ paid holiday a year. Pay was 25s 6d a week, rising by 1s a week to a maximum of 33s 6d. In today’s values, this equates a salary scale of £16, 200 – £20,000 p.a. Police constables contributed 2.5% towards their pensions and benefits.

The area covered by the Metropolitan Police was 700 square miles, including all boroughs within a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 15 miles from Charing Cross, excluding the City of London and the Inns of Court. This area was allocated to 22 divisions delineated by letters of the alphabet. In addition, the Met was responsible for the Royal Naval Dockyards – Woolwich, Portsmouth, Devonport, Chatham, Pembroke, and, from 1916, Rosyth.

r3cycl3r CC BY-SA 2.0

Uncle Fred’s Metropolitan Career

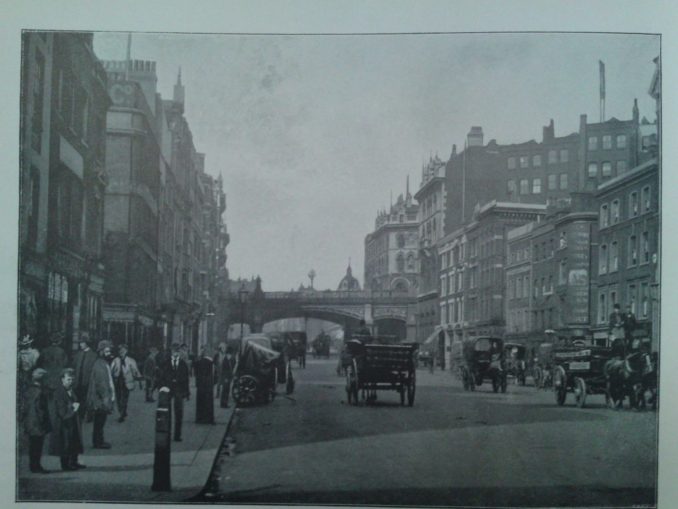

On appointment, Uncle Fred was allocated to E Division, known as ‘Holborn’.

In the 1901 Census we find him living in a police house in Grays Inn Road, along with two sergeants and eighteen constables. For those unfamiliar with the geography of London, this is in the Bloomsbury District of the Borough of Camden.

The two sergeants are aged 36 and 37 and hail from Berkshire and Deptford: the constables vary in age from 23 to 29, and come from a variety of areas, mainly in the south of England, such as Devon, Dorset, Surrey, Hampshire and London. There is one constable born in Scotland and one in India (with a thoroughly English name), but Uncle Fred appears to be the only one born in the North of England.

He appears to have stayed in the Holborn Division for at least the next 12 years, as, in the 1911 Census, he is living at 10, Holland Buildings in Bloomsbury.

At some point in the next decade, he was transferred to W Division, predominantly Clapham, and, when he retired in 1924, after 25 years’ service, he was stationed at the Rosyth Dockyard in Scotland, where he was transferred in January 1916, as one of 32 constables, 4 sergeants and an inspector.

Metropolitan Police E Division

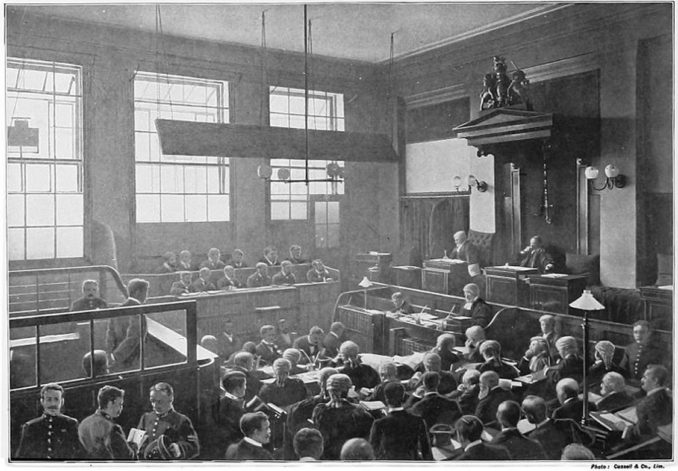

The area covered by E Division, where Uncle Fred spent at least half of his career, covered Trafalgar Square, The Strand, Kingsway, Southampton Row, Euston, Kings Cross and, importantly, The Old Bailey, which was conveniently located next door to Newgate Prison. Its location near St. Paul’s Cathedral enabled it to hear cases both from the City of London and the Metropolitan Police Divisions.

Much like today, a significant number (c. 25%) of London citizens were born elsewhere, mainly in rural areas of the UK, but there were also a variety of immigrants from the European mainland as well as large Irish and Jewish communities. It was a relatively young community, with a preponderance of women, mainly employed in service.

An examination of the Proceedings of The Old Bailey from around the time that Uncle Fred joined (1899 and 1900) shows that many of the cases tried related to the theft of possessions, which the complainant was obliged to prosecute himself. Where the accused pleaded guilty, there was no trial, and, where no evidence was presented, the accused was found Not Guilty.

There are differences in the type of theft from the cases we see today. Particularly noticeable is the number of thefts from The Post Office by employees, ranging from postal orders, through cheques to cash.

For example, Edward John Larkman (21), a postman employed by the Post Office from the age of 16, pleaded not guilty to feloniously stealing a post letter containing 4 postal orders totalling 14s. (c. £60 in today’s values). He was sentenced to Eighteen Months’ Hard Labour (and the frequent thefts at his particular post office stopped). In this case, the crime was discovered by a police constable covertly following the suspect.

Another prevalent crime we see is forgery, frequently of coins, such as Patrick Desmond (28), who pleaded not guilty to unlawfully uttering counterfeit coin. He had presented a Salvation Army Shelter with 3 counterfeit half-crowns, and revealed his guilt when asked by a constable where the 7 forged half-crowns had been spent. He replied that he didn’t know where the other 3 had gone. Following evidence from a Royal Mint Inspector, he was found guilty and sentenced to Eighteen Months’ Hard Labour.

A more sophisticated forger, Charles Twinam (54) pleaded not guilty to having instruments in his possession for hallmarking gold. He was found guilty and, illustrating how serious this crime was considered to be, was sentenced to Five Years Penal Servitude.

Crimes prosecuted by the Police also included the type of case we never see today, such as sodomy, and cases which are rare, such as bigamy, and procuring abortions: a few examples follow:-

Charles Frederick Balfour (16) pleaded guilty to bestiality and injuring a mare: he was sentenced to Twelve Months’ Hard Labour, a lenient sentence, probably because of his youth.

Joseph Johnson (25) pleaded guilty to feloniously carnally knowing Laura Shadbolt, a girl under the age of 6, and was sentenced to Three Years’ Penal Servitude, perhaps indicating how little children were valued at the time.

William Harrison (31), a Negro, was convicted of the rape of Louisa Young and assaulting and beating her: he was sentenced to Three Years’ Penal Servitude. His description (a Negro) shows how rare such individuals were.

Eliza Frances Keen and John William Smith were found guilty of feloniously causing Edith Ayres and Louisa Hooper to take a noxious drug with intent to procure their miscarriage, and Keen with using an instrument on Edith Ayres and Harriet Dadswell with intent to procure their miscarriages: Keen was sentenced to Eighteen Months’ Hard Labour and Smith to Six Months’ Hard Labour. (In cases where the woman died, the charge was Murder.)

Henry Barratt (28) pleaded guilty to gross indecency (sodomy) with Adrian Ring Picard, John Brizio, Harry Casper and Arthur Ballard, and was sentenced to Two Years’ Hard Labour. (Most of those accused of sodomy were found to be Not Guilty, but maybe four episodes was considered excessive!)

William Shin (31) pleaded guilty to bigamously marrying Alice Louisa Bartlett, and not guilty to another crime of burglary at the home of Dorothy Selwyn, a friend of his employer, which he had accessed by means of a stolen latch key. He was sentenced to Three Years’ Penal Servitude for the bigamy and Seven Years’ Penal Servitude for the robbery to run concurrently, which indicates the perceived relative gravity of the two crimes.

Various authors for Cassell & Co., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Human nature being constant through the ages, there are, of course, many cases of murder, manslaughter and robbery with violence. Where the accused pleaded guilty, no evidence was recorded. The most noticeable difference from today is the severity of the sentences of those judged to be guilty, and, especially where they are recidivists. A few examples follow.

William Wilkinson (22) and Arthur Balfour (21) pleaded guilty to robbery with violence on Mary Ann Betson. Wilkinson was sentenced to Nine Months’ Hard Labour and Balfour (with one previous conviction) Twelve Months Hard Labour, both with Twenty Strokes of the Cat.

Michael Joseph Holland (33) was charged with the wilful murder of Joseph Wootton, referred by the Coroner. He pleaded not guilty, but the victim had named him in front of a police constable before he expired. They were both drunkards and drinking partners. A number of E Division policemen were involved in the detection of the case and giving evidence to the Court. He was Sentenced to Death, but this was later commuted to imprisonment, (which frequently occurred), and he was released on licence 8 years later in 1917.

In contrast, the Death Sentence passed against Frederick James Andrews (45) for the wilful murder of Frances Short, again referred by the Coroner, appears to have been carried out, given that his date of death in Wandsworth of June 1899 was 2 months after his conviction in April 1899. The victim, with whom he lived, frequently showed signs of having been beaten, and the murder with a knife was particularly frenzied: she had been stabbed 42 times.

Aunty Sarah Lizzie

In July 1904, Uncle Fred married Sarah Elizabeth in Dewsbury: both were twenty seven years old. I have no idea how long they had been courting or where they met, but she was born in Gawthorpe (Osset), and, in the 1891 Census, at the age of fourteen, was ‘looking after the house’ for her widowed father and her brothers.

Aunty Sarah Lizzie and Uncle Fred never had children, and there was a very simple explanation for this. Although these things were never spoken about in my hearing when I was a child, my flapping ears encountered the word ‘cancer’, not that I knew what it meant at that time. I later found out that she had breast cancer as a young woman.

Although many women survive breast cancer today, this was not the case in the early 1900s, when treatment was accurately described as ‘radical’, as I shall go on to describe. Those of a sensitive disposition may wish to skip the next paragraph.

The preferred treatment for breast cancer at the time was ‘Radical Mastectomy’, which involved not only the removal of the soft tissue of both breasts, but also the underlying chest muscles and the lymph glands under both arms. Because it was believed that female hormones adversely affected the progress of the cancer, both ovaries were also routinely removed. Women frequently suffered chronic pain for the rest of their lives. Poor Aunty Sarah Lizzie! No wonder my grandmother always used the classic Yorkshire expression, “She enjoys poor health”, when talking about her.

Her medical costs would have been covered by the Met, because, otherwise, they would have been unaffordable, and, happily, Aunty Sarah Lizzie recovered and continued to ‘enjoy poor health’ until she died at the age of 89.

I was told that she was a policewoman in London, but I can, unfortunately, find no evidence of this, and, since there were no such appointments until 1919, by which time they had moved to Rosyth, it seems unlikely.

Charles Pears, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Rosyth Naval Dockyard

In 1903, in response to growing German rearmament, the Admiralty approved the construction of a new Naval Dockyard in Rosyth, and 1182 acres of land were purchased. In 1908, a contract was signed for £3 million (£400 million in today’s values) with Easton, Gibb & Son, and in 1909, construction was started on the first naval dockyard in the UK to be constructed since the days of Napoleon, on the Firth of Forth at Rosyth near Dunfernline.

Unfortunately, the Admiralty’s response was a little late, and, when war was declared in 1914, the Dockyard was unfinished. The submarine basin had been completed, but was still surrounded by its clay dam. The electricity generating and pumping stations had been completed, but there were no access roads, railways or a water supply and the main basin had still not been excavated.

The Admiralty had to make the decision to mothball the project or to accept a revised plan which would make some part of the Dockyard useable, in the event that the war was not ‘over by Christmas’. It decided on the latter course of action, and the submarine basin was useable by small craft almost immediately, with the main basin and its associated docks brought on stream by early 1916. During the course of WWI, 78 capital ships (dreadnoughts, superdreadnoughts and battle cruisers), 82 light cruisers and 37 light craft were docked and refitted.

In addition to scarcity of materials, there was a shortage of labour, and, in order to attract men from other Dockyards, a ‘garden city’ was constructed. It was a complete community with church, tea room, shops, allotments, a cinema, recreation and football fields and children’s recreation area. Although described as a ‘garden city’, the single storey prefabs were constructed from corrugated iron, but they did, at least, have running water and electric light. Locally, it was known as ‘tin town’. Only 5% of those recruited were from Scotland: the rest were from other UK Dockyards. At its height, 6,000 men were employed.

After wages were reduced at the end of the war as a result of short time working, there was a rent strike and 12 families were evicted. Despite a march of 3000 in support of the rent rebels, which Uncle Fred would certainly have policed, the striking dockers lost their homes and jobs.

The Dockyard was closed in 1925, a year after Uncle Fred’s retirement, before being reopened in 1938 on the outbreak of WWII, and it was finally privatised in 1997, when it was sold to Babcock International.

© Chrissie 2022

My Memories of My Great Great Aunt and Uncle

The 1939 Census shows my Aunt and Uncle in West Ardsley, the area of Aunty Sarah Lizzie’s childhood, living in the double fronted stone Victorian house I remember from my childhood, and I assume they must have moved there when Uncle Fred retired.

For those who don’t know the area, West Ardsley is situated between Dewsbury and Morley, (and now not far from the M62).

By the time I arrived on the scene, both Aunty Sarah Lizzie and Uncle Fred were advanced in years: Uncle Fred had a huge bushy moustache, and I used to sit for hours listening to his stories of the countryside as he whittled a stick of wood or puffed on his pipe.

They lived next door to a turkey farm, and Uncle Fred would always take me there and collect feathers for me, carving the ends to make ‘quill pens’.

My aunt looked like the Victorian lady she was, and I felt she was never keen on young children: the only time I saw her was when we had the obligatory high tea, which I recall was the most plentiful I ever set my eyes on, no doubt as a result of living in the countryside, which was always less affected by rationing.

At the time, West Ardsley was very much in the countryside, and it still hosts Lee Gap Fair, the oldest chartered Fair in the UK, having been originally granted its charter by King Stephen in 1136. It is held in fields close to my Aunt and Uncle’s house, and is now considered a mixed blessing. Originally held for three weeks at the end of August/early September, it is now confined to two days, 24th August and 17th September and all local shops and pubs are firmly closed.

Despite the many changes in West Ardsley, it still stands out as one of the few areas of countryside in the Woollen District of the West Riding.

Uncle Fred died at the age of 83, and Aunty Sarah Lizzie at the age of 89. The house is no more: it appears to have been demolished to make way for more modern housing soon after they left at the end of the 50s: the next door farm, however, is still there, although the turkeys have gone and it now deals in livestock.

I have nothing left of Aunty Sarah Lizzie or Uncle Fred, except his barometer retirement gift from the Met and Aunty Sarah Lizzie’s treasured plant pot holder.

‘The things which I have seen I now can see no more…

But yet I know where‘ere I go,

That there hath past away a glory from the earth.’

© Chrissie 2022