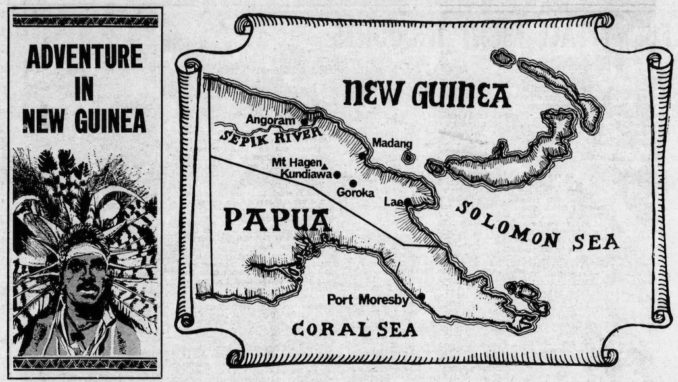

In 1969, my uncle, John Alldridge visited New Guinea to “observe the attempt to weld a primitive people to a modern society”. This is the first of his reports for the Vancouver Sun. – Jerry F

Adventure in New Guinea,

Vancouver Sun – © 2022 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

We were flying up to Mount Hagen. Thirty-four of us sitting side by side and cheek to cheek in a venerable DC3.

Not since I flew home from Belgium in 1944 with a couple of captured German generals have I travelled in such an aircraft. Nor in such mixed company.

There were wives going home to their husbands and husbands returning to their wives. There was an elderly missionary with a puckered right hand — a souvenir of a Kuku-Kuku raid 30 years ago.

There was a tribal chief in full warpaint and tall, feathered bonnet, sitting as stern as a Guards sergeant-major and as proud as Lucifer.

And there was a millionaire from Melbourne who had sold out his chain of grocery stores to go tea-planting in the New Guinea highlands — and as happy as a schoolboy let out of school.

It was hard on the buttocks. But if the ride was rough the view was stimulating.

For a while after we left Port Moresby we followed the coast around the Gulf of Papua. A desolate, God-forsaken coast: a morass of swamps surrounded by a beach of black mud, from which a few coconut palms sprout forlornly.

Down there the mosquitoes rise in clouds from reeking pools. And down there are people who live on crabs and sago. People like the Goaribaris who, back in 1901, killed and ate the famous missionary explorer James Chalmers, and have never lost their taste for human flesh.

But then we turned north and flew for nearly an hour over dense jungle, slashed open by rivers that twist and twirl in great muddy loops. Then the rain-clouds closed; and when we broke through into sunshine again we were among mountains.

Mountains such as I have never seen before. A solid, unbroken spine never less than 11,000 feet, and reaching its apex in the towering peak of Mount Wilhelm, all 14,750 feet of it.

It was those mountains and that jungle which kept the rest of the world at bay. Until the 1930s the Stone Age lingered undisturbed in the deep valleys between those mountains.

Then we were landing at Mount Hagen and the Stone Age was coming out to meet us.

A reception committee of three haughty young men, as brown as coffee-beans and — apart from tails of banana leaves hanging behind — as naked as the day they were born.

They advanced toward us. Each had a formidable war-hatchet under one arm, an umbrella slung over the other. And then they smiled that happy, unaffected smile I was to see all over New Guinea — and I knew I was welcome and among friends.

Mount Hagen, snug in a valley 5,000 feet above sea level, takes its name from the mountain that towers to 12,400 feet over it. This in turn takes its name from the Kaiser’s administrator, Count Kurt von Hagen, when this was part of German New Guinea.

Thirty years ago there was nothing here but a couple of large grass huts, used by patrol officers, and the map ended 20 miles down the road. Only there wasn’t any road.

Today Mount Hagen is the administrative capital of the Western Highlands, controlling the destiny of some 300,000 people, split up into 50 tribes and clans — many of whom have been implacable enemies for generations.

Think of the Scottish Highlands in the 15th century and you have a fair picture of the New Guinea Highlands today.

Once every two years Mount Hagen becomes world-famous for the West Highlands Show; a unique tribal get-together, an Olympic ideal, for the most primitive people on earth.

Since 1961 it has staged a two-day spectacle such as Cecil B de Mille never dreamed of; ending in a final terrifying, whooping charge of 2,000 spearmen over the hill and down into the town’s main street. It was that spine-chilling finale I had come all this way to see.

I checked in at the palatial Hagen Park Motel, which has, believe it or not, a Hungarian chef and as efficient team of native waiters as you will find anywhere, and waited for my guide.

She proved to be the very charming wife of the Administration’s principal surveyor. Janet Whish-Wilcox, originally from Tasmania, is one of 800 Europeans who enjoy life in the fresh air of the Highlands, where the days are luxuriously hot and the nights refreshingly cool.

With Janet driving the big eight-seater Peugeot we were off to explore the Wahgi valley.

The discovery of the Wahgi Valley by Michael Leahy, one of New Guinea’s “immortals,” on that April morning in 1933 is one of the most romantic adventure stories in the history of modern exploration. It has more than a touch about it of Rider Haggard and The Lost World.

The frontier then was Bena Bena, near what is now Goroka, where Leahy was prospecting the river for gold. Often he would climb to a high vantage point and look across at the clouds that hung perpetually over the mountain wall to the south.

Something about those cloud formations puzzled Leahy.

They were higher than the heavy cumulus that usually settled around the tops of a range.

“They’re the kind of clouds that rise from where there is grassland,” he said to himself; “I believe that if a man went straight through there he’d find he’d find a big valley.”

And that is just what young Mick Leahy did. It took him three months to do it. But he went straight through and found a green valley, 60 miles long and 30 miles wide, where time had stood still for 1,000 years.

A valley patterned with checkerboard gardens, tilled by a people who were skilled gardeners by instinct. Men who had nothing to learn about drainage and compost and crop rotation.

As Mike Leahy and his companions — his brother Dan and Ken Spinks, the surveyor — moved cautiously down into the valley they were met by troops of men pouring out of the tidy villages perfectly sited among the checkerboard fields. They wore bird-of-paradise plumes in their hair — blues and reds, blacks and yellows, golds and pinks. They carried spears; but spears — Leahy noticed — for thrusting, not throwing.

They approached the silvery river, which winds sedately through the valley, and the white men pointed, questioning.

“Wahgi! Wahgi!” the escort cried.

“So that’s its name,” said Mick Leahy. “Wahgi!”

And so it was to the Wahgi we were going …

I know no road more fascinating than the sixty miles of rough, red, graded gravel that runs from Mount Hagen to Minj, in the Wahgi Valley.

It leads straight out of the Stone Age into the Space Age. And in the bewildering, colourful cavalcade that passes perpetually over it you can see, if you will, not painted savages in feathers and fur but ourselves as we were before we invented the wheel.

In a never-ending stream they came up that road. Tall men with painted beards and boar’s tusks speared through their noses; in feathered bonnets that made them seem even taller. Small men with their faces blackened and noses painted red, wearing nothing but a bark-net skirt hanging from their waists, ankle-length, like a butcher’s apron.

Men carrying spears and stone axes and umbrellas. One man, stark naked except for a tuft of leaves, riding a bicycle. Another wearing a snake around his neck like a feather boa.

Women too; superbly naked under wondrous hats of parrots’ feathers, walking like queens.

And all of them going to the Mount Hagen Show; some of them walking for days at the same purposeful jog-trot.

At the first Instant Hilton we met a troupe of Kompian people. Their villages lie a hundred miles due west, over the mountains. They had been on the road four days.

Ten years ago they would never have dared to venture so far; for their route lies through the territory of old and unforgiving enemies.

Their leader was an imposing kilted figure of six feet tall; naked above the navel except for a half-moon of mother-o’pearl shell hanging from his neck and two magnificent armlets of green iridescent beetle shards, worked into a lattice of golden cane.

On his head he wore a wig of human hair, shaped rather like a Spanish matador’s hat. And in the middle of the wig was pinned his badge of office — “District Councillor, Territory of Papua and New Guinea.”

No city alderman in his robes, on his way to a Lord Mayor’s banquet, had half the dignity of that Stone Age man, delicately munching his smoking hot supper of boiled sweet potato.

The Instant Hilton — a temporary rest house built of kumai grass, eight feet wide and six feet high and a hundred yards long — was full to capacity.

Women cooked and camp fires smoked. The children settled and the warriors used the last light, to preen those precious head-dress feathers, polish spears and make final adjustments to their gear.

The men and women of the Stone Age were preparing for their Day …

Reproduced with permission

© 2022 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023