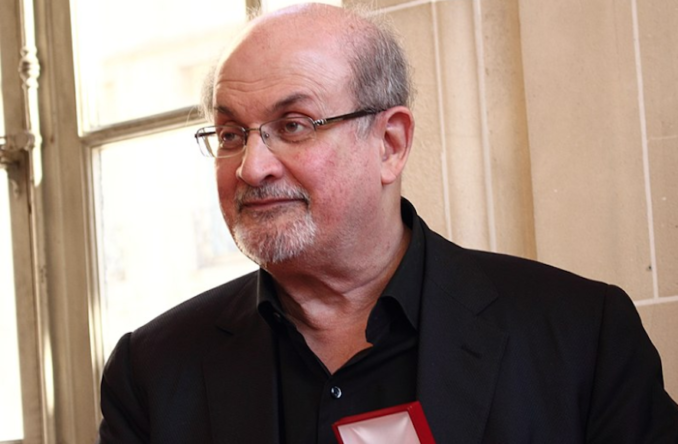

L’auteur britannique Salman Rushdie,

ActuaLitté – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

In The Beginning

Prior to sitting his professional exams, Anis Rushdie, one of the Kashmiri Rushdies, graduated from Lahore’s University of Punjab in the mid-1930s. After passing fourth overall, and as top Mulsim, Anis was despatched to England for a two years probationary period prior to a future career in the elite Indian Civil Service. However, he was in for a fall. Upon double checking his documentation, it was found he had lied about his age and had been too old to take the exams he had passed with such distinction. Mr Rushdie had falsified his age by entering his birth details on a subsequent page of a register, in a near-empty entry below the first of two twins, the second of whose record consisted only of ditto marks. Anis’s demise was to be prophetic, as written words and falls were to pass to the next generation.

Instead of leaving for India in disgrace, Mr Rushdie remained in England and successfully applied to be a research student at Kings College, Cambridge. Subsequently, he returned to India, settled in Bombay, married school teacher Hegin Batt and rose to be a lawyer, businessman and wealthy landowner. On 19th June 1947, only weeks before the Indian subcontinent was partitioned and the resulting states gained their independence from the British Empire, Anis and Hegin were blessed with a son, Ahmed Salman Rushdie.

In the cosmopolitan mega-city, Salman Rushdie attended the exclusive Cathedral and John Connon School, motto ‘Studies Makes Famous’. Contemporaries describe him as a regular prize winner who was exceptionally clever, had a flair for words and a gift for storytelling and writing. His penchant was wordplay, allegory and metaphor. English master and mentor, Owen Glynne-Howell, stated Rushdie to be one of the brightest pupils he’d ever taught.

The school bully, however, recalls Salman as spoiled and effete with pink cheeks and white seersucker shirts. Practical jokes played upon the young brainiac included watching his fountain pen melt upon being filled from an inkwell laced with sulphuric acid. All agree Rushdie was not sporty. After Cathedral School, when a boarder at Rugby School in England, the great author described himself as ‘clever, foreign and bad at games.’

After Rubgy, Salam followed in his father’s footsteps to Kings College, Cambridge, where he graduated in history and was a member of the Cambridge Footlights theatrical company. After graduation, he returned to live with his family, by now resident in Pakistan, but in 1964 returned to London and partway through attempting to establish a career in acting which was destined to travel no further than the London fringe, he took a position with advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather on the recommendation of a friend.

There, his expertise in wordplay and metaphor came to the fore. As an advertising copywriter, he is credited with making Aero bars ‘irresistibubble’, insisting American Express transactions will ‘do nicely’ and anointing cream cakes, ‘naughty but nice.’ In the ten years between 1970 and 1980, he wrote in his spare time, in the same near-surrealistic word and image association style used to grab the attention and put across persuasive value-loaded messages in thirty-second commercials.

His style has been described as surreal, allegorical, mystical, effusive, melodramatic, magical-realistic, satirical. Certainly, the style of the precocious child, gifted in wordplay and familiar with the realty bending techniques of the advertiser.

His first published work was called Grimus and was published in 1975. The Sunday Times described it as a “ramshackle surreal saga based on a 12th-century Sufi poem and copiously encrusted with mythic and literary allusion [which] nosedived into oblivion amid almost universal critical derision.”

Rushdie persisted with the same style but told a better story more accessible to critics and public alike with his 1980 smash hit and Booker Prize-winning Midnight’s Children. This tells the tales of magical, blessed and gifted children (a bit like Rushdie himself) born at midnight on 14th August 1947, just as India became independent.

This reviewer has read the book and half enjoyed it while slightly less than half understanding it. I can recall the protagonist’s special power was a giant nose allowing him to join the Pakistani army as a bloodhound. An important message is hidden in there somewhere no doubt. Suffice it to say, satire within satire within satire told mystically, went way over this reader’s head but contained within the metaphor was sufficient offence for the book to be banned in India and for London critics and literati to absolutely love it.

His third book was Shame. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize, banned in Pakistan. The fourth, a non-fiction work, Jaguar, about Nicaragua. His fifth published book was another work of magical realism, infamously called The Satanic Verses, which resulted in a fatwa being placed upon him and, 33 years after publication, the recent murder attempt which sees 75-year-old Rushdie on a ventilator in an Erie Pennsylvania hospital.

So why is The Satanic Verses so offensive and why is it so named? Offensive because the book re-writes the Koran and conflates Allah with the Devil. So-called because of its references to the Koran’s Surah (Chapter) 53, verses 19-22.

Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses

The book begins with an explosion on an aeroplane approaching England. Two passengers, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chancha, both Indian actors, are falling to earth. Gibreel is the Indian form of ‘Gabriel’. In Islam, Judaism and Christianity the Angel Gabriel is the messenger of God. In Christianity, it was Gabriel who, among other things, announced the Blessed Virgin pregnant. In Islam, Gabriel revealed the Koran to the Prophet Mohammed.

The plane exploded at an altitude of 29,002 ft – as if the height of Everest. Therefore, Gabriel rather than being an angel from heaven is not only human but a human experiencing the biggest earthly Fall possible. Meanwhile, back in India, Rehka Merchant, Gibreel’s recently abandoned mistress, is throwing herself and her children off the top of Bombay’s Everest Villas apartment block. As she dies, she leaves her earthy form and is able to visit Gibreel in the shape of a cloud as he continues his descent to earth. Cursing him, scorning him and damning him to the Devil she sings in an ancient tongue the only word of which Gibreel is familiar with being ‘Al-Lat’.

Therefore, not only is Gibreel, bringer of the Holy Koran to mankind via the Prophet Mohommed, portrayed as a fallen man but also as an agent of Satan. This theme recurs through the book and is blasphemous within Islam.

And so it continues. Back in Bombay, not only is film star Gibreel missing but his movie posters begin to rot and his image disappear. Even the celluloid on his films bleaches, removing his image from view. There are two important references here. Firstly, the taboo about earthly representations of important figures in Islam (eg the Charlie Hebdo cartoons) and secondly the suggestion that the believer’s subsequent impression of the bringer of Allah’s intention is based upon ignorance.

Again, these suggestions are blasphemous.

In flashback, as he falls, we learn the potted biography of Gibreel which mirrors the early life of the Prophet Mohammed. His fleeing and exile between cities. His being an orphan raised by an uncle. Conflating the Prophet and the Angel Gabriel suggests Mohammed authored the Koran himself rather than being dictated to by Allah. More blasphemy.

View of Mecca in 2012,

GLady – Licence CC BY-SA 1.0

In a dream sequence, Gibreel goes back in time and visits a desert city made of sand, obviously meant to be Mecca. Rusdhie mocks the washing rituals of the inhabitants, allocates new occupations to the Prophet Mohammed’s wives and names their ‘establishment’ in a way which belittles Islamic female coverings. On a hillside nearby, he meets with the Prophet Mohammed who he names ‘Mahound’, an offensive name which has its origins in the Medieval Christian belief of Mahommmadens as devil worshippers. It also contains the word ‘hound’ which clever wordplay expert Rushdie must have known will offend as it suggests the unclean animal that is the dog.

The Prophet confides to Gibreel that he is experiencing difficulty in converting the people of the desert city. The pair of them hatch a plan whereupon a compromise will be allowed where three of the 360 municipal gods will continue to be worshipped in the new monotheistic religion of Islam. This brings us to the Koran’s Satanic Verses.

The Koran’s Satanic Verses, Surah 53, Verses 19-22

As well as Christians and Jews, early Islamic scholars were familiar with the possibility of a prophet being a flawed soul conducting an ongoing struggle to reveal difficult and often unwelcome truths. However, in later Islam, the idea of the perfection of Mohammed emerges via the concept of “ismat al-anbiya”. Literally meaning ‘the protection of the prophets’. This attributes infallibility to prophets, imans and angels and declares them free from sin and error.

Given the difficulty in contradicting early scholars referencing a ‘Satanic’ version of the 53rd Surah, there lies an assumption this was the original text. Ibn Ishaq is credited with the first biography of the Prophet Mohammed. Although his work is lost, it was used by a later writer, Ibn Hisham, who conceded the existence of the controversial verses by stating he was omitting them as they cause offence to some. Subsequently, the verses are quoted by al-Tabari and other early scholars such as Ibn Sa’d and Al-Waqidi.

In our examination, we shall use Sir William Muir’s 1878 work The Life Of Mahomet From Original Sources for translation and commentary as, to the Western mind, this provides an understandable interpretation of events. Mahomet is another name for the Prophet Mohammed. As for Sir William Muir, he was an orientalist, colonial administrator, Principle of the University of Edinburgh and a one-time Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Provinces of British India. His translation of Surah 53:19-22 reads:

And see ye not Lat and Ozza,

And Manat the third besides?

These are exalted Females,

And verily their intercession is to be hoped for.

Lat, Ozza and Manat are the three old Meccan gods. Lat being the Al-Lat referred to in Gibreel’s fall, appropriately but blasphemously revered as an idol of jealousy and infidelity in some parts of the Middle East. Palmyra in Syria was rich in monuments to Al-Lat but many were blown up as recently as 2015 when the area was occupied by Islamic State during the Syrian Civil War.

The Arabic word Muir translates as ‘exalted females’ is gharāniq which literally means crane or high soaring bird. It only occurs once in the Koran (a hapax legomenon) making it hard to translate via context. Given the mention of Ozza, Lat and Manat and that ‘females soaring high’ are the opposite of a Fallen man, one might prefer a contextual translation of ‘Goddesses’.

In the final line, ‘intersession’ is a straightforward concept for Christians, it being prayer offered to God through a saint. But extra gods and intersession are blasphemous in Islam. So why did the Prophet Mohammed proclaim these verses? In his commentary Sir William comments,

“When he had reached this verse, the devil suggested to Mahomet an expression of thoughts which had long possessed his soul; and put into his mouth words of reconciliation and compromise such as he had been yearning that God might send unto his people.”

Sir William tells us after hearing the poly-theistic compromise, the Meccans were delighted and astonished, prostrated themselves, and worshipped in the new faith. However, that evening, the angel Gabriel visited the Prophet Mohammed and admonished him saying, “What is this that thou hast done? thou hast repeated before the people words that I never gave unto thee.” Sir William continues,

“So Mahomet grieved sore, and feared the Lord greatly; and he said, I have spoken of God that which He hath not said. But the Lord comforted his Prophet, and restored his confidence, and cancelled the verse, and revealed the true reading thereof.”

To this day, the Surah now reads (Muir’s translation again);

And see ye not Lat and Ozza,

And Manat the third beside?

What! shall there be male progeny unto you, and female unto Him?

That were indeed an unjust partition!

They are naught but names, which ye and your fathers have invented…

Therefore the extra gods are cancelled and the concept of intercession is removed. However, Sir William notes the two Satanic verses were now in the mouths of all the unbelievers, increasing their malice towards the believers and stirring them to persecute the faithful with greater severity. Sir William explains the resulting and continuing dilemma:

“Pious Mussulmans of after days, scandalised at the lapse of their Prophet into so flagrant a concession, would reject the whole story. But the authorities are too strong to be impugned. It is hardly possible to conceive how the tale, if not in some shape or other founded in truth, could ever have been invented.”

Besides the commentary of the early scholars, Muir also notes refugees from pre-conversion Meccan persecution returned to the city from exile in Abysinnia, something not possible unless a ‘compromise’ Surah had converted all of Mecca. However, Rushdie sticks a knife into every side of the argument by, in his fictional work, claiming Gibreel tells Mahound that he dictated both versions as if on behalf of both the Devil and Allah.

“It was me both times, baba, me first and second also me.”

In a more contemporary commentary, Analysis of Salman Rushdie’s Novels, Nasrullah Mambrol concludes of Rushdie’s Satanic Verses:

“One can draw implications that Islam was founded by rationalizing good and evil, that its founder was both a sincere mystic and a power-hungry entrepreneur, and that Gibreel, an actor who specializes in impersonating deities, had given at least one bravura performance that changed history.”

Mambrol also tellingly observes,

“What is clear is that The Satanic Verses is the logical sequel to ideas Rushdie began to develop in Midnight’s Children and Shame, as well as an allegory that strains narrative and religious sensibilities to the breaking point.”

Breaking Point

The Satanic Verses was published on 26th September 1988 and was well received with little initial scandal apart from being banned in secular India (after pressure upon Rajiv Gandhi’s government from the Janata Party) but not in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. A calm before the storm. While promoting the book the following month, Rushdie spoke with Ciaran Carty of Dublin’s Sunday Tribune under the headline Rushdie To Judgement. The interview began with Rushdie casually claiming he made no apology for re-writing the Koran (a work which by divine command cannot be changed).

“There are no subjects which are off limits in fiction and that includes God, because if you say there are limits, who sets the limits?” He somewhat naively impugned. In those days, the world was still at the point where a pile-on consisted of telegramming Indian embassies asking customs restrictions be lifted on controversial books. Rushdie confided his biggest irritation was the English getting his name wrong. It’s Sal-man, not Salman, and Rooshdie, not Rushdie. The author insisted his work was about the immigrant and transformation but, as he spoke, other interpretations were emerging and a storm gathering. Ominously, the reason it hadn’t been banned in Pakistan, this being in the days before 24 rolling news and the internet, was because they hadn’t found out about it yet.

By late October Rushdie was having to cancel trips and use a bodyguard. By the end of November, the novel had been banned in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Somalia, Bangladesh, Sudan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Qatar. In December, 7,000 Muslims attended a book-burning rally – in Bolton. The novel didn’t arrive in the USA until February 1989 by which time news had reached Pakistan with 6 killed and 100 injured in an attack on the American Cultural Centre in Islamabad. More were killed and injured in riots in Jammu and Kashmir.

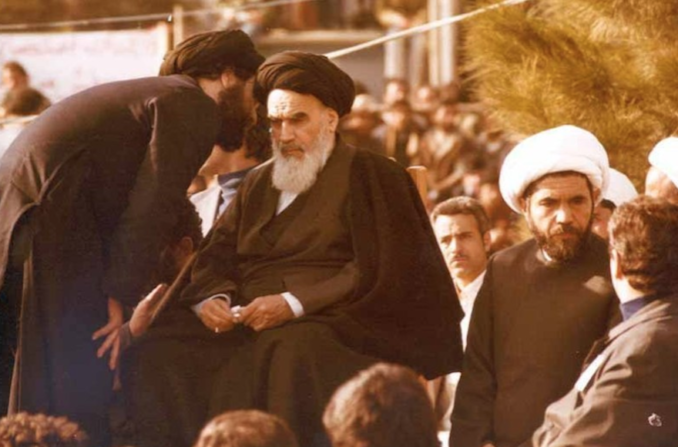

Ayatollah Mohammad Mofatteh and Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini,

Unknown photographer – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

On St Valentine’s Day 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa on Rushdie calling upon Muslims to execute everyone involved in the publication of the novel. Rushdie went into hiding on the same day, with Martin Amis waggishly observing the author had vanished into block capitals on the front page of every newspaper in the world. Eventually, the bounty associated with the death sentence was to reach $6,000,000. By March, Iran had broken diplomatic relations with Britain and many bookstores had withdrawn the book.

Since then, Cat Stevens has supported the fatwa, Hitoshi Igarashi, the novel’s Japanese translator, has been stabbed to death and Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator, has been seriously wounded. Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie has worried about the offence caused to followers of Islam. Labour’s then Deputy Leader Roy Hattersley, called for the paperback version to be withdrawn. Shirley Williams, then of the Liberal Democrats, said protecting Rushdie was “a waste of taxpayers’ money” and his subsequent knighthood was “a mistake”. And so on and so forth. The late Christopher Hitchens quipped the saga had become as bizarre as a bad Salman Rushdie novel.

While hiding and living under an alias, Rushdie continued to write, win awards and be lauded. In 2001, and by now resident in the United States, he partially dropped his exile and began to make an increasing number of public appearances. Although the Iranian government subsequently dropped its intention to enforce the fatwa, a fatwa is a religious decree and remains in place. As recently as 2019, Rushdie was still being accompanied by an armed police guard during press interviews.

On August 12th 2022, state troopers were present at his lecture in the Chautaugua Institution in Chautaugua, New York, but were unable to prevent a man from rushing onto the stage and stabbing Rushdie repeatedly about the head, neck and abdomen. At the time of writing, Salman Rushdie is said to be on the ‘road to recovery’ but freedom of speech, in an age of instant mass communication and a violent Muslim response to blasphemy, treads an uncertain path.

Selective References & Suggested Extra Reading

Nasrullah Mambrol, Analysis of Salman Rushdie’s Novels

Sir William Muir, The Life Of Mahomet From Original Sources (selective quotes)

The Guardian, Summary of Reprisals Post-1988

Wiki, The Sinless Prophet

Wiki, Satanic Verses

© Always Worth Saying 2022