© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

The above photograph was taken on March 25th 1936. How can we be so certain? The marquee to the left can be seen at the beginning of a video clip below, the occasion being the leaving of the Clyde of the RMS Queen Mary which sits in the background. By the miracle of Street View, 86 years later we can stand beside the very same fitting-out dock of the former John Brown & Company’s shipyard at Clydebank and observe the same square latticed cantilever Titan crane to the left of the QM.

The forest of spindlier cranes to the right work the slipways where vessels were assembled until float-worthy, whereupon they would be launched and moved to the fitting-out dock.

The QM herself had been launched on 26th September 1934 by Queen Mary. The vessel was a mighty 80,774 gross registered tons, 1019 feet in length and was capable of developing 200,000 ship horsepower. Twelve decks accommodated 2,140 passengers. Her draft of 38ft and 9 inches required parts of the Clyde to be deepened to allow her passage from the yard.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

At the time of the launch, the little chap standing in front of her would have been just shy of two years old. Eighteen months later, the Queen Mary completed, we see him well wrapped up for a west of Scotland spring day. Crouching in front of him taking the photograph would be my grandfather Elihu who, as we found out last time, was an agricultural mechanic, by now aged 30.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Queen Mary was about to begin the most difficult and dangerous journey of her 31 years at sea. Although oblivious to the necessity at the time, with a maximum speed of 33 knots, she could easily outrun a U-boat and torpedo but could she escape from Clydebank?

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

A breathless Pathe News reporter later informed startled cinema audiences that the vessel had that day embarked upon,

“One of the greatest feats ever attempted by British pilots.”

He continued,

“The most ticklish voyage of her whole career lies between this point and the sea, fifteen twisting miles of the River Clyde with a centre channel so narrow that if she swings more than a few yards off her course she’ll strike mud banks and so shallow that at some points she’ll be less than ten feet between her keel and the river bed.”

Those twists and turns included the notorious river bends at Dalmuir and Bowling with several tugs required aft, forward, port and starboard to nudge her seawards at walking pace. Close on one million sightseers lined the route with, by the end of the day, the Queen Mary being safely at anchor off Greenock.

Originally laid down in 1930, economic problems resulted in a type of furlough with production being stopped and started again, with government assistance, on condition owners the Cunard Line merged with the struggling White Star Line.

At the beginning of the above video clip we can see picture one’s marquees as the QM sits in the fitting-out basin at John Brown’s. Later, we follow her stately progress along the perilously shallow and bendy Clyde as nearly a million well wrapped up Scots line the river banks.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2022

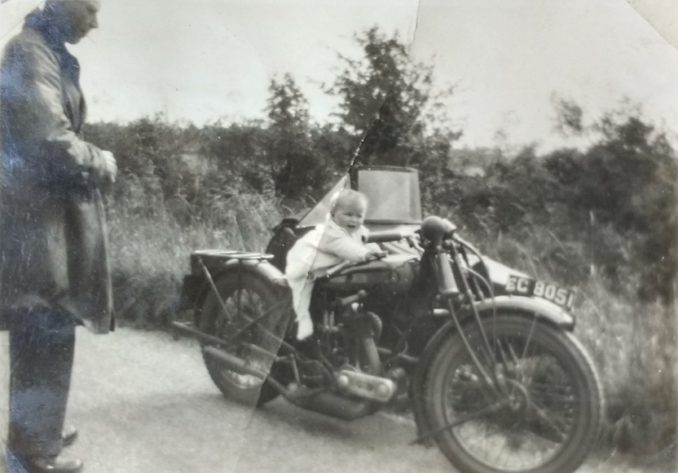

As for how my father and grandparents got there, it doesn’t bear thinking of but there is evidence, dated 1933, of motorbike and sidecar. A two hundred mile March round trip to Clydebank before the motorway had been invented sounds daunting but probably less so than Hause to Howtown, before a tarmac road connected the two and with an apparently grumpy toddler in the sidecar.

No need for crash helmets.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2022

The motorcycle, seemingly being admired by King George VI, is a Triumph Model N, a 1928 500cc machine that retailed for £36. The EC observable on the ‘pedestrian slicer’ registration plate was the local authority regional code for Westmoreland.

Previously, Elihu had a 1929 Calthorpe Ivory but married life and a young son must have seen an end to that. As further proof that not much changes, 65 years later, in anticipation of Elihu’s first great-grandchild, your humble reviewer of old photographs spent a sobering day behind the wheel of his pride and joy touring the car lots looking for something with an engine half the size, two extra doors and a boot that could hold more than a spare wheel.

On a more serious note, seven years after her thankfully uneventful river trip to Greenock, my grandfather would meet up with the Queen Mary again – in very different circumstances.

***

His ship photographs began four years before the Clydebank caper, in 1932, with a picture of the Britannic and Georgic in Liverpool.

Elihu had a family connection with the Mersey port as his older brother (two sisters having been born between them) moved there from rural Cumberland, married and had a son also called John. We shall imagine the cousins (ten years separating them) excitedly down at the docks watching the big ships. Elihu, for a while perhaps, compensating for the father that John never had.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

John senior had married in May 1916 and enlisted in the 10th King’s Liverpool Scottish Battalion. In 1917 he was wounded in action and on the 14th April of that year was discharged as no longer fit for service. He returned to Liverpool and died there on 16th June 1917, aged only 27. His war grave sits in West Derby Cemetery. At the time, John junior was only two months old.

Returning to the above photograph, note the lighter shade of funnel compared to the Queen Mary. Those are the colours of the White Star Line prior to its merger with Cunard.

MV Britannic was launched in 1929 as the penultimate pre-merger White Star liner. A 683 ft long vessel, she carried over 1,500 passengers in three classes, was built at Harland and Wolfe in Belfast and made her maiden transatlantic voyage in 1930 on the Liverpool to New York run. From 1935 she was used on the London − Le Havre − Southampton − New York route. During the war, Britannic was a troopship after which she returned to the peacetime Liverpool/New York run until 1960.

Scrapped in 1961, she was the last survivor of the former White Star Line.

Her sister, Georgic, was also built by Hardland and Wolf and had a similar early career on the Liverpool and London to New York runs. Also used as a troopship, she was bombed and sunk on 14th July 1941 off Port Tewfik (also known as Port Tawfiq, now known as Port Suez) close to the Suez Canal’s Gulf of Suez southern entrance. Salvaged and rebuilt, she resumed as a troop transport. Post-war, Georgic worked both UK to Australia and transatlantic crossings before being taken out of service and sold for scrap in 1956.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Also in Liverpool in 1932, HMS Exeter was alongside with awning rigged to aft, presumably to entertain visitors. One of two York Class cruisers, Exeter was built at Devonport and launched on the 18th July 1929. She weighed 8400 tons, was 540ft long and had a peacetime compliment of 628. Her main armament consisted of three twin eight-inch guns.

In a retrospective piece, The Liverpool Evening Express of the 14th December 1939 recalled the occasion.

She visited Liverpool in June 1932, in command of Captain I W Gibson and during her stay many thousands of people inspected the ship. Entertainments were arranged for the crew, and the Lord Mayor of Liverpool (Alderman J.C. Cross) gave a dance for the officers at the Town Hall.

In a potted biography, the Express goes on to tell its readers that Exeter had been commissioned into the Second Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet the previous year and during 1936 had returned to this side of the Atlantic to reinforce the Mediterranean Fleet. Returning to West Indies Station the following year, alongside HMS Ajax she had helped to quell riots in the Trinidad oil fields. In 1938 Exeter had completed an 80,000-mile [8,000?] cruise covering all of the major ports on both seaboards of South America and had continued along the west coast of the continent all the way to British Columbia.

Earlier in 1939, Exeter assisted the survivors of an earthquake in southern Chile.

Of course, The Liverpool Evening Express’s reminiscences weren’t by chance. The day before publication, as part of the Navy’s South American Division, Exeter had engaged the Graf Spee during the Battle of the River Plate. Sixty-one of her crew were killed and twenty-three wounded.

After repairs, Exeter headed east on Indian Ocean and Singapore escort duties. Crippled during the Second Battle of the Java Sea during the last naval action of the Netherlands East Indies campaign, on 1st March 1942 the ship was abandoned and scuttled with the Japanese rescuing 652 of the crew, 152 of whom died in captivity.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2022

At the outbreak of war, my grandfather had volunteered and, being a whizz with machinery, found himself in the Royal Army Service Corps. Sent to Aldershot, he was a dispatch rider’s dicky Royal Enfield’s test run from Southampton where he could indulge his interest in big ships, including a reunion with Queen Mary pictured above.

However, as we shall see next time, our family’s very own phoney war was not to last. Tragedy was steaming towards us via a very distant shore.

© Always Worth Saying 2022