© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

The above photograph appears in our family Nostalgia Album captioned “Mauretania Southampton 1939”. Although every Big Boy’s Big Book of Big Ships says something different, the photograph, languishing in the Worth-Saying family album for 83 years may be unique, even historically significant. It might even be worth a bob or two. The vessel in the background is the Queen Mary, identifiable because it looks like the Queen Mary and because another album photo, shown in last week’s episode, is a close up of the QM taken on the same day after a brief walk around the docks.

If you think Mauritania looks brand spanking new that’s because she is. Launched on 28th July 1938 at Cammell Laird, Birkenhead, the 35,000 ton (half the size of the Queen Mary) Cunard liner made her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York via Cobh, Ireland, on 17th June 1939. A journey of 5 days 21 hours and 22 minutes.[1] Originally she carried 1,360 passengers and had a crew of 802 and at the time was the largest ship ever built in England, the bigger ‘Queens’ having been built on the Clyde.

After only two months on the transatlantic run, news that Germany had invaded Poland was forwarded to the Mauritania in mid-Atlantic along with the order to make for Southampton, not Liverpool, and to omit the call at Cobh. According to the Liverpool Ships website, she arrived at Southampton on September 3rd, the very day that war was declared.

I would love to be able to tell Puffins that my grandfather, quick off the mark to volunteer (which he was) rendezvoused with the liners down at the docks at Southampton having been stationed to nearby Aldershot (which he was) while gold bullion, Bob Hope and a record 2,500 passengers were squeezed onto the Queen Mary to escape the conflagration that was about to consume Europe. Having blagged his way to the dockside, using his IAE pass and a blurry Debatable Lands to Hampshire travel warrant, he snapped a unique photograph now worth millions.

Unfortunately, according to wiki, the Queen Mary, the bullion and Bob Hope set out for New York on 1st September, missing Mauritania by three days. An interesting and possibly unique snap all the same as, between June and September 1939, one wonders how many times the two liners were in the same place at the same time.

After her September voyage, the QM was painted battle grey and converted to a troopship in America. Similarly, over here, Mauretania was requisitioned, armed with two 6-inch guns, given her wartime colours and sent back to America in December 1939.

The British liner RMS Mauretania docks,

US War Department – Public domain

Also used as a troopship during the war, Mauretania initially served Australia, Suez, India & Singapore. Later she was used in the North Atlantic and finally the Pacific. In all she travelled 540,000 wartime miles and carried over 340,000 troops. After the war, she spent a year repatriating troops and civilians before being returned to Cunard to be used as a relief passenger liner covering the Queen Mary’s and Queen Elizabeth’s spells out of service. As the transatlantic liner market declined, she took to cruising around the Med and was finally taken out of service in 1965 and scrapped in 1966.

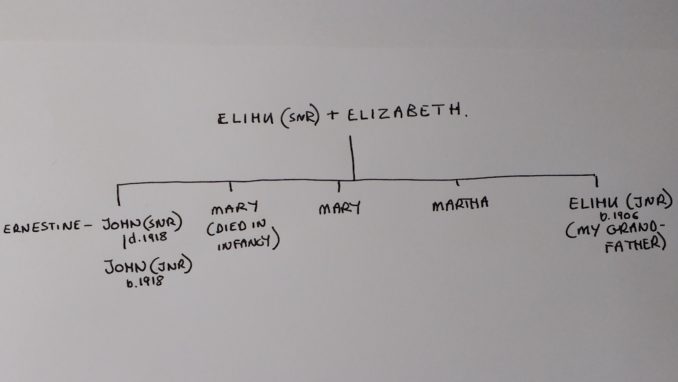

Although 1939 was ending badly, 1938 had ended on a brighter note. Our local newspaper reported, next to the foxhound dates and the startling news that £800 was to be spent bringing mains water to Penrith, my great grandparents Elihu Senior and Elizabeth were to celebrate their golden wedding on Christmas Day 1938. Elihu Snr had been born on the farm, moved to the city and worked as a grocer for various employers, one for 42 years, before retiring aged 77. The article lists the happy couple’s ‘surviving children’ as my grandfather (Elihu Jr) and his two older sisters. There is no mention of a third daughter, Mary, who died in infancy. Later the article referred to,

“… another son, Jack, who served his apprenticeship with Messrs Oram, provision merchants, [who] died in Liverpool some years ago.”

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Last time we learned that Jack, Christened John, died just after the First War. I am grateful to Puffin Captain Slugwash who, following last week’s instalment, put himself and his best matelots into a couple of ship’s boats, dropped over the side of the Black Pig’s sister ship and set off for some fruitful foraging. During which it was discovered John had joined the King’s 10th Liverpool Scottish Battalion in 1913 and would have been one of the ‘Maidanmen’ who was sent to France early in the war on in the SS Maidan.

As such he was entitled to the 1914 star earned by as few as 26 territorial battalions with only the better Territorial Force units having been initially sent to France. In his dispatch, Captian Slugwash notes,

“Being discharged in April 1917 it is fairly safe to assume that he was wounded or found medically unfit in the Spring of 1917. There were no major actions at this time, the 10th holding the line in the Ypres Sector, so it is probable that he was a victim of the daily grind of trench life. The battalion war diary and Gilchrist’s book mention almost daily victims to shelling etc whilst in the line, but rarely mention the names of other ranks.”

“Finally, if you were not aware already, the Liverpool Scottish was quite a stylish battalion. Many of the other ranks were of high social standing, and most of the original men who made it through to 1917 were usually Commissioned.”

Captain Slugwash recommends Bravest of Hearts by Hal Giblin, a biography of the Liverpool Scottish in WW1.

The documents forwarded by the foraging party show John was disembarked on 1/11/1914, was discharged medically unfit on 14th April 1917 and died on the 16th June 1918 ‘of sickness’. His widow Ernestine received £13 and 10 shillings. He was 27 and left a son, also John, aged only 2 months.

The Territorial Force Records Office classified the discharge as “W392 XVI KR”. KR means Kings Regulations. Section 392 covers a multitude as does sub-section xvi. ‘W’ stands for wounds, as opposed to ‘S’ (for sickness). The neighbouring entries on the records show the steady trickle of casualties accurately surmised by Captian Pugwah as the ‘grind of trench life’. Although John’s war grave isn’t in our family album, a loose print sits in the family deed box.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Captian Slugwash also forwarded John and Ernestine’s marriage certificate which shows her maiden name to have been Burnell. They married in 1916, presumably when John was on leave. Further investigation shows that Ernestine had a sister, Gwendoline, who married in similar circumstances in October 1915. Her husband, 2nd Lieutenant William Douglas Sadler of C Company 9th Bn The East Surrey Regiment died in Ypres of wounds received at Klein Zillebeke on 3rd August 1917. He was 23.

As a measure of the mixed fortunes of war, a cousin of Ernestine and Gwendoline was a decorated war hero awarded the Military Cross and invited to meet the King at Buckingham Palace. William Burnell May served with the Royal Fusiliers and the York and Lancaster Regiment. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of Wednesday 15th January 1919 takes up the story.

“Sec Lieut William Burnell May 2/4th Batt Y and L Regt TF. He led his platoon through a heavy barrage, and coming under machine-gun fire at point-blank range, he showed a fine example of courage and leadership and rushed two machine-guns, killing their teams. he reorganised his platoon and advanced in spite of being wounded himself. His prompt action and able leadership undoubtedly saved many casualties, as the battalion was able to advance without interference of fire from the rear.”

***

His elder brother John having been killed in World War One, my grandfather Elihu Jnr was quick off the mark in volunteering as the world headed to war again.

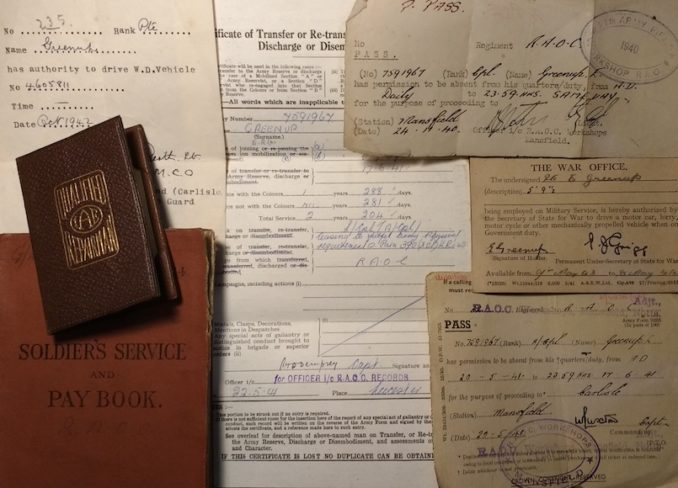

In a previous episode, posing with his 1920s motorbikes, we found him as an agricultural engineer. In May 1938 he qualified as an Institution of Automotive Engineers repairman having completed their practical tests, written examinations and been able to provide “a report regarding his capabilities and character from his present or late employer”.

As such he was issued with an Institution of Automotive Engineers (established 1906, incorporated by royal charter 1938) certificate, pocket certificate and was allowed to wear their silver badge “as an indication to the public of the competency of the wearer.”

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

From a small collection of papers in our family deed box, we can piece together his service. In November of 1938, Elihu enlisted in the Supplementary Reserve of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (not the RASC as I mistakenly informed Puffins last time) and was therefore, according to his Army pay book, mobilized to the colours on the 1st September 1939.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

His pay book describes my grandfather as being 5’9″ and 10 stone 13lbs. Looking older than his 33 years, his medical condition is rated as C but raises to B1 by mid-1940. In July 1940 he is classified trade tested by an officer of the 1C Fitter’s School in Aldershot and declared an A1 fitter. Judging by subsequent travel passes, he was sent to the 11th Army Field Worksop near Mansfield. 11th AFW were part of the order of battle of the unsuccessful 1940 British Expeditionary Force to France, later evacuated from Dunkirk and nearby ports.

In May 1941, about the time of Dunkirk, Elihu was discharged from the RAOC for “ceasing to fulfil the army’s physical requirements”, again under Kings Regulations 390 this time marked enigmatically ‘XOP’. The medical dictionary suggests this to be an outward deviation of the eyes but family history recalls he became profoundly deaf, presumably while working with machinery in the days before ear protection. Softening the disappointment, according to his Certificate of Discharge, he was given a good send off from the corps. His superior officer noted,

Very good during his one year and eight months service with the colours. A conscientious and fully competent motor vehicle fitter.

Back home, Elihu joined the Home Guard with his permissions showing that he made himself useful by driving War Department vehicles.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

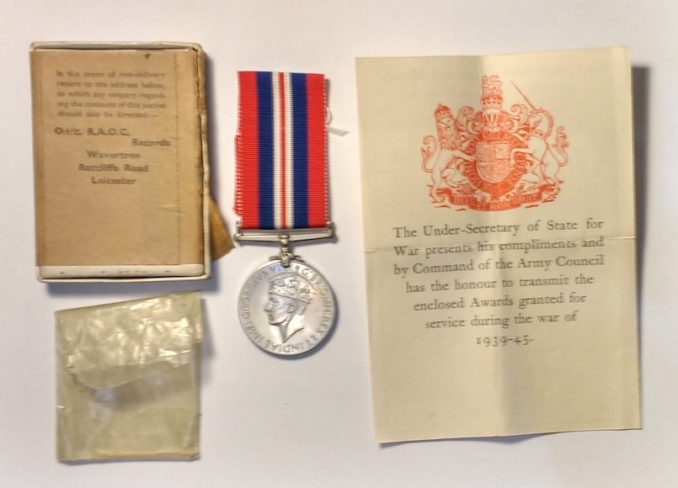

After the war, the RAOC sent my grandfather his 1939-1945 service medal. However, it sits in the family deed box as if discarded. Still with its foil wrapper, it looks as though it has never been out of the box let alone worn. There are no pinholes through the ribbon. A modest man, one assumes he felt it undeserved when compared to the sacrifice of his elder brother John and many others.

Elsewhere my grandfather’s nephew, John junior, who never knew his own fallen father, had also volunteered. We shall follow his story next time.

Acknowledgements

Further thanks to Captain Slugwash

[1]http://ssmaritime.com/RMS-Mauretania.htm

© Always Worth Saying 2022