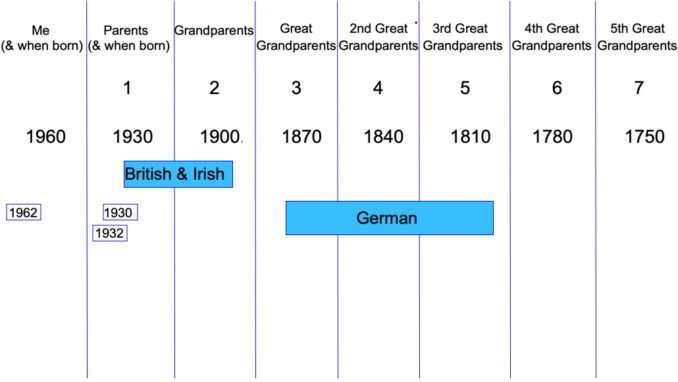

In part one of this odyssey into the past, you’ll recall me being curious and excited in anticipation of the results of a Christmas present DNA test: Who Do I Think I Am? In part two, tellingly subtitled Not Who I Think I Am, I shared with Puffins the puzzling result that showed me 20% German. Having discounted the distant influence of Anglo-Saxons and Elizabethan Lake District German miners, I was left with a bewildering array of previous generations none of whom at first glance, or after further examination, appeared to have any connection with Germany.

There is a truism which says that if things become too complicated, the answer will be the simplest explanation. Back to basics, make another, blank family tree and start again at the beginning.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

The genes app provided a timeline suggesting my most recent German ancestor might be a great-grandparent born in the late 19th century. I know the names of my eight ancestors of that generation. All are English or Scottish sounding (I live close to the border). All were born in the extreme northwest of England or southwest of Scotland except one who was born in the West Country and came to our Debatable Lands after being posted to a local regiment.

On my mother’s side, second cousins are also on the app and show no trace of the Germanic. The focus turned to my father who, helpfully in these circumstances, did look like a German. Both he, myself, my daughter and my youngest son are blue-eyed and had giveaway bright blond hair when small. On my father’s side, the four great-grandparents are a Worth-Saying (obviously), a Westmorland Glendinning, a Thwaite (respectable Buttermere farmers) and a Brice (the military type, I have his medals from Waziristan).

During my back-to-basics trawl, a gap hid in full sight between the leather-bound covers of my paternal grandmother’s photo album. Ordinarily a harmless depiction of prewar holidays in North Wales and pictures of old motorbikes, the images included an omission (if you see what I mean). The centre of the album’s inside front page shows my paternal grandfather and grandmother pictured on or close to their wedding day. Surrounding them are photographs of the previous generation.

But where the Glendinnings should be, sits a very old photo of the previous generation of Worth-Sayings, John and Anne, clothes held together with twine. John is the one who lost half the family farm on a crackpot scheme (in cahoots with a cad called the Duke of Northumberland) to build an 1860s Railway Mania iron road from nowhere to nowhere. Not to worry, he worked the surviving half of the farm evenings and weekends and toiled in an iron ore mine through the day.

All well and good, but why are they occupying a space that should be taken by my great-grandmother’s parents, the Glendinnings, a farming family of Brampton in the Eden Valley part of Westmorland? There is an obvious explanation. As every schoolboy and Puffin knows, and despite what the French may misinform you of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, photography was invented by Englishman Henry Fox Talbot in 1834.

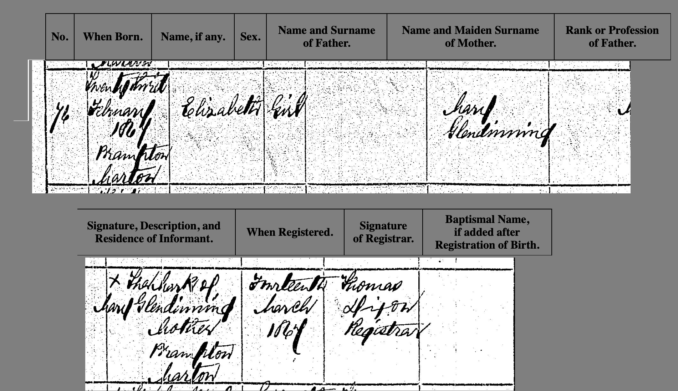

In the late 1850s, the collodion process was invented meaning although camera ownership was still limited to wealthy families, a spreading network of photographic studios gave almost everyone access to a photographer. Looking through the records, my great-grandmother Elizabeth’s father, Thomas Glendinning, died in 1860, therefore missing out on an opportunity to be immortalised in our family album.

Hold on a minute, and this is something I should have spotted the first time around. Mesmerised by iron ore mines, Wazirs and the Duke of Northumberland, I neglected to note my great-grandmother, Elizabeth was born in late February 1867 – seven years after her father died. Oh. As we shall see, mention of February is as significant as that of 1867. We can be sure of Thomas’s demise both from the usual records and via an entry in the deaths column of the 13th October 1860 edition of The Westmorland Gazette,

On the 3rd inst [ie 3rd of the month], at Brampton, Appleby, Mr Thomas Glendinning, aged 54 years.

Probate records show some money was left, a sum not exceeding £300. However, there were family responsibilities. Judging by the 1841 and 1851 censuses, Thomas had farmed with his brother John, ten years his elder, and then retired to be a husbandman – in the league table of such things one whose status lies between a farm labourer and farmer. He had married late, in 1851 or 1852, when he would have been in his 45th year.

Wife Mary was 20 years his junior. They had four children in quick succession with two years between each: Mary Jane, born in 1852, then George, Hannah and finally Thomas who was to die aged six in 1864. The children’s half-sister, Elizabeth, my direct ancestor, was born in February 1867. The census of 1861 shows a widowed Mary occupied as a lowly farm labourer. The children are scattered about; seven-year-old George lives with the Gill family of Staffield. The householder, 59-year-old Mr John Gill, is a farmer of 440 acres. George’s sisters are already in domestic service.

White Mines and Murton Pike,

Karl and Ali – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Regarding that 440-acre farm. The river Eden, besides having created fertile pasture around its banks, has also cut a valley between the Pennines and Cumbrian mountains exposing nature’s gifts to the surface. In my great grandparents’ day, lead and silver were mined. More recently, the spoil has been re-mined for rare heavy metals used in the nuclear industry. Gypsum lies there. Sandstone and limestone are quarried.

High Cup Nick, the firing ranges at Warcop, Dutton Fell and the Pennine Way will have drawn Puffins to the vicinity. They will have noticed the size of the houses, mansions with 18th and 19th-century dates chiselled into the door lintels. At the time of the Gendinnings, this was a very prosperous part of the world – for some.

Leaving the Pennine Way to take in the River Eden at Appleby, walkers pass the road end for my great-grandmother’s home village of Brampton. You will most likely have heard of the Appleby Horse Fair, billed as the biggest traditional Gypsy Fair in Europe. The fair is held on a hillside between Appleby and Brampton. The horses are run along a road at the bottom of the hill and are washed and watered in the Eden. The fair is also known as the Appleby Hill Fair and locals of a certain age may even refer to it as the Brampton Hill Fair. It is held in the first week of June. Can you see where this is going?

Puffins with suspicious minds are already counting on their fingers to the following February when my ancestor Elizabeth was born. I will put you out of your misery. The gypsy fair centres around a ‘selling day’. In 1866 it was held on the 1st June, 36 weeks and 1 day before baby Elizabeth was born. Mrs AWS, the mother to a traveller’s sized brood of children informs me this is an ordinary gestation period. She also summarises my approaching genetic development as ‘all the fun of the fair.’

For once the government made themselves useful and having parted with £2.50, I could download Elizabeth’s birth certificate from the General Register Office website. An unsurprising blank appears where her father’s name should be.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Signatory Thomas the registrar will not have been overly surprised. A contemporary Times article reported the most recent births, deaths and marriage returns, those of 1865, showed that 4.4% of London’s children were born illegitimate. The average for England was 6.2%. In the metropolitan counties and in many of the large towns, the proportion of illegitimate births was below average. However, in the rural areas, the situation is reversed, with North Wales showing 8.3% illegitimacy, Nottinghamshire 9% and Shropshire 9.3%. Two of the kingdom’s highest percentages were Westmorland at 9.6% and neighbouring Cumberland at 11.7%.

Illegitimate meant out of wedlock rather than out of any kind of a relationship, meaning that the percentage, as in Elizabeth’s case, with no father’s name on the certificate, would be lower.

Thinking of that blank space, one’s mind’s eye pictured a local farmer (a gentleman so landed he felt pity for poor Mr Gill with a lowly 440 acres) befriending a lonely widow over a quantity of ale. Hold on a minute, he wouldn’t be a German. Plus at the 1866 fair, the Westmorland Gazette reported that rinderpest and fine growing weather kept the local farmer away. In that year, what was usually a broader agricultural show and market had been no more than the gypsy horse fair we see today.

The Westmorland Gazette had a reporter on the scene. Prices were good. There were healthy sales of agricultural pulling horses, carriage horses, roadsters and ponies. So much for the beasts, what about the visitors, whom the Gazette correspondent referred to as ‘potters’?

“The encampment extended all round the fairground and cooking and washing were going on with as much ease and apparent comfort as if the occupants of the camp had been enjoying the greatest privacy. Although these people do not profess the “respectable dodge” of the Norwood tribes, there is not much to distinguish between them beyond this, that the campers earn their livelihood by the shrewdness of the men in picking up good bargains, and not by wily, fortune telling propensities of their women.

With regard to the extension of the breed, there is little fear of the campers dying out for some time, if one might judge from the infantile screechings that emanated from the camp about the time the potatoes were boiled for the dyke-side dinner.”

Hmm.

The Norwood gypsies were gypsy people living in the Norwood Forest north of London – in those days an expanse of woods and open wasteground populated with well-established gypsy camps. What, you didn’t realise there are different types of gypsy? Read on.

If my ancestor can’t be a local landowner, there are other straws to clutch. Perhaps a travelling German aristocrat buying and selling thoroughbreds? Or an itinerant saddle maker or other skilled artisan displaced from Bismarck’s troubled unifying German states? At least there were no actual, real, live German gypsies in the North of England in Victorian times. Actually, there were and thanks to the efforts of M. Niépce, Mr Fox Talbot and the colloid method, we can take a look at them. Meet the family:

A group of German travelling gypsies at their camp,

Alfred McCann – Out of copyright

This might explain some characteristics of your humble author’s personality – assuming aspects of personality can be passed down through the genes. His aforementioned swarm of kids. The big (gypsy) Mercedes Benz’s. The card school, where those familiar with his technique keep an eye on the bottom of the pack. The wanderlust.

Previously I have recounted my former life more interesting as if an English travelling gentleman concerned with the neglected corners of Her Majesty’s Empire. Then again, perhaps I was just a gyppo on the wander. Regular readers will be aware I can barely write or at least spell. In another part of the gypsy similarity algorithm, friends tell me there’s nothing wrong with my counting.

But I don’t look like a gypsy. I have pale skin and blue eyes. When I was small, I had that bright blonde hair. Likewise, my daughter and one of my sons. This begs the question, what are the origins of the German gypsies? These days there is a name for them, ‘Sinti’. Presumably because of the recent obsession with identity labels and attendant victimhood, the word abruptly appears on the Google word frequency graph in the 1980s.

Some say the word means natives of Sindh in Southern Pakistan as per the origins of other European gypsy people who left that place perhaps a thousand years ago. Others more convincingly argue it is a more recent European loan word derived from ‘Reisende’, German for traveller. Today found mostly in Germany but also in France, Italy and central Europe (and as it turns out, in my house) the Sinti number 200,000 people descended from those who arrived in Germany in about 1540. After all of these centuries, how German have they become?

Before the war, German gypsies were assessed by the civil authorities. Five percent were recorded as ‘full blood gypsies’ but the other ninety-five percent were labelled as ‘mixed-blood’. As recently as 2013, Dublin police removed a blonde-haired blue-eyed infant from a Roma couple on suspicion they were not the parents. A subsequent DNA test showed that she was their child.

As for Elizabeth, she found stability in early adulthood. In domestic service close to John and Ann’s farm, she married their youngest son, my great-grandfather Elihu, in 1888. Fifty years later the local newspaper ran the story of their golden wedding. My grandfather’s commemorative walking stick, engraved with their initials and dates, sits beside me as I type.

It is a long story, told elsewhere on these pages via my grandmother’s nostalgic photo album, but of my generation I am Elizabeth’s and Elihu’s only descendant. Undisputed King of the Worth-Sayings, does this make me the King of the Gypsies too? Apparently there’s a soppy southerner down there in Morecambe who claims to be much the same. Should I challenge him to a rumble?

© Always Worth Saying 2023