© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

I’m in my room, above my ‘Anglo Philippine’ office, in the Durian building in Davao City, in the wild south of the Philippine Islands. It is siesta time and I’ve been interrupted again, despite barricading myself into my room. A security guard and the duty manager are standing beside my bed and have just told me something that they think is very important.

***

‘Thank goodness,’ I reply, ‘I’ve been looking for her. Did Miss Cortez suggest a meeting? By the way, Miss Cortez is not my wife. She’s my contact here as well as a treasured and dear friend.’

They contradicted me, talking over each other excitedly,

‘Not a Cortez, sir.’

‘Your wife, mister.’

‘She called from May-nila.’

‘A booked call sir, we took it at four pm.’

‘Gisele?’, I replied puzzled, ‘she’s not my wife either, she’s my business associate in Manila and Josephina Island. A dear and purely platonic friend, nobody believes me but it’s true, friends. Now, please calm down’.

‘No, no, no, sir,’ they shouted at once, ‘your wife called from May-nila, she is flying south.’

‘What? Gisele is coming down from Manila?’, I was very surprised and alarmed. Gisele’s family weren’t welcome in the South. They’d been driven out of Mindanao previously and Gisele’s life would be in danger if she came here. I represented her family in this place, for a modest retainer, as did a brother-in-law of hers, whose family were from Tagum about forty miles from Davao City.

‘We’ll have to get some serious Kevlar to the airport,’ I responded, ‘I wonder whose bright idea this was?’

I looked to the security guard, ‘Do you know anyone? Colleagues I can hire to protect her? Mayor Duterte is not a fan of hers, or the Webbs, and neither is my dear friend and respectable businessman, Mr Gangster-Gangster Cortez.’

This was going to be a difficult game of four-dimensional chess, the pieces being armed with machine guns and not taking any notice of the rules.

‘By the way, she’s not my wife either. Gisele is a business associate. A separate room for her, on my mega-mega corporate discount rate, please.’

‘No, no, no, sir,’ they shouted together.

The duty manager pulled rank and administered a sitrep, slowly, in words of one syllable.

‘Your wife has arrive in May-nila. She book a line and call at 4 pm. She will fly down to Davao City as soon as she can.’

Realizing my complete puzzlement, he delivered the punch line.

‘Your English wife. She say she has been trying to call since Hong Kong but the phone lines are not possible.’

It just went quiet, as though the world had ended or even had not yet been created. This transcended time. The neighbouring lumber yard fell silent, as did the air conditioning. The geckos lost their tongues. Tinnitus was cured. If there was a dark curtain at Father Conrad’s Assumption Parish Church, it tore in two. The curtains here were closed but I would say that the sky went black. It was kept out of the newspapers but I also would wager that the dead jumped out of their graves and that the ceiling of President General Ramos’s Malacañang palace office fell in.

It is unlikely, but if John Wayne had been standing on a tropical hillside, gazing over the Gulf of Davao, dressed as a centurion, he would have gone, ‘Awwwwwwwwwww,’ and then ‘Awwwww-ed’ a bit more, possibly for a whole week. I rocked back and forward and began to shake. They found a hot drink for me, packed with sugar. It calmed me down. There was a plan. Somebody else, at the local airport with hired goons, would tell her to go back, while I ran away. But first,

‘How did you get into my room?’

Master key. And the chain?

‘There is a hook, for the fatalities and for those trapped while solitary and un-natural.’

Now you know.

* * *

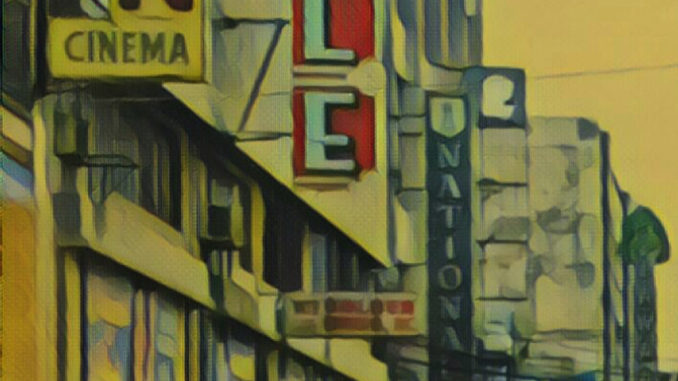

I took a cab, one with a licence plate and a meter with a tamperproof seal hanging from it. You could say what you liked about Mayor Duterte’s power grab, but he had sorted out the taxis and put the fear of God into their drivers. My box of schoolbooks sat on the back seat. The city centre was clogged. Horns honked all around, as vehicles of all shapes and sizes played dodgems towards their destinations.

My driver gave a familiar running commentary. This was the biggest city in the islands, in area at least. Out in Davao Occidental, the city boundary extended well into the plantations. They were proud Filipinos and poor Filipinos but also Davaoeños. That canopy by the sidewalk had seen a grenade attack, another a bomb attack.

‘The insurgents must realise they are only hurting themselves,’ he informed me, ‘the economy would boom, boom, boom even more without the bombings.’

I recognised shallow, stained marks on the pavements and rows of bullet holes along some of the buildings. They were the calling cards of sudden violence, a flash, crack, a slap across the thigh or face, of sticky mist and the roast pork scent of burnt human flesh.

‘You couldn’t come here in the time of Marcos. There were bodies in the street. They shoot them in the gut and leave them for the rats to eat alive through the night.’

We were beyond the city centre now, in an area of tightly packed corrugated homes.

‘This is Agdao mister. Nicaragdao they call it, like Nicaragua in the time of the Contras, except with more violence. Caused by the souls of the aborted bay-bees calling to God for revenge,’ he concluded. He turned to me and smiled, showing a full set of the urban poor’s immaculate teeth, honed by a diet of fresh tropical foods, bereft of sweets ‘n treats.

The Holy Cross of Agdao school described three sides of a quadrangle. The fourth side being a long, high fence with wide double gates, slightly opened, guarded by an armed man in uniform. It was a private school, owned by the Cortez family. Fees were a couple of hundred dollars a year. Discounts might be available. The urban poor gave education a high priority, the money was found from somewhere. The public schools weren’t great. On the other side of the equation, packing the pupils in, and relying on chalk and talk, should return a profit, and monthly, in cash.

Out of the taxi, I was rescued by two older pupils, one carried my schoolbook box. The other led me to the school tuck shop, which was in the style of an improvised roadside hut. I bought every child in sight a drink. They stood in a pack, drinking through straws from small plastic bags of juice.

The Watawat hung from a pole (above an improvised dinner time basketball game), on the parade ground where the children marched and stood to salute it every morning. Marched in the evenings too, if they were members of the Citizens Army Training Corps. We were joined by a nun, bright-eyed and bright smiling. Her habit shone clear white above the dusty ground. I was very welcome. I must follow her. She snapped at a pupil, who picked up my box of books and trailed along behind us.

The demographics of the archipelago displayed itself as we stepped inside the school buildings and walked the length of a corridor. The elementary classes were packed, with not enough desks or chairs for the children, let alone books. As the pupils aged, their numbers thinned. By the final year of seniors, there was space to spare in classrooms that were unaware of the tidal wave advancing towards them every semester.

Walls held explicit photographs and slogans that took me aback.

‘We have earthquake, volcano, poverty. We don’t want AIDs epidemic as well, mister,’ the nun giggled.

The staff room was rather dank, built of dark tropical wood. It was dimly lit, shutters to the quadrangle were closed against the heat and insects. Briefly, I was shown to the Principal’s office. She was an older nun, also shining in white, her English limited to a few words of welcome, thanks and encouragement, through a glowing smile. I sat in the staff room at a long bench table. The teachers, all female, sat peppered around me, all eyes on me.

By way of introducing myself, I opened my box and piled some schoolbooks on the surface in front of me. An ‘ahhhhh’ went around the room. The teachers, some only months older than the older students, gathered around, picking up the roughly printed books and flicking through their coarse pages. A dozen whispered ‘thank yous’ were repeated over and over as if a devotion. A loud gecko seemed to echo the approval from somewhere above the ceiling.

‘Don’t thank me, thank Dane Publishing in Manila, and thank your sponsors and mine, Mr Victorio Cortez, and his daughter, Miss Cortez.’

Did I detect a sudden change of mood? Albeit only a brief pause? Perhaps not. Suddenly they all talked and interrupted each other at once. As a bringer of books, I was an all-knowing oracle, as if an old hag from a distant isle bringing seashells and incense to Delphi.

‘How is Cardinal Sin?’

‘Did you meet the Pope?’

‘Men will not offer themselves to us teachers because of the paper works and long hours. What’s to do?’

‘Will my bay-bee have your blue eyes?’

‘Did you know Mr Cortez’s wife was my teacher when I was a girl?’

A row of old photographs were pinned to the staff room’s cupboards. A hundred pupils became over a thousand in a line of ten black and white pictures. Victorio’s wife was on there somewhere, preparing her pupils for the outside world, but of her husband and daughter, there was still no sign of any kind.

‘I must see Mr Cortez while I’m here, does anyone….’, I was interrupted, a little hand gripped my elbow. The bell must be rung, classes must start. And I must talk to the students. They would want to hear from me. A nun would accompany me.

There didn’t seem to be any equipment, just desks, tables, blackboards, chalk and talk. Nor any glass, windows of insect mesh gave way to the outside world. I had spoken at schools before but not this one, Agdao being previously too dangerous. Presumably Mayor Duterte’s iron grip had extended to this place. If not, I shouldn’t really linger as I might be kidnapped or worse. But the pupils called and I needed to find Mr Cortez, my contact and guarantor, whose absence from all the places you’d expect him to be, was beginning to cause me concern.

The children hoop-ed and clapped as I entered a classroom. Those in the middle, sat on their desks to see better, those at the back stood on theirs. There was a sea of glossy black hair and dark skin ahead of me, topping bright white shirts and various shades of blue shorts and skirts. Diseased genitals glowered at me from posters on the wall. The slogans below them barked an ominous warning (in the children’s dialect) of the wages of sinful pleasure. I found it all rather intimidating. I quietened my audience the way I knew best.

‘Any questions?’

I instructed a girl at the front to ask a question. She sunk her head into folded arms as if she would cry. Pointing towards my best guess of north-northwest, I told the class I come from eight thousand miles that way. It was so cold in my home province, that you can actually see your breath as it leaves your mouth.

‘Ooooooooooo,’ they responded as one.

I pointed due North and told them that I had been in Manila, ‘Six hundred miles that way.’

A hand shot up and a question was asked, ‘Kilo-metres?’ A damn broke, they all shouted out guesses at once, nine thousand, no seven hundred. It’s twelve thousand?

Then, ‘Are you a Prot-est-ant?’

‘Have you ever met a Muslim?’

‘Did you meet the Pope?’

‘In your country when your car breaks down do you throw it away and buy a new one?’

‘What colour are those eyes?’

The girls all laughed. I parried all the questions as best I could and invited more by pointing at raised arms and giving permission to speak by saying, ‘mi-sssss’ or ‘mist-rrrrr,’ in the local pronunciation. I was enjoying myself, something of their enthusiasm was contagious.

‘Jesus was an Asian like us, yes?’

‘How much do you get paid?’

‘Have you been to the Daoist temple where the lady monks shave their heads and the men burn money?’

I made a note of that. I must visit that place. As you know, there was a project in the jungle, my Utopia, that the Daoist monks might want to support. A plaque with an empty space for another donor hung there, no less. The nun called them to order and told the class to thank their guest as he must go now. A sing-song chorus of, ‘Thankyou, thankyou, thankyou,’ filled the room, lifting my spirits further. I raised a hand to silence them.

‘But I must ask you a question,’ I had to show deference, so I turned to the nun, ‘with your permission, Sister. Where can I find Mr Cortez, my esteemed friend and a kind sponsor of this school?’

There was complete silence. Sister pointed towards the door, to usher me away. But I stood firm and scanned the room slowly, trying to look at each and every pupil squarely in the eye, in turn. A boy at the front, too proud to talk in English, perhaps not approving of the fuss being made of this outsider, returned my look and spoke in his own dialect. The class was completely silent. A pin dropping on soft down would have chimed between the wooden partitions. The nun scowled, unspeaking. The oldest girl in the class, standing on her desk at the back, translated, unprompted.

‘He has gone to Bansalan. The home town of his clan, for the ordination there of Brother Ronnie,’ she added, ‘he will not return. The Cortez’s are finished here, by Mayor Duterte, also their associates, Sister says we should not even speak his name.’

There was silence, replaced by more muted whispered thanks. On the way back to my waiting taxi, instead of addressing a goodbye, the nun offered me advice.

‘You will leave this province quick-quick. Do you have a family? Think of them. But if God wills you to go to Bansalan, then there is a phone number for which places are ‘critical’. You must call that number for advice.’

She took a pen and wrote a short number in blue biro across the veins and hairs of my hand, a hand which was twice as broad as hers. Two Sisters of the Poor passed on the other side of the road, in the white and blue lined uniform of the followers of Mother Theresa. They lived in a world where the well-meaning rich could do nothing for the poor except cause trouble. A world where the evils therein could be attributed to the souls of the aborted unborn screaming to God for revenge.

We smiled towards each other. I trusted they’d remember me to God in their prayers that evening. A small child in the gutter played with a dying rat, in much the same way fate might toy with an English travelling gentleman, manipulated into passing closer and closer to his nemesis.

To be continued …….

For a recap of the story so far, please click here.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player