Aleppo station’s main hall,

Enrico Brugnatelli – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Aleppo

‘No, Monsieur. I have only two other passengers – both English. A colonel from India, and a young English lady from Baghdad. Does Monsieur require anything?’ Monsieur demanded a small bottle of Perrier. Five o’clock in the morning is an awkward time to board a train. There was still two hours before dawn. Conscious of an inadequate night’s sleep, and a delicate mission successfully accomplished, M. Poirot curled up in a corner and fell asleep. When he awoke it was half-past nine, and he sallied forth to the restaurant-car in search of hot coffee.

This is a shame because, although later in Christie’s adventure Hercule was able to observe writing on a burnt piece of paper, he will have missed the first four and a half interesting hours of the train trip from Aleppo in Syria to Adana in Eastern Turkey. Perhaps surprisingly, Agatha Christie’s Murder On The Orient Express starts at the northern Syrian city as some of the protagonists board the Taurus Express to Istanbul. Those other two passengers were Miss Debenham and Colonel Arbuthnot whose routes to Aleppo were covered in part one of Eastern Tide Meets Western Shore.

In the restaurant car, Poirot overhears the colonel telling the pretty governess the news from the Punjab. This kiboshes our theory he arrived at Al Maqual in Southern Iraq from Bombay on the SS Gairsoppa. The Punjabi link suggests him having set sail from Karachi in the Sind province of modern-day Pakistan. Having sailed from there, the upside is we can speculate he shared a compartment on the Kyber Mail with our ancestors. Between the wars, my maternal grandfather was stationed in the North West Frontier Territory of Imperial India. My great grandfather, on the other side of the family, in Waziristan. If you try hard enough with your family tree, and are prepared to head sideways as well as backwards, your ancestors will have been there too. My grandfather will have taken the Mail direct from Peshawar. The colonel will have joined him at Lahore after a trying trip, perhaps on elephant back, from the foothills of the Himalayas.

I digress.

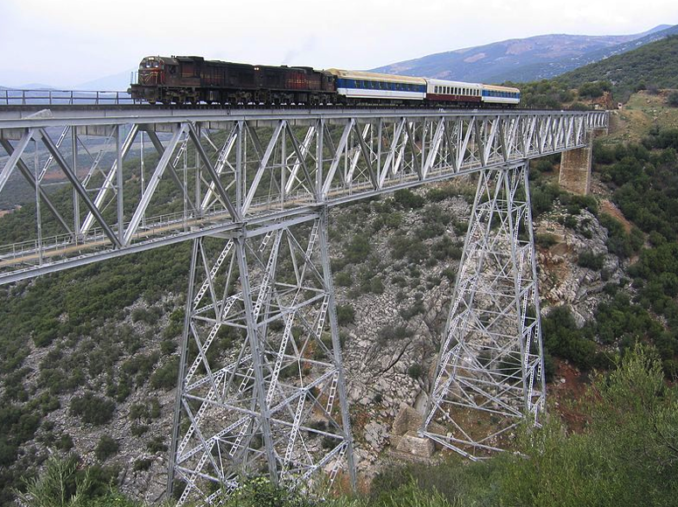

Baghdad Railway, northwest of Aleppo,

Reinhard Dietrich – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Aleppo to the Karasu Valley

Heading north from Aleppo, the land is fertile but nondescript as far as Arfin, east of which the train addresses the Kurd-Dagh, a line of mountains beyond which lies the eastern side of the Karasu river valley. This allows for an outbreak of the kind of interesting railway architecture that always accompanies challenging topography, and that the sleeping Hercule Poirot will have missed.

In my time in Asia Minor and the Levant (the 1980s halfway between Christie’s 1934 murder mystery and the present day), the Taurus Express left Aleppo, or Haleb as it was then known to the railway timetable, after lunch rather than after an early breakfast, at 12:20 pm. Hercule’s four and half hour sleep will have seen the ‘express’ travel 65 miles to the Syria / Turkey border. The complexities of the crossing of which was probably what woke him up. Our other set text for the journey is a useful 1935 description of the route in Railway Wonders of The World which tells of what Poirot missed. Bear in mind that the author was travelling in the opposite direction so we must transpose rises and falls and the order of places.

We rapidly descend and, near Radjoun, cross a deep gorge

As we’re now in the 1930s French-administered former Ottoman Empire, we can add another language to the babel of place-name confusion. Antioch becomes Antioche. Iskenderun is Alexandrette. As for little dots on the map, the suspicion is they never had a spelling to start with and were written down as if an illiterate ancestor’s family name remembered to a parish register by a hard of hearing parson. Fortunately, all spell Afrin A-F-R-I-N except the French who add an un-confusing ‘e’ to the end. Therefore, that northern Syrian city can be used as an anchor point, a Rosetta Stone, when exploring old maps.

A 1928 1:50000 scale publication “Carte des Etats du Levant sous Mandat Francais”, presumably meaning “Map of Levant states under the French mandate,” shows Arfin(e) clearly. If we follow the railway line north from there we come to Radjou, which sounds close enough to Radjoun. On modern-day mapping, it appears as Rajo and in French Wikipedia as Radschu. I won’t trouble the reader with variations of the Arabic. Suffice it to say they’re all the same interesting place where a deep gorge is crossed by,

the Here Dere Viaduct, a steel girder construction consisting of three spans each of 243 ft, one span of 131 ft, and one of 46 ft. The girders rest on towers of steel trestle work 280 ft high.

The Here Dere Viaduct is also known as the Here Here, Herehere, Haradara and Nérê Déré. If you’re listening on the podcast and need to know how to spell Nérê Déré, it contains three acute e’s and a circumflex. The viaduct is findable on satellite mapping not least because of the shadow cast by its near three hundred foot high steel trestlework structure.

Two GE U17C units,

Reinhard Dietrich – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Once across the gorge, we run northwards along the side of the Kurd-Dagh and follow the Karasu Cayi river which defines the border with Turkey. The township, railway halt and border post of Maydan Ikbiz lies at the north-western extremity of Syria. Here, only 27 miles of Turkish territory prevent the Hasidic kingdom from meeting the Mediterranean Sea. Fourteen miles up and across the valley sits the Turkish border post of Islahiye. One hour and three quarters was allowed for crossing between these posts as Syrian and Turkish border formalities demanded.

In my day, the frontier was problematic for British passport holders. Diplomatic relations with Syria were suspended after Hezar Hindawi, travelling on Syrian papers, duped an Irish national into carrying a case containing a bomb onto an El Al jet at Heathrow in April 1986. Suffice it to say, I’ve never travelled on this part of the route and will be joining the train at Adana, along with another Englishman who will be jumping onto the roof while I queue patiently with my luggage. All will be explained.

In the modern-day, via satellite mapping, the railway looks abandoned on the civil war ravaged Syrian side of the border but busies up on the Turkish side. Also visible is a refugee camp at Yesilyurt, another result of the ongoing civil war. From Islahiye the line continues for six miles to Fevzipasa. Still in the valley, a now awake Poirot will have seen a locomotive turntable and eighth moon four road roundhouse beside the station there. Leaving Fevzipasa, the route divides. Two electrified lines head northwards, slowly diverging until our Berlin to Baghdad route swings westward into the Nur (or Amanus) mountains.

Syria,

United States. Central Intelligence Agency. – Public Domain

Through the Nur/Amanus Mountains

As we address those mountains we return to the Railway Wonders of The World description. Remember, ourselves, Poirot, Arbuthnot and the governess are travelling in the opposite direction.

Between the stations of Mamourie and Islahie, a distance of twenty-one miles, nearly six miles of tunnels had to be constructed, the longest of which is the Bagtschi Tunnel, with a length of 5,365 yards. This tunnel was bored through hard rock which was sufficiently compact over the second half to render lining unnecessary. It is located at an average height of 2,500 ft above sea level.

The line rises now again beyond the station of Mamourie and negotiates the Amanus Mountain range by a series of fourteen tunnels. The construction of this part of the line was fraught with considerable difficulties because of the inaccessibility of the mountains.

Radyokid – Public domain

Perhaps surprisingly, what the author doesn’t say is that the fraught construction was carried out in part by slave labour provided by British and Empire prisoners of war captured by the Turks in the Mesopotamia campaign of 1916 – 1917. The Royal Hampshire Regiment website tells of the surrender at Kut-al-Amara, a hundred miles south of Baghdad in April 1917. The British 6th Division, of which the 1/4th Battalion Hampshires were a part, having been starved into surrender after a 5-month siege costing almost 2,000 lives.

The NCO’s and men among the remaining 2,689 British and 10,440 Indian soldiers and camp followers were marched, emaciated, hundreds of miles to the north of Mosul where those still surviving were put to work strung out in camps along the still being constructed railway. In the modern-day, at the end of the Bagtschi tunnel, we meet a new highway that improves upon the old steep and windy D400 road route with a series of impressive tunnels and viaducts. The railway follows it westwards, for Osmaniye, while the eastern part of the superhighway emerges from the mountains about 5 miles north of Fevzipasa where it continues eastwards towards Gaziantep, a gateway city for Eastern and Northern Turkey, Northern Iraq and Eastern Iran.

After Osmaniye the gradients are much kinder. We are now only 50 miles from Adana where we will break our trip. At the halfway mark lies Ceyhan, famous because of the 600 mile long Kirkuk to Ceyhan oil pipeline. Commissioned in 1970, the pipeline takes advantage of the same break in the mountains utilised by the D400 route to deliver up to 1.6 million barrels of oil a day from the Kurdish region of Iraq to the Mediterranean coast. Although the pipeline is named for Ceyhan, it terminates 11 miles to the southeast of the city at the Port of Ceyhan where storage facilities and a series of piers, of up to one and a half miles in length, reach into the Med to fill awaiting tankers. More recently the terminal has also begun to export hydrocarbons from the Caspian – Tbilisi – Ceyhan oil pipeline.

Approaching Adana

Continuing towards Adana, the land is now flat and fertile but interrupted by the crossing of the Ceyhan River. Firmly in the school of deaf parson journalism, Railway World refers to the Ceyhan as the ‘Tihun River’ but accurately describes the railway bridge across it as being, “Composed of four steel girders, each of 164 ft span.” After that, ahead and to the north lies our next challenge – the Taurus mountains – before which we shall interrupt our journey. Also on the right, these days within the outskirts of an ever-expanding Adana, lies Incirlik Air Base.

An aerial view of the airfield at Incirlik Air Base, circa 1987,

MSGT Patrick Nugent – Public domain

As can be seen from the above photograph, Incirlik was impressive but straightforward in the 80s and famous for its 1950’s U2 spy plane runs to Bodo in Norway via the Soviet Union. The railway line follows the perimeter of the southern end of the airfield. Being very flat, your author can’t recall much to see beyond the occasional F-111. Amongst other things, the intervening decades have seen two Gulf Wars, the war against terror, the war against ISIS and the current civil war in Syria. A recent aerial view, shows the facility to be recognisable but much bigger and now surrounded by Adana’s urban sprawl. Since 1980, the city’s population has tripled to 1.7 million. In 1955, the population was 100,000, slightly less than when the Berlin Baghdad railway was begun in the early 1900s. Now well into the city, we cross the Seyham River (or Sheihun in Railway World-ese) on a viaduct described by the publication as,

“A steel girder bridge 1,040 ft long. The bridge is composed of four spans of 177 ft. and one of 315 ft. The masonry piers rest on oak piles.”

After which we are surrounded by train and carriage sheds, including an impressive turntable with quarter-circle roundhouse, which anticipate Adana railway station. Built in 1908, the station was well kept back in my day and has since been magnificently refurbished by the Turks. According to the 1980s timetable, it is now 10 pm. We shall assume this to be one of those late evenings when your author had been called to Istanbul. He stands with his pack and little yellow oblong cardboard Edmondson ticket marked, “Torus Ekpresi, Istanbul, 1st Class”, priced at a very reasonable £2.50 for the 22 hour 777 mile overnight trip to Haydarpasa.

Your hero has calculated exactly where the first-class carriage will stop and has lined himself up with the door. He is wasting his time, the local custom being to pull the windows open from the outside, throw your luggage into the carriage and then climb in after it. Nearby, in the licence allowed to secret agents and filmmakers, after a refreshing motorbike ride along the rooftops of Topkapi’s Grand Bazaar nearly 800 miles away (followed by a gun battle jeep chase), another English travelling gentleman prepares to jump onto the train roof.

A story for next time.

Adana Train Station,

Singring – Public domain CC BY-SA 2.0

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file