Introduction

By inducing a projectile to spin around its own axis its flight is stabilised and accuracy and range are vastly improved. Rifling a barrel by cutting spiral grooves in a variety of forms and rates of twist along its bore has been around since the 1540s but as loading a rifled weapon is slower and more difficult than loading a smoothbore, their use by the military had been limited. Early hunting and target rifles used slightly oversized balls that had to be hammered down the bore with a mallet to engage the rifling and seal the bore but as this was not acceptable in warfare, undersized cloth, leather or paper-patched balls usually incorporated within a paper cartridge containing ball and powder – hence ‘cartridge paper’ – were used that maintained accuracy while making loading much easier and therefore quicker.

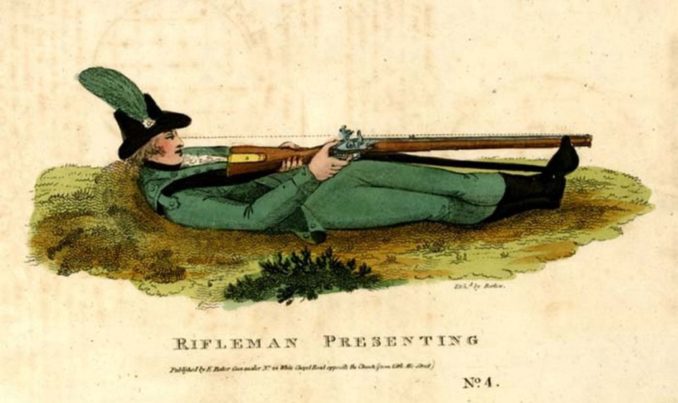

Although flintlock rifles had been in use mainly by hunters and target shooters in the 18th century, it was not until 1800 that the British Army adopted a rifle for use by the specially trained men of the Experimental Corps of Riflemen that in 1802 became known as the 95th Regiment of Foot. Equipped with the famous Baker rifle and dressed in a green uniform with black facings designed to provide some camouflage protection, the Rifles’ role was to act as skirmishers ahead of the main body of troops, sniping at officers and gun crews from concealed positions.

The Baker Rifle 1800-1837

Based closely on the German flintlock Jägerbüchsen (Hunters’ rifles), Ezekiel Baker’s main contribution to the design that was accepted by the Board of Ordnance in 1800 was to reduce the twist of the rifling in the .614 calibre barrel from 1 in 25 inches to an incredibly slow 1 in 120 inches. The advantage of this was that it reduced the amount of fouling left in the barrel thereby making reloading quicker and easier.

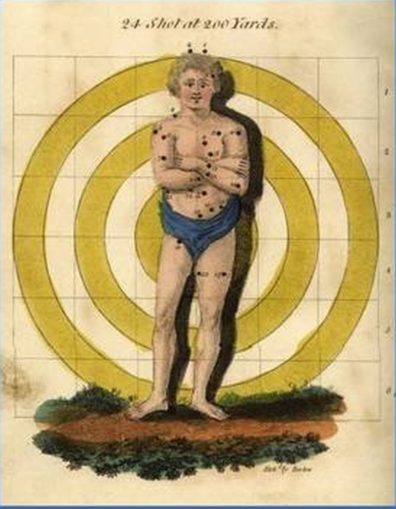

Much has been claimed regarding the accuracy of the new rifle which had fixed sights set at 200 yards but according to Baker himself in 1804:

‘I have found 200 yards the greatest range I could fire at to any certainty. At 300 yards I have fired very well at times when the wind has been calm. At 4 and 500 yards I have frequently fired, and I have sometimes struck the object; though, having aimed as near as possible at the same point, I have found it to vary very much from the object intended; whereas at 200 yards I could have made sure of the point, or thereabouts.’

Nevertheless, when infantrymen armed at the time with smoothbore muskets such as the Brown Bess would be lucky to hit a man-sized target at 50 yards; this was a major leap forward.

After distinguished service in the Peninsular War (1807-1814) and at Waterloo (1815), in common with all other flintlock firearms, the Baker rifle was made obsolete by the invention of the fulminate percussion cap.

After Waterloo, Army funding was cut back drastically together with a feeling that as round balls from smoothbore muskets had served the Duke of Wellington well then they were good enough for his successors and therefore no changes were necessary. This head-in-the-sand attitude led to the rejecting out of hand of a new type of bullet invented by Captain John Norton, a Peninsular War veteran, in 1824 that improved both the accuracy and speed of loading of the standard Baker rifle.

At the moment only specialist gunsmiths produce replica Baker rifles but kits of ‘as cast’ parts can be imported from the USA if you want to build your own. Unfortunately, neither of these options will produce a rifle with the authentic rifling twist rate of 1 in 120 inches; they are much faster. Well-finished rifles sell for £3,000 or thereabouts but a good, genuine Baker with regimental markings (and here buyers have to be very careful indeed), will cost in excess of £10,000 so they are only rarely seen at the range. Shooters have long been begging Pedersoli, the Italian manufacturer of fine quality reproduction firearms, to produce a replica Baker but for some unknown reason and despite the prospect of huge sales worldwide, all requests have so far fallen on deaf ears.

The Brunswick Rifle 1837-1853

The .704 calibre percussion Brunswick rifle that replaced the Baker in 1837 was unusual in that it used a mechanically-fitted bullet so designed that when fired it could not fail to spin. The bullet was cast with a broad belt around its equator that was aligned with two cut-outs at the muzzle to engage the rifling grooves prior to being rammed on top of the powder charge. A combination of distorted bullets and heavy fouling in the grooves made the Brunswick difficult to load and the need to align the belted ball with the rifling only complicated matters, particularly in the dark.

The Brunswick rifle saw very little active service use but tests under range conditions have since shown that it matched the Baker at 200 and 300 yards but was only slightly more accurate at 400. Like the Baker rifle, it was provided with a fixed 200 yard sight but in addition had a flip-up leaf for use at 300 yards.

The Development of the Minié Ball

Had the Committee of Small Arms listened to Captain Norton and tested his new projectile in 1824 they could have had a really effective muzzle loading rifle 30 years before the excellent Pattern 1853 Enfield was introduced. Norton’s experiments had shown that a cylindrical bullet with a rounded nose and a slightly hollowed base that was a sliding fit into the bore would be easier to load than a patched ball and would expand due to the force of the explosion so that its base would grip the rifling and impart spin. Incredibly, the Committee ruled that only spherical balls were suitable for military use and refused even to allow him to demonstrate his breakthrough.

As is the case with so many aspects of firearms development of the period, similar experiments were being carried out in other countries, particularly in France where in 1844 Colonel Thouvenin produced a ‘pillar breech’ rifle that had a projection at the base of the barrel onto which, after the powder had been poured down the barrel, the bullet was hammered in order to expand it into the rifling. Captain Claude-Etienne Minié, the Inspector of Musketry at Vincennes saw that though effective, this was not acceptable to the military and collaborated with Captain Henri-Gustave Delvigne to produce a hollow-based bullet that incorporated a shaped iron plug that would expand its skirt into the rifling when the powder exploded.

The Delvigne-Minié bullet, which is now referred to simply as the Minié or more colloquially the ‘Minny’ ball went through a number of changes to include first a boxwood and then a baked clay expanding plug before it was finally realised that it performed just as well without a plug, provided that only soft, pure lead was used to cast or pressure-form it. One other advantage of the new bullet was that it incorporated bore scrapers and grease grooves that cleaned off fouling, reduced friction and helped keep subsequent fouling soft.

By 1849, Minié’s new rifle was being produced but news of it did not reach Britain until 1850 when it was shown to be vastly superior to the Brunswick rifle. Wellington, who was by then in his 80s, disliked change but even he was convinced that the Liége-produced Minié rifle was the best available and he ordered that 500 .702 calibre examples be produced at the Enfield factory.

These rifles were used in the Crimea in 1854 to good effect. Lieutenant Hanning of the 21st (Royal North British) Fusiliers wrote home in November of that year from Sebastopol:

“I was on a working party the other day at the trenches and I took one of the Minié rifles and went to the front and I picked off three men at about 800 yards in about 30 or 35 shots.”

The range might have been an over-estimation but it showed what the new rifle could do in capable hands.

In America, a .58 calibre version of the Minié ball with a deeper base cavity and a thinner skirt that needed no expander plug was developed by James H Burton of the Harper’s Ferry Armoury in the early 1850s. The Miniés that I use are copies of a dropped Burton ball recovered from a Civil War battlefield cast from a Lyman mould.

It has been estimated that 75 per cent of all the casualties in the American Civil War (around 200,000 killed on the battlefield and half a million injured with hundreds of thousands permanently disabled) were caused by Minié balls. Hits in the body usually resulted in death while hits in the limbs shattered bone for which the only treatment was amputation. No wonder the Minié ball is often referred to as ‘the deadliest bullet of all time.’

The Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket 1853–1871

After the death of Wellington in 1852, attitudes changed with the appointment of General Lord Hardinge, a veteran of the Peninsula, Waterloo and the Sikh Wars, as Master General of Ordnance. Hardinge was firmly committed to obtaining the best possible rifle with which to equip the troops and this resulted in the adoption of the .577 calibre Pattern 1853 (or P53) Enfield that was strong, light, elegant and effective.

The original P53 had a 39 inch barrel with three shallow rifling grooves with a slow twist of 1 in 78 inches. The barrel was attached to the stock by means of three metal bands so this model has come to be known as the ‘3-band Enfield.’

For reasons that I have not been able to fathom, the British used a smooth sided, hollow-based bullet with no grease grooves known as the ‘Metford-Pritchett’ or simply ‘Pritchett’ ball that was supplied in paper cartridges with the bullet nose down to the powder. To load the rifle, the cartridge was torn open with the teeth, the powder was poured down the barrel and then the cartridge was inverted so that the paper-wrapped bullet could be inserted into the muzzle base first. With the bullet in place, the excess paper was torn off and discarded and the bullet was then rammed on top of the powder prior to capping and firing. It was biting off the ends of these cartridges that were allegedly dipped in a mixture of pig fat (unclean to Moslems) and beef fat (sacred to Hindus) that sparked off the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8.

The Pattern 1856 Short Rifle and Variants

In order to provide rifle regiments with a handier weapon better suited to their role as skirmishers, tests were carried out on a rifle identical to the P53 but for a barrel that was six inches shorter and retained by two instead of three barrel bands. This rifle that had the same 1 in 78 inch twist, three groove rifling as the 3-band was introduced in 1856 and naturally became known as the ‘2-band Enfield’.

To compensate for the shorter overall length of the rifle, these original 2-bands were provided with a longer sword bayonet the weight of which was found to impose an unacceptable strain on the barrel.

To overcome this problem, in 1858 the Royal Navy adopted a modified 2-band rifle with brass fittings and a heavier barrel that incorporated five-groove rifling with a much faster twist of 1 in 48 inches. This rifle proved to be more accurate than both the P53 and the P56. In 1860, the Army adopted a similar rifle but with steel fittings known as the P60.

Large numbers of Enfield rifles were supplied to the Confederate forces in the American Civil War of 1861-65 where they proved deadly changing battlefield tactics forever. In the days of the smoothbore musket that was effective to only around 100 yards, determined bodies of attackers might successfully charge across this distance. Gun crews could also set up their pieces at 300 yards from the enemy in comparative safety. Armed with an Enfield rifle, however, a skilled shot was now able to pick off individual targets at 600 yards and beyond necessitating the construction of protective earth breastworks and trenches. The effectiveness of cavalry against infantrymen was also greatly reduced.

The Volunteers

In 1859 fear of another war with France led to the emergence of a mainly middle-class movement of locally funded rifle volunteers, the forerunners of the Territorial Army, who provided their own arms, most of which were military pattern 2-band Enfields in .577 calibre so that they could use standard military ammunition. My .577 Enfield is one of these and was made by Worrall of Chester for a Mr WH Churton who, so far as I have been able to ascertain, rose to be a prominent Chester solicitor and was possibly a founder member of the Cheshire Rifle Volunteers. My assumption is that this rifle must have been made in 1859 as all later Volunteer Enfields that I’ve seen had chequering to the hand and fore end to improve grip in the Volunteers’ keenly contested marksmanship competitions.

The .451 Whitworth Rifle circa 1857

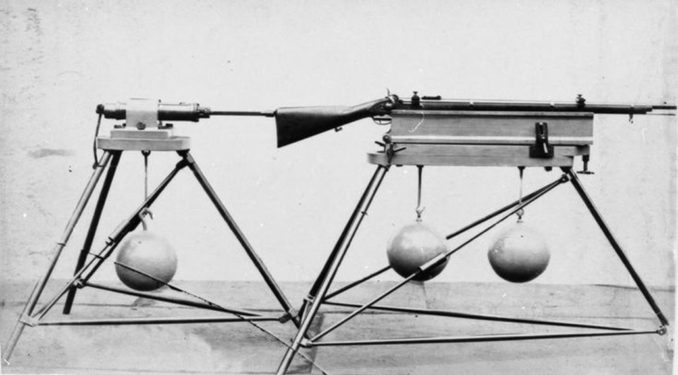

The final 19th century muzzle loading rifle that I must mention is the now legendary .451 calibre Whitworth rifle that set new standards of long range accuracy both on the rifle range and as a sniper’s weapon on the battlefields of America. It was so accurate that when Queen Victoria opened the new Wimbledon ranges in 1860, she pulled the silken lanyard on a Whitworth held in a machine rest hitting the target one inch from the exact centre at a distance of 400 yards. This target can still be seen in the National Rifle Association Museum at Bisley Camp in Surrey.

The Whitworth used a revolutionary system of rifling that had no grooves consisting instead of a hexagonal bore with a 1 in 20 inch rate of twist that was designed to take a mechanically fitted bullet that incorporated a matching twist along its length.

Surprisingly, Sir Joseph Whitworth did not invent ‘Whitworth rifling’; that honour goes to Isambard Kingdom Brunel who had previously commissioned Westley Richards to produce experimental barrels for him based on this principle. Whitworth, who knew and collaborated with Westley Richards, after much calculation and experimentation, determined the ideal combination of calibre, bullet weight, length & hardness and barrel twist rate. Whitworth successfully patented his design apparently without dissent from Brunel or from Westley Richards who went on to mark his own octagonal bore barrels with ‘Whitworth Patent’ although no fees appear ever to have been paid.

The big problem with this amazing rifle was that it fouled rapidly and required a specially shaped ramrod attachment with which to scrape the fouling from the corners of the bore after every couple of shots. This was acceptable on the rifle range but not on the battlefield. While the Whitworth had some success as a sniper rifle in the American Civil War, it proved much too expensive to produce and too difficult in use ever to be adopted as a front line military firearm.

Shooting the Pattern 1856 Enfield Rifle

Compared with any patched ball muzzle loader, loading the Enfield is simplicity itself. After capping-off to clear the nipple of any obstructions, a measured amount of powder is poured down the barrel (paper cartridges containing powder and bullet would have been used in service), a greased Minié ball is then thumbed into the muzzle and pushed down the rifling onto the powder with the loading rod. A couple of light taps with the rod ensure that there is no air gap between powder and bullet which could lead to excessive pressures and a bulged or burst barrel and the rifle is then ready to be capped and fired. In practice, the .575 bullet can be pushed down the barrel with one light stroke and any obstruction from residual fouling that builds up just ahead of the breech is easily overcome.

The standard service charge was 70 grains of fine rifle powder but best accuracy is usually obtained with significantly lower charges in the region of 45-55 grains that are sufficient to expand the bullet skirt into the rifling and maintain bullet stability in flight. Experimentation is necessary to find the ideal combination of make of powder, size of powder granulation, bullet type and diameter, lubricant and cap as no two rifles seem to perform the same – but that’s all part of the challenge and fun of shooting muzzle loaders.

Conclusions

By the 1860s the muzzle loading firearm had reached the pinnacle of its development in rifles such as the British Enfield which fired the deadly Minié ball with great accuracy and devastating effect out to previously unheard of ranges. Excellent as they were, these rifles were not without their problems. Firstly muzzle loaders can only be loaded while standing up and doing this exposes soldiers to enemy fire. Another problem of importance to the military is that of ‘trajectory’ or the path the bullet takes during its flight from rifle to target. At short ranges out to, say, 200 yards for standing infantry and 300 yards for mounted cavalry, bullets sighted at those distances will be dangerous to all enemy combatants. At longer ranges, however, a typical bullet rises in a slow arc way above the battlefield where it presents no danger to the enemy before falling sharply to the ground. A Minié ball from a rifle sighted at 400 yards, for example, rises 11 feet and when sighted at 800 yards its highest point will be a staggering 44 feet above the level of the muzzle. Teaching soldiers to estimate distance accurately was therefore a major concern for musketry instructors.

In order to allow rifles to be loaded and fired while lying down they must be capable of being breech loaded and to make them shoot flatter, the bullet needs to be of a smaller diameter (Whitworth had stipulated .45 to be ideal) so as to achieve higher muzzle velocities.

In the next article we will look in detail at Westley Richards own attempts to overcome these problems and the steep learning curve that I have had to climb in order get one of his fascinating and long obsolete creations to shoot again in as period authentic a manner as possible.

© Tom Pudding 2019

Audio file

Audio Player