Haydarpasa Station Istanbul Aug 2011,

The Stephen J Mason Photography Collection – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong hills. The equator runs across these highlands a hundred miles to the north, and the farm lay at an altitude of over six thousand feet. In the daytime, you felt that you had got high up, near to the sun, but the early mornings and the nights were cold.

So wrote Karen Blixen whose biography Out of Africa, was made famous by the Academy Award-winning 1985 film of the same name with Miss Blixen being played by Meryl Streep. As a kindred soul, who also once gazed upon distant hills when far from home, I dare to echo her sentiment.

I had a room in Adana, at the foot of the Taurus mountains. The Mediterranian coast lay a few miles to the south from where, in the eastward direction, it ran until Iskenderun where Turkey ends and the Levant begins. Those mountains rose to 12,000 feet. The summers were scorching but in winter the passes to the Anatolian Plateau were blocked with snow.

At the start of our tale, we must steal from another author, Agatha Christie, and her Murder on the Orient Express. That story began neither at the famous train’s origin of Istanbul, where the Eastern tide meets the Western shore, nor its destination of Paris or any glamorous intermediate stops such as Belgrade or Trieste.

In Sidney Lumet’s 1974 classic film adaptation, the action begins at Haydarpasa, on the Asian side of the Bosporus, a twenty-minute ferry ride from Istanbul on the opposite, European, bank. Tucked beneath a military hospital and near to Sultan Selim III’s spectacular quadrangular barracks, Albert Finney’s Hercule Poirot overhears a conversation between Lieutenant Colonel Arbuthnot (played by Sean Connery) and Miss Debenham (Vanessa Redgrave). They have just boarded the ferry to Sirkeci Station where the lovers will connect with that evening’s Orient Express and where Poirot miscalculates he will spend some days as a grand touriste at the Tokatlıyan Hotel.

In Kenneth Branagh’s dreadful 2017 remake, so bad the critics assumed it to be a tax dodge, the action starts in Jerusalem. There, in the lazy and unpleasant bien-pensant Anglophobic prejudice of the sneering Islington millionaire media classes, Hercule’s previous case is contrived to present England and her Empire as being responsible for the age-old animosities between Palestinian and Jew.

But Christie’s original text begins on a platform at Aleppo station. It is approaching five o’clock on a cold winter’s Sunday morning in Syria. She introduces the Taurus Express as being a kitchen/dining car and a sleeping car, both in the blue and gold of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits, attached to two local coaches.

Beside them, the detective and a Lieutenant Dubosc sign off some unspecified derring-do in graceful and whispered polished French.

A young woman is already on the train, looking down upon the Belgian and the Frenchman from a sleeping compartment window. It is Mary Debenham who Christie informs us left Baghdad the previous Thursday having, without a proper wink of sleep in-between times, taken the train to Kirkuk and on to Mosel. There, she broke her journey in a guest house before another overnight trip bringing her to Aleppo that morning.

Aleppo Railway station (Gare de Baghdad), Syria,

Reinhard Dietrich – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

In the late 1980s, halfway between then and now (Murder on the Orient Express was first published in 1934), my younger self crouched over his railway timetables and maps on a quiet day in our Adana office. In darkness and with the doors locked, timetables and maps being official secrets after General Evren’s 1980 military coup, I thought of the oddness of the great crime writer’s character’s route.

As every Puffin knows, Mosel is another name for Nineveh, or at least for the part of the modern city east of the Tigris river. Thought to have been the world’s largest city for several decades in biblical times, it was to Nineveh that Jonah was called by God to warn its people of impending disaster. On the way, he was swallowed by a whale.

As further proof that not much changes and time at Bible class is never wasted, seven years ago our parish council were alarmed to receive a handwritten airmail letter, postmarked Mosul, from the Grand Patriarch of Chaldea (or some such). He informed us all was lost. Islamic State was bearing down upon himself and our co-religionists. There was nothing to be done other than to implore fellow Christians to pray. Our prayers were answered with Mosul being liberated from Islamic State in 2017 and Christian worship being subsequently restored.

But Mosel does not lie in a direct line between Baghdad and Aleppo. Are we obliged to take Miss Christie at her word? What would she know of the rail services of Asia Minor and the upper Euphrates valley from her country house in the home counties?

The obvious route for Miss Debenham, avoiding interesting Mosul, would have been by what in today’s money can only be described as the Sunni Triangle terror line from Baghdad to the Syrian border at Abu Kemal, via Fallujah and Ramadi. Ordinary towns in the 1980s, dots on the map in the 1930s, etched to notoriety following the coalition invasion of Saddam’s Iraq in 2003.

At Abu Kemal, Miss Debenham would have been inconvenienced by a gap in the rails necessitating a taxi ride to Dier El Zor. From there, the railway line can be rejoined through another present-day war zone, which includes the likes of Rakka, all the way to Allepo.

As for Kirkup, in my 1980s schedules, the train didn’t go there at all. The line described being direct along the Tigris and Euphrates valley, rather than a curious dog leg to the Turkmen and Kurdish city. All very strange. A mystery worthy of Marple or Hercule.

In answer to our previous question, Agatha Cristie, being an English lady of a certain age, social class and era, knew much more than I. Far from residing in the home counties of country house killings and throttlings on the 4:40 from Paddington, Miss Christie was writing from a room at the Baron Hotel in Aleppo. She knew her stuff.

Chemin de Fer Impérial Ottoman de Baghdad,

Central Data Bank – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Miss Debenham was travelling on the Berlin to Baghdad railway. An iron road born of a Great Game of diplomacy between ourselves the Germans and the Russians. It was Germany that curried favour with the Ottomans Turks and the important course from Europe to the Middle East was begun in 1903 with Teutonic engineering.

A splendid 1935 article in Railway Wonders of the World[1] tells of an Iraqi government line from Basra to Kirkup with a connecting automobile service to Tel Kot Check on the Syrian Border from where the Taurus Express originated. The automobiles being a mixture of Rolls-Royces and Thornycroft busses.

All that was to change across the following decades with the direct line not being completed until 1940[2] and the Sunni Triangle section not being finished until the 1980s[2]. Although both were subsequently closed by wars in Syria and Iraq, the Baghdad West to Ramala section has reopened and enjoys a revival. The attraction being one security check when boarding the train rather than endless roadblocks if travelling by car.

Incidentally, if Puffins are trying to follow all of this in their own atlases, best of luck. Bear in mind each of these places has half a dozen different names, both in Arabic and English, and each of those, in turn, has half a dozen different spellings. Even in my day, Aleppo wasn’t called ‘Aleppo’, rather ‘Halab’. If your humble author may be allowed to frame his excuse through M. Poirot’s own mouth, the great detective might bark in frustration, “I am ‘aving a stab at le spellin’s as best I can!”

In the 1930s, south of Aleppo, carriages connected with Jerusalem, Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor and all points south to Shellal on the banks of the Nile, beyond Aswan. A gap in the rails between Syrian Tropili and Haifa, via Beiruit, was again covered by an automobile service.

Having explained Miss Debenham’s route, what are we to say of her companion, Lieutenant Colonel Arbuthnot? Firstly, in Christie’s text, Arbuthnot is a full colonel travelling home on leave from his post in India and taking in the archaeological sites at Ur of Chaldea en route[3].

From an office in Adana, such a thing seemed preposterous with Arbuthnot, no matter how ‘lean’ and ‘square-jawed’, unlikely to partake in an overland trip across Iran which had nearly defeated Alexander the Great. The British route back to Blighty in those days was via the Suez canal, securing the use of which in the 1888 Treaty of Constantinople had, in part measure, diminished their interest in a railway line through Iraq.

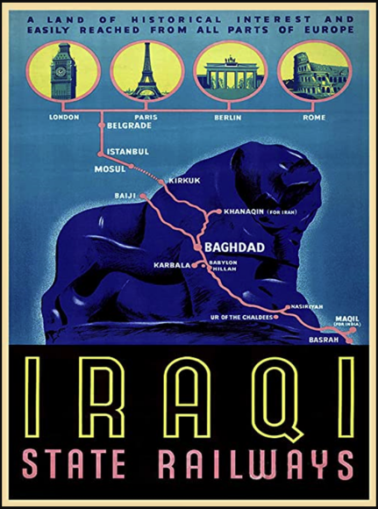

Explanation came from the unexpected discovery of an old railway poster. A lazy glance at the atlas suggests that Basra is at the southern point of Iraq and offers direct access to the northern Gulf. Not so. Basra is inland, with the Shatt al-Arab waterway connecting it to the open sea at Al Faw.

Iraqi State Railways poster, 1930s,

Iraqi State Railways – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

On the poster, a revealing dot on the map northeast of Basra is titled, “Maqil (for India)”. The history books beckoned. The 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica declares a Basran population of only ten thousand, consisting of four thousand Jews, six thousand Christians and no Turks other than Ottoman officials. At the outbreak of the First World War, and with Ottoman Turkey allied to Germany, an invasion of Southern Iraq from British India was necessary to secure continued access to the Persian oil fields.

The battle for Basra took place between the 11th November 1914 and the 22nd November 1914[4] and resulted in the Ottomans being routed and forced upcountry. Thereafter, British forces moved north in what was to become known as the ‘Mesopotamia Campaign’ and which, after series of costly engagements, resulted in the capture of Baghdad on 11th March 1917. The advance continued with a final victory before the Armistice being at Sharqat, one hundred miles north of Baghdad, on the 30th of October 1918. At the end of the war, Iraq was ceded to Britain and administered from India. Similarly, the northern part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire fell under the influence of France, hence Lieutenant Dubosc’s presence in Aleppo in the 1930s.

During the war, the port and rail system around Basra had been much improved. A steady flow of traffic passed by sea from Southern Iraq to Bombay. The Indian Rupee became the Iraqi currency. The British India Steam Navigation Company operated on the route. Their faster ships might make the journey in 5 days at 16 knots. One of the company’s vessels was the Gairsoppa, whose sliver bullion laden Atlantic convoy demise was covered in a highly recommend article by my colleague Reggie’s Mind of Evil. The Gairsoppa was named after a falls in an Indian province neighbouring Bombay. I wonder?

A naval base, HMS Euphrates[5] was established near Basra, at Ashar on the Shatt al-Arab waterway in 1916 but was disestablished in 1919. Re-established at the start of the Second World War it became part of the Royal Navy’s East Indies Station. The outbreak of war was accompanied by an outbreak of mapping. Nineteen-forty maps[6] are available at the British Library and show Basra still a small town. A pleasant mile’s walk (on a cloudy day in mid-winter) leads to Ashar where port facilities and a British Consulate are shown. A mile north of Ashar is a port dockyard and the Rafidain Oil Company refinery, leading to which is a railway line. Better maps are available from 1942, and reveal the whole rail system.[7]

Basra port, during or after WW2,

Sarah – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

At Shu’aiba Junction sits a military base with its own industrial railway. The mainline continues for about two miles to Ma’qil (also known as Margil, Maqil, Al Ma’qil and Al Maqal) whereafter a branch continues to the refinery, Ashar and to a terminus on the outskirts of Basra at a canal that connects the town to the Shatt al-Arab. Another branch forms a loop back to Shu’aiba. On the opposite, sparsely populated, bank of the Shatt al-Arab, a standard gauge Iraqi State Railways line terminates at a dot on the map called Girdalan.

The good thing about being illegally invaded in an unnecessary war is the profusion of high-resolution aerial photographs. Despite decades of tragedy, much has survived albeit now part of a giant concrete sprawl with a population of 1.3 million. Parts of the courses of the old railways can be seen, some covered in roads but with the same giveaway generous curves. Ashar is still there, as is the two-sided jetty of the Rafidain Oil Company. A water treatment plant surveyed in 1940 survives, as does the docksides of Al Maqal, still rail connected and with a passenger station amongst an impressive fan of sidings.

Therefore, we will imagine Colonel Arbuthnot with his luggage in the winter of 1934 disembarked from the Gairsoppa. He has paused at the 250-foot long dockside war memorial[8], which remembers 40,640 of those who gave their lives in the Mesopotamia Campaign, 7,371 of whom were British, 33,256 Indian, eleven Australian, one Canadian and one a New Zealander. Because of the troubled recent history between our two countries, in 1997 the war memorial was moved 20 miles along the road towards Nasiriya. It can be viewed on google maps here.

In my day, five passenger trains a day were timetabled from Basra Ma’qil to Baghdad West, the 336-mile journey taking about 9 hours. Trains were advertised as having first, second and tourist-class accommodations with first and second class seats being convertible into berths for overnight travel. The 22:35 also carried sleeping cars. The first-class single fare was 7.29 Iraqi dinar which in the late 80s was worth about $25 or £15.

If a confusion between the decades resulted in Arbuthnet asking my advice, I would recommend the early train, the 09:45 from Ma’qil, arriving at al Nasiriyar (for Ur of Chaldea) at 12:15. From there, an uncomfortable eight-mile camel ride, thankfully in a straight line, would take the Colonel to the Ur ziggurat. In modern times, it lies within the parameter of Talil Air Force Base. A full day at the ruins would allow Arbuthnot to catch one of three overnight trains from Basra that stopped at Nasiriyar and arrived at Baghdad West between 5 am and 6 am the next morning.

I might also suggest a break of journey at Al Hillah, 65 miles south of Baghdad, for a look around the ruins of Babylon which lie about three miles along the Euphrates river from the railway station.

In the nineteen-thirties, Baghdad had a population of about 300,000, roughly a third of whom were Jewish. Today the city boasts over seven and a half million inhabitants. At Baghdad West, Colonel Arbuthnot rendezvoused with Miss Debenham (a governess returning to England) for the train, automobile and further train journey to Aleppo. Having gathered Christie’s protagonists there, in the next episode they will strike out for Istanbul. West of Adana, I shall join them and add my own first-hand recollections of the Taurus Express to those of the colonel, the governess and Agatha Christie.

To be continued…

The Consulate-General held a small service of remembrance at the Basra Commonwealth War Memorial,

Foreign and Commonwealth Office – Licence CC BY-SA 1.0

References and Further Reading

[1] Railway Wonders of The World, The Taurus Express

[2] Andrew Grantham, Railway Lines in Iraq

[3] Agatha Cristie Fandom, Colonel Arbuthnot

[4] Wiki, The Battle For Basra

[5]Naval History Archive, Basra

[6] Risalpur Survey of India Offices, Basra-shuʿaiba 1:10,000, 1940

[7] India Field Survey Company, Basra Area 1942

[8] Commonwealth War Grave Commission, Basra War Memorial

© Always Worth Saying 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player