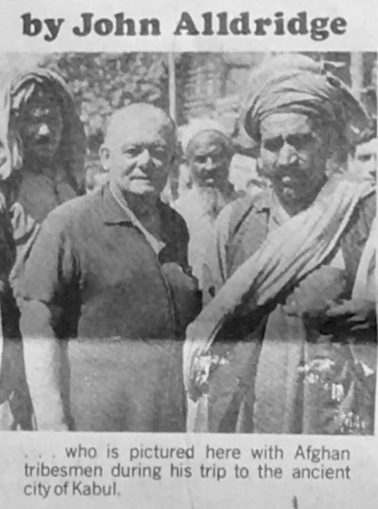

My uncle was, from the end of the war until his death in 1973, Special Correspondent for the Manchester Evening News. I recently came across an article which the paper published in June 1971 in which he described his recent trip to Afghanistan. It provides a fascinating insight into a country which has, to all intents and purposes, disappeared, and hints at what is to come. This is that article, which is reproduced here with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was, from the end of the war until his death in 1973, Special Correspondent for the Manchester Evening News. I recently came across an article which the paper published in June 1971 in which he described his recent trip to Afghanistan. It provides a fascinating insight into a country which has, to all intents and purposes, disappeared, and hints at what is to come. This is that article, which is reproduced here with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

I arrived in Kabul to the sound of gunfire. Somewhere high up there on those crumbling ramparts that climb and twist and turn around the old brown city like the Great Wall of China an elderly British field gun was booming.

It is a sound not uncommon in a country where men still carry rifles and cherish them better than their wives. But these were not shots fired in anger. It was just Kabul’s way of announcing midday.

Kabul is an ancient city that has stood on the crossroads of history for so long it has almost forgotten the names of all the conquerors who have passed through it.

The Famous

Alexander was there once and rested his troops, so they say, in a green valley a day’s march from Kabul – a delightful oasis caught in a fold of the mountains called Istalif, among vineyards and peach trees, where village craftsmen make exquisite blue pottery.

Genghis Khan passed through here in a towering rage in 1222. Tamerlane camped here on his way to conquer Delhi. Babur the Tiger, poet, optimist and supreme soldier, fell in love with it and after he had founded the Moghul Empire was buried here in a place of his own choosing.

For almost a century the British – they suffered their worst military defeat here in 1840 – tried to quench its fiery spirit and when that proved impossible, set it up as a buffer state between Russia and British India.

With the British gone, Afghanistan found herself like a turtle without its shell, ringed by powerful and potentially dangerous enemies – Russia, China, Pakistan.

Spectacular

She did the only thing she could. She threw open her doors to all comers. And so today if you visit one of the country’s spectacular tourist attractions – to the Kabul Gorge, to the blue mosques of Mazare Sarif, to the mountain oasis of Bamyan, or to the Salang Pass, where, at the end of the highest tunnel in the world, you look down from 11,000 feet over the whole white, eye-dazzling spread of the Hindu Kush – you will probably travel in a British car, powered by Russian petrol, over magnificent trunk roads built jointly by Russian and American aid.

Last year 100,000 tourists visited this land of breathtaking mountains, lush valleys, incredibly blue lakes and monuments as old as recorded time. Sixty five thousand of them came by road.

You return to a tourist hotel in Kabul that is either severely Russian or ostentatiously American. Stepping off sidewalks ankle-deep in mud you go shopping down avenues as wide as the Champs Elysees, where donkeys, camels, auto-rickshaws and a few cars jostle for the right of way.

The result is a bewildering mixture of the sixteenth century trying to come to terms with the twentieth.

Outside a brashly modern GPO sit the letter-writers, pen, ink, and paper ready for business. On his way to work a clerk in a sharp business suit made in Bulgaria will check with his fortune-teller to see it it’s a good day to ask the boss for a rise.

Tall Afridi herdsmen stalk down the avenue behind their donkeys. They wear the traditional winged turban and flowing white robes.

But their boots were made in Poland or West Germany.

Wooed

Lost in the maze of the Shor Bazaar – which is pure Hollywood Bagdad – where outraged Afghans once killed a British envoy, you can buy a love-potion, a ring of lapis lazuli, a mess of sticky almond cakes, a fleece-lined Afghan coat, that would cost three times the price in London, or an ancient British Enfield musket, of which there are enough on sale to fit out an army. But you are most likely to be offered a Swiss watch or a radio made in Japan.

Twenty years ago Afghanistan was still a backward state, land-locked in the middle of Asia and barely on the map. Today she finds herself being ruthlessly wooed by her rival benefactors.

Tribesmen in frontier villages, perched like mud-pats on hill-tops, have grown used to the sight of Soviet technicians at work on irrigation schemes in the Jelalabad valley that have made the desert blossom, and Canadian engineers throwing a great dam across the river Warsak.

There are hills on the border ranges where a tribesman, shading his eyes against the blinding sun, can see the vapour trials of the American-built jets of the Pakistanis in the sky to the east and over to the west those of the Soviet-built fighters and bombers of the Royal Afghan Air Force.

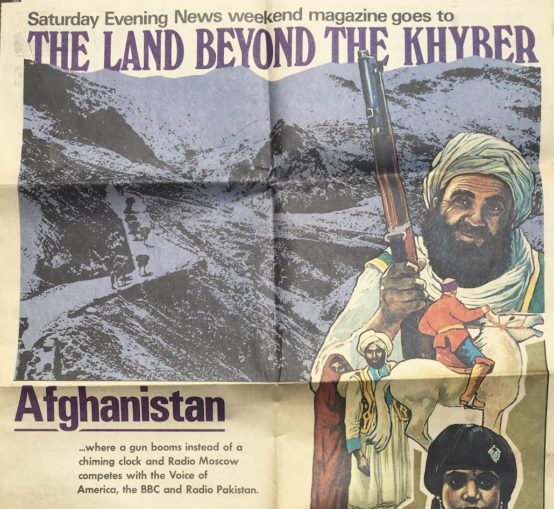

To make sure the Afghans an aware from whom all these blessings flow Radio Moscow broadcasts news in Persian, Pushtu, Urdu and English. The BBC and the Voice of America beam their own versions in several languages; Radio Kabul is on the air daily in Persian, Pushtu, Russian and English; Radio Pakistan in Persian. Urdu, Pushtu, and English.

Without doubt the biggest free gifts – which include that fantastic tunnel two miles long at the top of the Salang Pass – have come from the Russians.

Just how much Moscow has thieved as a result is a subject of endless debate in the coffee-houses. Certainly it is more than the Afghans would like and probably less than the Soviets want. But this year, at least, they have made one significant gain: the over-worked high school students of Kabul, in addition to learning English, French, and German, must now learn Russian, too.

Devout

What the average Afghan feels about the drastic modernisation of his country is also difficult to discover. Afghanistan may now send a contingent to the Olympic Games. But its national sport, which is inherited from its Mongol ancestors, is still a wild rough-and-tumble called Buskashi, which is rather like Rugby League played on horseback, with the carcass of a dead sheep serving as the ball.

These are in the main devoutly, almost fanatically Moslem people, fiercely conservative. When, back in the twenties, King Amanullah tried to drag his country into the twentieth century, turned his palace into a museum, and ordered women to come out from behind the veil, his outraged subjects eventually turned on him and drove him out down the Khyber Pass in his Rolls-Royce.

Today, though many women appear in the streets unveiled, many more go about covered from head to foot in a sort of flowing bell-tent called a chaudri. Though one third of Kabul resembles a suburb of Belgrade the rest of it still belongs in the Arabian Nights.

And the most powerful voice in the land is not Radio Moscow or the Voice of America. Its the voice from the minaret, calling the faithful to prayer.

Featured image: “Afghanistan” by R9 Studios FL (Thanks to all the fans!!!) is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player