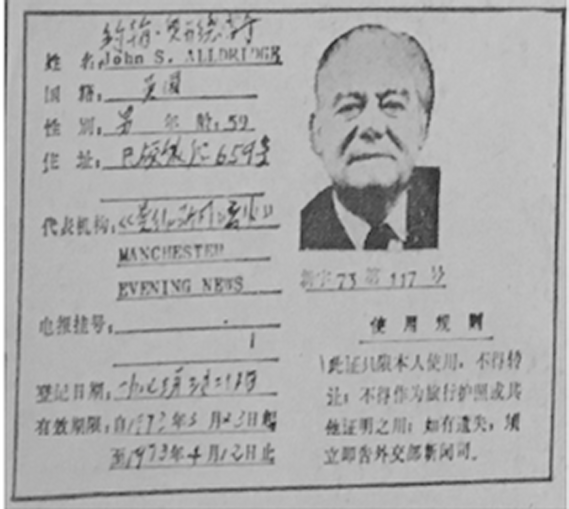

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

Mrs Wu Yuma used to live on a boat on the Wang Po river. Now she lives in retirement with her husband in a single-roomed flat. In the old days she used to go to the pawn shop – now she can use the bank. John Alldridge talks to Mrs Wu in this report from Shanghai, one of China’s most important cities, which has a population of about 10 million.

Mrs Wu banks on Chairman Mao

In Hanchow it was the persistent cooing of hundreds of ring-tailed doves which woke me far too soon. In Shanghai it was the impatient peep-peep of taxi horns. For a moment, between sleeping and waking, I was back in Paris. Which is not so strange really, in a city which was largely laid out like a Parisian arrondissement, even down to the tree-lined boulevard, and the blue-and-white numbers on the houses.

They gave me a room on the fifth floor in what used to be the Cathay Hotel when Victor Sassoon built it back in the early 20s, along with almost everything else on the Shanghai waterfront. Its name has been changed to the Peace. But almost anything else still belongs to the 20s. Even the lamps in the lobby are pure art deco.

From its restaurant on the eighth floor you still get a superb view of the Wang Po river and its shipping. Sassoon’s private suite on the 10th floor still has its oak panelling and priceless collection of jade. But it’s reserved now for executive meetings of the Shanghai revolutionary Committee which runs this teeming city of 10m – a city that makes every mortal thing from turbo generators to ice cream lollies without ever once declaring a budget sheet or an annual report.

My room, stuffed with heavy Edwardian furniture, is enormous. Big enough to accommodate a Chinese family of five with room to spare. I know this from painful observation. From my window, with its heavy Edwardian cream plush curtains, I can see across the street right into the windows of the apartment block opposite. I can see them sleeping two and three to a room the site of a large airing cupboard.

When Sassoon was building the Cathay as a monument to Empire, Mrs Wu Yuma was living with her family in an overcrowded houseboat on the Wang Po river and starting work as a 13-year-old apprentice in a Shanghai textile mill.

Today, at 65, she lives in retirement with her husband, a retired boilermaker, and her young grandson in one room in a three-storey apartment block reserved for retired couples on the Tsao Workers Residential Area.

That room would seem barely big enough to house three. But she had made good use of the space. A teak table is pushed under the window, a huge carved wardrobe along one wall, a brass double bed, three wooden stools, and the household treasures packed in a stack of those heavy cedar trunks bound with brass you see all over the East. And, of course, the large portrait of Big Brother Mao beaming down from one wall.

Cramped

She shares a tiny communal kitchen with two other families but proudly showed me that she has her own tiny gas cooker.

I would have thought it all painfully cramped, particularly with a 12-year-old boy sharing the same bed as his grandparents. But Mrs Wu seems quite contented. Since both she and her husband retired on a 70 per cent pension, they have a joint income of 120 yuan (about £23) coming in regularly every month. Out of that she spends only three yuan, 44 cents (less than 75p), a month in rent and electricity, and roughly 70 yuan a month on food (in China, all food prices are rigorously controlled) for a family of three. What’s left goes into a savings account. “We used to go to the pawn shop. Now we go to the bank”, grins Mrs Wu, the smile on her stolid work-worn face as big as Chairman Mao’s.

No. There is no heating. But then it never freezes here. No bath, either. But it’s only 50 yards to the communal baths. Why is the grandson living with her? Because his mother and father are working in a factory 2,000 miles out west. They were sent there, with thousands of other Shanghai “overspill” in 1956. Oh, yes. They see their boy regularly. About once a year. For a month.

Is she lonely? She chuckled at the thought. She has lived here since the flats were built in 1952. There are 300 other retired people of her own age living here. She knows them all. It’s like living in a little village. And how does she fill in the time?

Well, they have a fine Cultural Hall where they can take part in stimulating political discussions. There’s an old people’s club that gets up sing-songs and chess matches, although she would rather watch than play. But best of all, she likes sitting here by her open window. I don’t blame her. Down below in the dusty courtyard it was spring again. And the first peach blossom was in bloom.

Mrs Wu has a niece, Chew Fan, who had come visiting. A pretty, doe-eyed girl with neat pigtails and delicate hands. She told me she was 17 and already working as an apprentice in a printing and dyeing works. She had gone into the works straight from middle school. Had she asked to work there? No, she had been directed. Was she happy at her work? She looked surprised. Of course she was happy. Her work was important to Socialist reconstruction. What did she like to do when she wasn’t working? She liked very much to dance. Wouldn’t she like to be a professional ballet dancer? She was amused and slightly shocked. Dancing was a leisure-time activity. Work came first.

Better

Had she a boy friend? Chinese women did not think of marriage until they were over 25. What was her life ambition then? To do her own work better.

The Workers’ Residential Area – which is restricted to workers in the nearby mills and factories – is not the newest in Shanghai. It was built in 1952 on land reclaimed from river swamp. Now it houses a population of 69,000, or about 15,000 households, who need never leave the estate once they have come home from work. It has its own supermarket, shops, hospitals, theatre, schools, bath-house, public park, swimming pool, even its own bank. It is run, like everything else I’ve seen in China, by a Workers’ Revolutionary Committee elected by the residents.

I might have known!

I went to one of the nurseries and then to one of the junior schools. I found it an unnerving experience. In the nursery school dozens of roly-poly babies clamoured round me, called me Uncle and then led me off, hand in hand, to see a display of singing and dancing.

For four-year-olds the performance was surprisingly professional, even down to the make-up. Too professional, it seemed to me. They sang about riding a white horse to Pekin to see Chairman Mao, and of course, there was Chairman Mao himself up there on the wall beaming down at them. They played a game which might easily have been Ring-a-Roses. But was, in fact, a dance in praise of the People’s Commune of the countryside.

In a junior class, I suppose of 10-year-olds, this professionalism was even more acute. In a classroom decorated with large wall-posters of infant engine drivers, infant factory workers and infant soldiers all happy at their work, we watched a chorus of little girls in national costume, dancing beautifully. The subject of this dance, we were told, was the women of Korea welcoming the soldiers of Chairman Mao’s Liberation Army. I might have known…..

Before I left Shanghai I visited the mill where Mrs Wu used to work. Shanghai No 3 spinning mill is an old mill, built in the early 20s. It employs a labour force of 7,500, 63 per cent women, who work 1,000 looms.

Most of the original equipment – British, Japanese, and American – is as old as the building. But what surprised me – and, more important, surprised the President of the British Textile Federation who was with me – was how these ingenious Chinese, working from scratch, had stripped down antiquated machinery, rebuilt it and improved it until it was as good as new. Better than new, in fact.

In the weaving shed I recognised a doffing machine installed by Platt of Oldham in 1929 which was now completely automatic. A baling machine installed by a Salford firm long since defunct had only its original name plate left.

“Chairman Mao tells us we must make use of the old while preparing for the new,” the Comrade Director said. Rather smugly, I thought.

To speed-up cone-winding they had invented an ingenious little gadget – like a chair on rails – that slid the operator up and down the machine —which was as good as anything we have in Britain, the President of the Textile Federation assured me.

And with this do-it-yourself equipment they are keeping up a steady average of 5.8 metres, or 6.4 yards, an hour. Most of the work is done by women who worked one of three eight-hour shifts including the night shift. I noticed the old airless weaving shed now had air conditioning. “Our great leader is most concerned for working women’s health,” said the Comrade Director, herself a woman in her 40s.

And although there was no music-while-you-work piped into earphones, you could see these women’s lips moving; chatting away, unconcerned by the roar of the looms, just as they do – or did – in Ashton and Rochdale and Blackburn.

Outside in the mill yard, a fine drizzle was falling. The afternoon shift had just come off and was bicycling home. But for the slogan on the walls and the patriotic posters and the paper flags stuck on the looms, it might have been Oldham.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player