Galta was about to pour her first glass of wine of the day -it was one o’clock and, these days, her lunch tended to come in liquid form- when she noticed a young man peering nervously into her sculptor’s studio which was glazed on two sides. Galta hid the bottle and glass in the wardrobe and, though she was not in the least superstitious, touched its wood for good measure. Her order book was fuller than it had ever been with commissions from various pressure groups who, unfortunately for Galta’s purse, took their time to pay, if they paid at all.

At long last, Galta, who had been pricking her hears, heard a faint knock on the zinc door. As was their wont, her three dogs started barking. She told them to be quiet -rather rudely, I must add- and got off the bed to open. An extremely tall younger man -Galta would never see thirty again- with thick glasses, blond hair and simple but clean clothes stood on the threshold.

“Good afternoon, Miss,” he greeted her shyly. “My name is Rodion. I would like to have a small sculpture made as a present for my wife. Our first anniversary is in two months’ time. I hope I haven’t left it too late?”

“He looks barely 23, and is already married!” thought Galta. “Typical! Probably beats her black and blue when the mood takes him.”

“Do come in, please,” she said in her best public school girl accent. “We’re quite informal here,” she added. “Do sit on the bed, I’ll take the floor.”

Galta’s dogs sniffed Rodion’s trousers bottoms. Oscar the bulldog gave a yelp of approval, then returned to his food bowl. Alyssa the mongrel dropped her red rubber ball and settled in Rodion’s lap. Basil the corgi nestled alongside his leg.

“We have a dog, too,” said Rodion, smiling and petting Alyssa’s head tenderly. “His name’s Cesariot; we got him as a wedding present. The day after tomorrow’s his birthday; his first as a matter of fact, so we’re giving a party at my father-in law’s pub.”

“He likes dogs,” thought Galta. “At least that yob has one redeeming feature. Still, he’s married to a publican’s daughter. How revolting!”

“How can I help you, Rodion?” she asked aloud.

Rodion shifted uncomfortably on the bed, a thin, lumpy mattress resting on two supermarket pallets.

“Sonya, that’s my wife, loves Noah’s Ark,” he said, “so I thought a small sculpted Ark with all the animals would be the perfect anniversary gift for her.”

“A christian!” thought Galta. “I should have guessed. Fascists, every last one of them.”

“We live in a tiny flat,” Rodion continued. “We love it, but we don’t have much space, so the sculpture would have to be quite small. I brought some pictures to give you an idea of what I have in mind. We’re not on the Internet, can’t afford a computer yet; so I got them off Mrs. Cohen at the library.”

“Cohen?” thought Galta, taking the pictures off Rodion. “How many innocent Palestinians has she genocided?”

Galta could not help liking the pictures however: they were illustrations from Victorian children’s books depicting toddlers playing with a wooden Ark and animals.

“Stone or marble wouldn’t be the right materials for this kind of work,” she told Rodion. “If you want colours like those on the pictures, I suggest painted clay, which would have the added advantage of being light. I don’t think a work of such intricacy ought to be heavy.”

“I know nothing about sculpture,” said Rodion apologetically. “I trust you to decide what’s best. I have to go meet Sonya at the station. We live in Exeter. We just came up to London to attend our friend Jason’s special lecture on the Book of Daniel. I’d better give you my father-in law’s phone number at the pub. Ask for Simon or Roger. They’re both in the know.”

After Rodion had left, Galta poured herself a generous glass of wine and examined the pictures. This patron might be an oik, but he sounded like someone who would pay unlike Kayla who was coming to see her later on about a new project for the feminist group they both belonged to. One never knew when Kayla would show up; she was a notorious bad timekeeper. Punctuality was oppressive, she claimed. Galta hid the Victorian pictures in the wardrobe as a precaution. She had a feeling Kayla would not approve of this new commission.

Kayla finally arrived at five o’clock. As usual, she burst into the studio without knocking. She always said that politeness and social graces were yet another form of oppression imposed by the patriarchy. With her came the stench of sweat and deficient grooming. Despite armpit hair practically down to her hip, she refused to use anti-perspirant, had in fact gone to war against toiletries in general, all forms of oppression in her eyes. She was grossly overweight thanks to her addiction to Bent & Gory ice cream coupled with extreme laziness, with her head shaved on one side and hair dyed navy blue hanging limply on the other. She sported soiled silver rings in her nose and eyebrows. When they had first met years ago, Galta had reflected that Kayla had such a beautiful face she could have been stunning with minimal effort. But as it was not egalitarian Kayla half course gone to war against beauty, her own included, and had made quite a success of it.

She let herself drop on Galta’s bed without asking for permission. Every time Kayla visited, Galta was frightened lest the pallets smash under her weight. The dogs kept well away. Oscar buried his big head into his food bowl. Basil retreated out of sight under the sink. Alyssa slipped through the studio door and went for a stroll along the row of houses. She would only feel safe to come back once the guest had left. Kayla resented dogs and the knew it. They were patriarchal, she always said. Even poor Alyssa, female though she was, exuded toxic masculinity.

“I see you still haven’t got rid of that bottle of perfume,” she harangued Galta. “You’re incorrigible. Sometimes I despair of you.”

Galta was careful not to say that it was in fact a new one she had just bought.

“I like the smell,” she mumbled, blushing.

“When will you understand,” Kayla went on, “that perfume, face cream and all that oppressive rubbish were only invented to keep us in shackles?”

Kayla’s father was a human rights lawyer, her mother an investment banker. She had attended the best public school for girls in England, then Oxford University. Yet, she spoke in a broad Yorkshire accent even though she had grown up in Islington, had never been anywhere near Yorkshire as far as Galta knew and secretly called anyone less educated than herself, “common as muck.” In unguarded moments, her English was cut-glass.

Kayla lit a foul-smelling roll-up cigarette without asking whether it bothered Galta (which it did).

“Jocasta finally threw that oaf of hers out,” she informed Galta. “He was like your three fleabags; all he ever did was lie in bed and fart. Jocasta’s supposed to be intelligent. How can she not know that men are all like that?”

“My dogs don’t have fleas!” protested Galta.

“Whatever,” said Kayla contemptuously. “It’s not about this that I’ve come to see you. The committee decided to petition Parliament to have the Cenotaph removed and a new, inclusive work erected in its place. We all agreed on a motion that the Cenotaph is a disgusting, sexist, racist piece of trash and phallic in nature. It celebrates dead white rapists, so it has to go. That’s where you come in.

“What we want is a giant statue celebrating the liberation of female defecation from the patriarchy.”

“I still haven’t been paid for the one on female urination which took me six months to make,” said Galta icily.

“That one is supposed to replace Nelson’s Column. You’ll get your money as soon as those pigs in Parliament give us the go-ahead to topple that criminal celebration of slavery and put yours in its place. We’ve planned a silent pee-in if they haven’t given in by the end of next month. Hundreds of us will descend on Westminster, squat and empty our bladders. It’ll be absolutely majestic!”

“Count me out,” thought Galta. “I’m not dropping my drawers in public.”

“About the new statue,” Kayla resumed. “Lavinia suggested it should be twelve feet tall and made of brown stone, which is quite fitting when you come to think of it.”

It was not in Lavinia’s nature to suggest. In fact, anything resembling finesse was quite foreign to her. Lavinia Slopes was a writer, though sensible people judged her literary production more akin to vomit than writing. Her first novel had sold nearly a million copies and made her rich and famous, something Galta found quite mysterious since she had never met anyone who had ever read, let alone bought it. Its title was so coarse it cannot possibly be printed on this, the most polite site on the Internet. Let me just hint that it consisted of a verb in the imperative beginning with the letter F, followed by the pronoun “Me.”

Lavinia had adopted the pen name of “Slopes” because she used to (as the French so delicately put it) sell her charms on a steep hill somewhere in provincial England, though it was hard to believe that such a charmless creature had ever had any charm to sell, or even give away. Since retiring from the oldest profession in the world, she had most ungratefully turned against her former customers, vociferously calling for white men to be eradicated from the surface of the Earth and for the abortion of white male foetuses to be made compulsory. After a major terrorist attack, she had written a long love poem to the dead terrorists which had, needless to say, appeared in a left-leaning publication. A conservative blog had recently called Miss Slopes “degenerate of degenerates.”

Galta had heard that Lavinia was now in a meaningful lesbian relationship with a penis-having woman. Miss Slopes was also a heroin addict, thin as a rake, with unwashed blond hair and covered from head to toe in crude tattoos. If there had been such a thing as a museum of venereal disease, Lavinia Slopes would have been its main exhibit.

Galta, who was squeamish about this sort of thing, kept her at arm’s length. In her heart of hearts, she believed that Bedlam was where Lavinia belonged.

After Kayla had left, Galta opened the windows wide to air the studio, sat on her bed with yet another glass of wine in her hand and compulsed her order book. A group called Bad Lives Matter had ordered two life-size statues, one of Chairman Mao in a pink bikini so as to emphasize his gender fluidity, the other a nude Lenin with feathers coming out of his behind as a symbol of triumph over reactionary views. But as yet, they could not make up their mind whether they wanted peacock or ostrich feathers.

Galta was in no hurry to start on those statues. She had worked for Bad Lives Matter before and never been paid. An elderly lady wanted a white marble likeness of her cat who was old and dying of cancer. That one Galta would make. She had gone to the lady’s flat to sketch the cat and, despite his age and illness, found him lovely even though she was more of a dog person. The defecation statue she would not consider until she had been paid for the urination one.

“Good luck with that,” she thought to herself.

That left her with two inexpensive orders, the marble cat and Rodion’ Ark. For a while now, she had been living off her father’s inheritance which she had promised to set aside towards her old age. As always, when she was worried, Galta retreated to the Nineties, the blissful era when she had grown up between her father and grandmother, also an artist, the daughter of a painter and an opera singer. She inserted a CD into her Discman, opened her tangerine Ibook and looked up Noah’s Ark.

Galta had been taught that the Bible consisted of nothing but outright lies written to appea solely to schizophrenics and serial killers. Yet, she found Noah’s story rather poetic. She sensed that it had depth and quite possibly a hidden meaning. She then searched for Noah’s Ark in art and was amazed to discover that it had inspired a plethora of artworks, most of them very good, over 18 centuries if not longer.

Around ten o’clock, Galta collapsed into bed as she had done most nights for the past two years or so. She woke up early with a headache and a terrible taste in her mouth. After a cup of strong coffee, she brushed her teeth vigorously then filled her zinc bathtub. As she was soaping herself, it occurred to her that it was high time she cut down on the wine. She slept poorly, waking up several times during the night, and as a result felt exhausted most of the time. The studio was a mess and she could not remember when she had last eaten a proper meal. Worst of all, she could not afford to drink.

Galta went out to buy clay. It was cold and miserable outside. She completed her purchase quickly then hurried back home. She switched on the heating, sat on her bed with a second cup of coffee and looked around her. The studio was spartan and she liked it that way. What she hated was the untidiness, the dirty pots and pans in the bathtub, the half-eaten food left here and there, the open books on the floor. True, her feminist friends lived in pigsties, but since yesterday an unusual sense of detachment had come over her. She would not drink today. Instead she would tidy up the studio and then make plans.

Galta took the rubbish out shortly before lunchtime. The dogs went out with her but did not return for some time. They had always been free-spirited. They roamed the neighbourhood, sniffing bins and car tyres until they fancied a nap on their owner’s bed. They hated being on the lead, instead they walked next to Galta whom they tended to follow wherever she went. The studio was now reasonably in order. She decided that from now on she would divide her day into two parts: in the morning she would work on the Ark; in the afternoon on the marble cat. The only people who ever called her these days were from her feminist group or Bad Lives Matter. As she wanted no intrusion or interruption from either, she switched her phone off before setting to work.

The cat was easy: Galta had made similar statues before; but the Ark proved an unexpected challenge, not the vessel so much as the tiny pairs of animals. They must be identical but at the same time the female had to be slightly smaller except in the case of the lion and lioness. Still, strange as it may sound, the more Galta the atheist worked, the more she enjoyed what she was doing.

Galta finished the cat first and phoned her customer to tell her it was ready. The old lady was delighted when she heard the news. Her pet had just gone to meet his maker, she said, she was broken-hearted and looked forwards to his marble replacement. Because her patron was elderly, Galta, who hitherto had rarely thought about anyone but herself, offered to deliver the statue, which was of course heavy, to her house.

The old lady unwrapped the sculpture, took a step back then gazed at it ecstatically.

“I thought for a minute that Thomas had come back to life,” she exclaimed. “If it wasn’t for the weight, I might mistake one for the other.”

With much care, she set the marble cat on a round mahogany table in the living room and gazed at it some more.

“I could tell straight away you were talented, Miss Galta,” she said, then after a pause resumed, “I’ve been wondering; my sister-in law would like a portrait of her last dachshund. She used to breed them, you see, and now the last one has gone and she misses him terribly.”

The sister-in law came round the following afternoon, an energetic woman in a tweed trousers suit who said she had ran a café all her life but was now retired. She also confided that she had had cancer but had been fully recovered for two years. She had brought several photographs of her late dog, one of which looked like a professional three-quarter shot taken in a studio. The brown dog stood on his hind legs, his front paws resting on a cloth-covered stool.

“This is a beautiful picture,” said Galta sincerely.

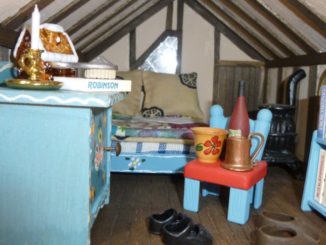

“It’s my favourite of him,” the lady admitted, then paused and looked around the studio. Her eyes came to rest on the Ark sitting on Galta’s tall sculptor’s stool. In the morning, she had started work on a minuscule pair of pigs going up the gangplank. The lady considered the work in progress for a while, gave an almost imperceptible nod of approval and asked wistfully:

“Could you reproduce the photo in marble? We had it taken when my husband was still alive. We had a daughter, you know. But after she got a first at Cambridge, she started finding us common. I hardly ever hear from her now.”

“I think I can,” answered Galta, who for some reason found the picture extraordinarily moving. Less than a fortnight ago, she would have dismissed it as the epitome of kitsch. Since giving up drinking, her sense of perception had changed; she had noticed it herself.

“I have this commission to finish first,” she continued, pointing at the Ark. “It’s for an anniversary. If you’re able to wait I’ll be free to start on your dog’s statue in about ten days’ time.”

Just a week later Galta phoned the number Rodion had given her and asked to speak to Simon or Roger. Roger’s jolly voice boomed on the other end.

“Simon’s in Greece learning Greek. Is it about the statue for Sonya?”

Galta confirmed that it was.

“Simon won’t be back until the day before the party,” said Simon. “If it’s alright with you I’ll come and fetch the statue with Rodion the day after tomorrow. There’s something I need to ask you.”

Despite Roger’s working class accent, Galta felt flattered. It was a long time since, apart from her two elderly patrons, she had been needed by someone remotely normal-sounding.

Since she had been sober, Galta had begun to think more clearly and take better care of herself. Still, she dusted and tidied up the studio then took her clothes to the launderette. Two hours later, as she was about to put the clean linen back in the wardrobe, she caught her own reflection in the mirror door.

“Why do you dye your hair mauve?” she asked. “It makes you look like you’ve just stepped out of the grave. Next thing you know, you’ll vote for Gagajoe. What’s wrong with ash blonde?”

Rodion and Roger arrived at half past ten as promised. Galta’s dogs made a big fuss of them, so it was a while before she could show them the sculpture.

“I haven’t fastened the animals to the Ark,” she told Rodion, “so you’re wife will be able to place them as she sees fit.”

“It’s marvellous!” exclaimed Rodion, truthfully. “Sonya will love it. Look at the camels, Rog. Aren’t they great?”

“They are,” opined Roger. “I’ve just had an idea, Rodion. We’ll ask Savannah to make a wooden stand painted blue to look like water. You’ll keep Sonya waiting outside. Simon and I will put the Ark on the pub’s big dining table, right in the middle with the flowers, drinks and food nicely displayed around it. When the band starts playing, you’ll walk Sonya to the table and leave her there, alone, right in front of the Ark and join the rest of us.”

“That’s a smashing idea, Rog,” said Rodion. “Sonya will go mad for joy.”

“Shall I start packing it for you to take back?” asked Galta nervously.

“In a minute,” said Roger, opening a satchel Galta had not noticed he had brought.

Basil the corgi poked his pointy nose inside.

“I’m afraid there isn’t any food in there, boy,” said Roger, patting Basil on the head, “just books; loads of them.”

“My pub is called the Andrei Sakharov,” he told Galta. “ I suspect you’re too young to know who he was.”

Galta shook her head.

“That’s what I thought,” said Roger. “He was a Russian scientist and dissident who died of house arrest. I wonder if you could make a four feet wide medallion of him in the Socialist Realism style?”

“I’m sure I could,” answered Galta, with more confidence than she actually felt. “What do you want it to be made of?”

“It’s for you to tell me,” said Roger. “Here, I’ve brought you a few photos of the pub. The medallion is meant to go outside on the front wall.”

Galta took the pictures and examined them carefully. The pub was truly beautiful, a huge Tudor house, exquisitely restored.

“Marble wouldn’t look good on a half-timbered wall,” she said. “I suggest bronze, or, at a pinch, cast-iron although it lacks nobility.”

“I think I’d prefer bronze,” said Roger. “Do you know much about Soviet art?”

“Nothing at all,” confessed Galta.

“That’s what I thought,” said Roger. “So I took care to bring you Soviet art books I borrowed from our friend Dasia.”

“I thought Dasia was in Siberia,” interrupted Rodion.

“She’s indeed in a frigid zone at the moment,” joked Roger, “ but she left a key with Gideon.”

“Does she know you went in and took her books?” inquired Rodion, a grin on his face.

“Who do you think I am?” asked Roger, pretending to be offended. “I called her on her mobile first; and let me tell you, I had a hard time getting through. I’ll bet you anything she’s somewhere on the vast steppe.”

“Who are these people?” wondered Galta. “They sound common as muck and yet they own rare art books, order artworks and even pay for them, unlike certain people. And how come they have so many friends, Mrs. Cohen, Savannah, Dasia, Gideon?”

“I’ll make a ten-inch plaster cast first and send it to you,” she told Roger. If you like it, I’ll then sculpt the definitive four-feet mould. Once that’s done I can cast as many bronze medallions as you like.”

“That’s good to know,” said Roger mysteriously. “You’ll come to the unveiling, of course?”

Galta was taken aback by the unexpected invitation.

“Of course, I will,” she said at last.

“Don’t forget to bring your dogs,” said Rodion merrily.

“I never forget about them,” laughed Galta.

After Rodion and Roger had left, much to the dogs’ chagrin, I must add, Galta examined the Soviet art books. She knew no Russian whatsoever, but peering at the back page she managed to make out that they had all been published around the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Yet, they looked much older; the photographs were all black and white for one thing and the glazed pages had an unknown smell, which she presumed came from the ink that had been used. The artworks themselves had an alien style, though not an unpleasant one, and many of them were in fact rather good, full of hidden symbols to evade censorship, Galta assumed.

The phone screeched.

“The silent pee-in is at two o’clock tomorrow,” trumpeted Kayla in that loud Yorkshire accent which now grated on Galta’s nerves.

“I won’t be there,” replied Galta, seething at the interruption.

“What do you mean you won’t be there?” asked Kayla, now sounding like her natural upper middle-class self.

“I don’t urinate in public,” retorted Galta. “I’m housebroken.”

“Then you’ll never get another commission from us ever again, you fascist cow,” spat Kayla.

“What do I care about commissions from people who never pay?” inquired Galta sourly.

“You’re cancelled,” hissed Kayla.

“Good!” said Galta gleefully before hanging up.

What did she care, indeed? She could live for a whole year off the Andrei Sakharov medallion alone. The work intrigued her and Roger had hinted that they were likely to have many more commissions for her in the near future.

Galta gathered her dogs around her and resumed looking at Soviet sculpture.

© text & images Doxie 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file