Lake Pontchartrain causeway, Glenaa – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

If you think Ribblehead (440 yards) and Dent Head (199 yards) are a thrill then you’re going to love the Lake Pontchartrain rail bridge, all 4.4 miles of it. If you prefer to cross your bridges by road then, with the same destination in mind but by a more direct route, twenty-three miles of highway viaduct connects Mandeville, Louisiana with Metairie in New Orleans parish. Everything’s bigger in America. Where the mighty Mississippi meets the Gulf of Mexico, New Orleans, the “Big Easy” isn’t easy to get to – unless you’re a fish. If you do arrive by iron road, perhaps on The Crescent (from New York, 1300 miles in 29 hours), The City of New Orleans (a mere 924 miles from Chicago in only 19 hours) or The Sunset Limited (Los Angeles, 2033 miles, 39 hours, I told you everything was big in America), then you will alight downtown, in the Warehouse District, where Howard Ave meets Loyola, at Union Railroad Station.

New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal. Front, Infrogmation – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

Built in 1954, and replacing a previous Frank Lloyd Wright structure, the new Union terminus amalgamated the services of six other stations onto one site. Designed in a typically blocky and slab-sided fifties utilitarian style, it is very similar to many continental European stations that were hastily re-constructed, about the same time, after being flattened in the War. A very similar example being an Austrian contemporary, Graz Hauptbahnhof, completed in 1956 and where myself (and Mrs Thatcher) would summer in the 1980s.

Halfway between the 1950s and now, before the invention of Trip Advisor and Hotel.com, a little old lady in winged spectacles sat at a Traveller’s Aid desk next to Union Station’s main door, guarding her leaflets while delivering lines such as, “And as an absolute last resort you could always stop at the Y,” alongside, “I know it’s only three blocks but promise me you’ll take a cab. It’s only 75 cents. I’ll give you the 75 cents.”

Back in that particular summer, rather than spilling out onto the Bahnhofgurtel for a distant view of the Grazer Bergland and the promise of some rather expensive nights in the Hotel Frei Raben on Annenstrasse, I found myself in a bleak and strangely deserted Louisiana street, blinded by a harsh Southern sun reflected from concrete and asphalt. The view? The neighbouring Louisiana Superdome. At least the phrase “last resort” suggested that my YMCA accommodations would be cheap and I was saving another 75 cents by walking past the taxis.

Louisiana Superdome, Idawriter – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

The consolidation of rail passenger services allied with a move of freight from rail and barge to road, freed up land near Union Station in the Canal Turning Basin and Warehouse districts. This allowed for the construction of a 70,000 capacity indoor stadium, the Louisiana Superdome. Although New Orleans had wanted a large indoor venue for many years, not least to allow for an NFL franchise, the labyrinthine local politics didn’t allow construction to be completed until 1975.

The Superdome, a modernist structure, a giant B-movie flying saucer, was designed by Curtis and Davis. As well as hosting the New Orleans Saints football team, conventions and pop concerts, it has welcomed seven Super Bowls.

All this talk of lakes, viaducts, canals and bridges should remind us that, by rights, this acreage should be a swamp where North America’s longest river meets the ocean. The fact that it isn’t, is due to a system of levees and sea walls which embank both the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. These were pushed beyond their limits by category five Atlantic hurricane Katrina which hit the city on 29th August 2005.

During the emergency, the Superdome was used as a shelter of last resort for 16,000 people. The situation quickly degenerated. A contemporary Seattle Times article read,

Crack vials littered the restroom. Blood stained the walls next to vending machines smashed by teenagers….. At least two people, including a child, have been raped as the arena darkened at night. At least three people have died, including one man who jumped 50 feet to his death, saying he had nothing left to live for.

Likewise, in a 10th anniversary retrospective, on August 15th 2015, USA Today recalled,

“Inside the Superdome, things were descending further into hell. The air smelled toxic. People had broken up into factions by race, separating into small groups throughout the building that the National Guard struggled to control. A few of these groups wandered the concourse, stealing food and attacking anyone who stood up to them.”

Two decades previous to Katrina, walking the three blocks which separated Union Station and the Superdome from the YMCA on Lee Circle, the situation in New Orleans was also difficult.

In August 1987’s edition of The Atlantic, locally born Nicholas Lemman reported upon the city’s decline. Unemployment was the highest in the United States. Well established local businesses were going broke. The port had over-relied upon a recent oil boom, now turned to a bust. Public schools were poor. A long list seeped in fatalism. The very changes that had allowed the construction of the Superdome had had other consequences. Lemman wrote,

In a sense, the port has been doomed for a very long time, perhaps ever since the advent of railroads reduced the importance of a location at the mouth of the Mississippi River. In recent years New Orleans has been slow to adapt to the age of containerized cargo and was hurt by the shift in American trading patterns to the Pacific, which has made Los Angeles-Long Beach the boom port. The coup de grace was administered, unintentionally, by Congress in 1980, when it passed the Staggers Rail Act, which deregulated railroads. Having never developed a manufacturing base for finishing the goods it imported, New Orleans is a transfer port-most of what’s shipped in is immediately shipped out again.

Added to which, was a crime wave, including,

a group of black teenagers, in a succession of stolen cars, were following people home from parties and holding them up at gunpoint on their own doorsteps. One well-known man was shot in the head. Another lost an eye to a robber’s bullet.

A poll commissioned by The Times-Picayune showed that 71 percent of whites and 78 percent of blacks felt that crime was up from a year before, and fully 55 percent of the whites polled said that a friend had recently been [affected by] activities of crime. Bankers and partners in the big law firms began carrying guns to parties, where, even in daytime, armed security guards had become a fixture.

In December 1989 The Los Angeles Times reported,

Killings in the French Quarter received widespread publicity but drug-related shootings in low-income areas made 1989 New Orleans’ most murderous year on record, the head of the police force said. Two unrelated weekend killings brought the city’s murder total so far this year to 242, two above the 1979 record of 240, Police Supt. Warren Woodfork said. Almost 60% of the slayings were drug-related and about 40% took place in public housing projects.

New Orleans’s 242 murders per year compares with about 600 murders in the whole of Britain.

***

It’s never a good sign when reception is behind an iron cage and registration involves answering questions about your blood group and medical insurance. If the big guy inside the cage with the droopy moustache, shaved head, one earring and tight-fitting flying jacket, is slack-jawed to hear that you walked from the railway station, it is probably because you’ve not only accidentally strolled past what the colonials call a “crack house” but have survived.

As for the area surrounding the YMCA, Lee Circle, I was the only white man, which I quite enjoyed. Fluffy little black girls in fluffy little white dresses queued at the metal detectors, next to the armed security guards, to get into school. Woolworth’s was derelict but open. It still had a sit up and beg cash register where sums of money popped up on metal tabs as the keys were pressed. Customers were often homeless crazies, spending half the day lapping the isles putting stuff into their trolleys and the other half taking it all out again and putting it back on the shelves without buying anything. The surrounding built environment was dirt poor with the occasional enriching expensive European sports car, bought from the proceeds of narcotics.

Payphones had two rows of bullet holes across them. The first, an attempt to steal the quarters. The second, the police spoiling the fun. Local law enforcement, not so much shot first and asked questions later, rather shot first and then kept on pulling the trigger.

However, Lee Circle itself was a very interesting place, with an informative past, challenging present and, as events unfurled, a telling future.

***

In 1803 the United States bought New Orleans from France for thirteen million dollars as part of the Louisiana purchase. At that time the city existed as a French Quarter, bound on three sides by military fortifications and on the other by the Mississippi River. Beyond that were swamps, canals and plantations. On becoming Americanised, the population boomed, not least because of creoles fleeing from Haiti as the French withdrew (under a hail of coconuts and spears) in 1807. As the city expanded, the neighbouring plantation owners developed their land in order to benefit from the property boom.

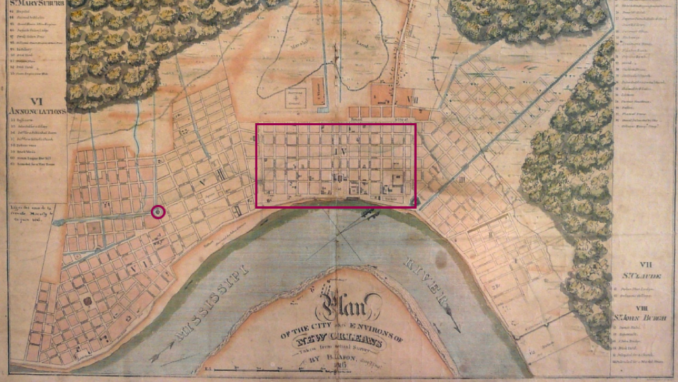

One such plantation was of DeLord-Sarpy who employed engineer Barthélémy Lafon (one of whose maps is reproduced below) to turn their land into a grid-based garden sub-division of tree-lined roads and canals.

1816 map of New Orleans, Barthelemy Lafon – Public Domain

Part of this suburb was the Tivoli Circle, also known as the Tivoli Carousel. It comprised of a circular canal enclosing Tivoli gardens. As it linked the upriver and downriver districts, it became an important meeting point and thoroughfare. By the 1870s the canal had been covered and, it being the South and the decade after the American Civil War, the gardens had been named after Confederate General Robert E Lee. The area was officially named Lee Place within Tivoli Circle but was colloquially known as Lee Circle. It now formed the intersection between avenues that had been named for St Charles and Howard.

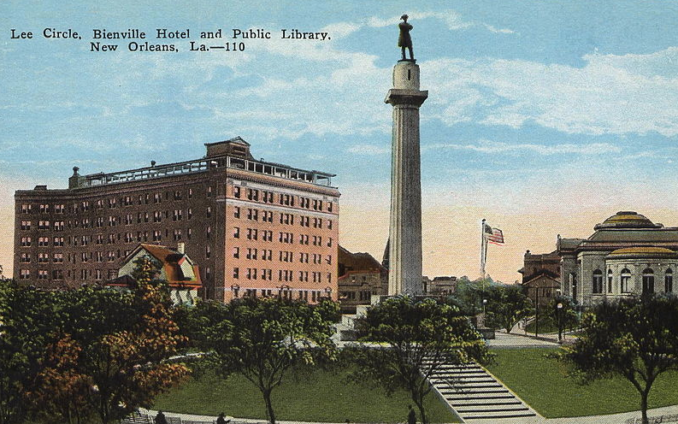

Lee Circle, Bienville, No photographer credited – Public Domain

In 1884, on Washington’s birthday, 22nd February, the Lee monument was dedicated. It consisted of a 16’6” high statue of Robert E Lee, on top of an 8’ foot tall base perched upon a 60’ tall column. Dignitaries such as former Confederate President Jefferson Davies, two of General Lee’s daughters and Confederate General G T Beauregard, looked on.

Lee himself was immortalised facing north towards his enemies, expression resolute, arms folded across his chest in calm strength and defiance. Through the decades, a series of remarkable buildings grew up around him.

We shall explore them, in turn, in a companion article.

Acknowledgements

Old-New-Orleans.com

Richard Campanella, “Lessons learned from the Loss of the DeLord-Sarpy House”, Tulane School of Architecture (2015).

The Times-Picayune / The New Orleans Advocate

Wiki

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player