Abbeytown, Nr Wigton, Cumbria – by Ian Thomson 2019

Mention Cumbria to most people and they generally think “Lake District”. This isn’t always the case, mention Cumbria to a paid up member of the Urban “wokerati” and all you’ll get in response is a blank look or an “Oh, isn’t that somewhere in the North”? But I digress. There’s more to Cumbria than meets the eye, not least it’s rugged coastline, which stretches 120 miles from Levens in the south of the county to the Scottish border town of Bowness-On-Solway in the north. It isn’t that long since I took the railway journey along this coast. I wrote about it here; Postcard From Cumbria (A Week in the Lake District) Part 2

A couple of weeks ago Mrs. C and I decided we’d have a day at the seaside. The weather forecast was pretty good for the time of year and there was a recently installed piece of sculpture that I wanted to have a look at on Silloth seafront. Silloth was established in the mid 19th century, primarily as a deep water port for Carlisle, but it soon found favour with local factory workers and the like who, due to the railway, could get easy access to the seaside. It became a very popular destination for day trippers but its popularity began to wain between the wars. If I had to describe it as a town I’d say it has a faded charm, typical of an English resort of the type that I’m sure many of you have visited over the years.

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2020

Off we went, picnic lunch packed and the dog settled in the back of the car, no doubt eager for a bracing walk along the seafront which has a wide greensward and a three mile long promenade. As usual the Met Office had got its predictions totally wrong. By the time we arrived the weather was closing in, but, being northern and made of hardy stuff we parked up to the rear of the greensward on the main road, got ourselves wrapped up and set off on our adventure. The piece of sculpture I was interested to see is by Ray Lonsdale, a steel fabricator and sculptor from the North East of England. The family of a man called Peter Richardson, who had originally commissioned it, ensured that it was placed on the seafront following Mr Richardson’s death. It’s called “Sunset” but the locals have several names for it, including “One Man and His Dog” and “The Big Fella”. Mr Richardson considered the view out onto the Solway to be the finest view in Britain, there are days when he may be right, but not on the day we were there!

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2020

It was becoming increasingly windy but we soldiered on, past breakwaters and a roiling sea, taking full advantage of the ozone and considering ourselves lucky that at least it wasn’t raining. We’d gone maybe a mile or so past the statue when our luck ran out. It began to rain, not the kind of rain that you can walk in beneath an umbrella and take pleasure from, either. It was the kind of rain that came at you straight off the Irish Sea and almost parallel to the ground, roughly from the direction where the car was parked. By the time we got back we were soaked to the skin and the dog was in a sorry state, but we toweled her off, dried ourselves as best we could and ate our lunch sat in the car with the heater on.

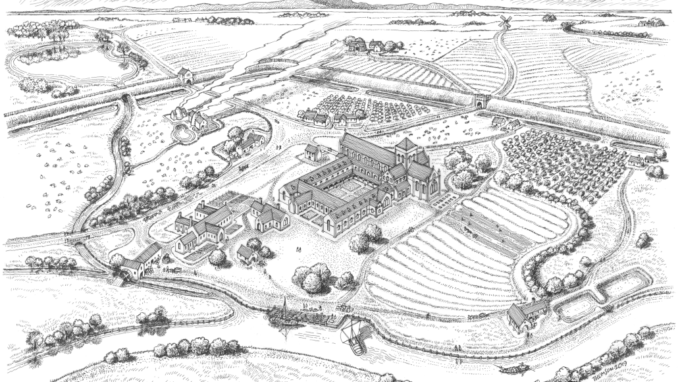

Mrs C is something of an amateur genealogist and she suggested that we stop in Abbeytown on our journey home. It wasn’t out of the way and she had some evidence that one or more of her ancestors might be residing in the churchyard. This very slight detour turned out to be one of those happy instances when you discover something that you had no idea of but turns out to be, at least to me, utterly fascinating. Abbeytown, also known as Holme Abbey, is the location of St. Mary’s Abbey. When the Abbey was established the area surrounding it was called Holme Cultram, a name deriving from the Norse words holmr meaning land surrounded by water, culter meaning cultivated and an Old English word, ham meaning settlement. The history of Holme Cultram Abbey is long and rich. It was founded by Cistercian Monks in 1150 as a daughter house to Melrose Abbey in Scotland and granddaughter house to Rievaux Abbey in Yorkshire. Originally the land was in the holding of David of Scotland but it was reclaimed in 1157 by Henry the 2nd and soon became very prosperous through farming, fruit growing, the trading of salt harvested from the marshes and hunting.

Throughout the Middle Ages Holme Cultram Abbey remained prominent in both political and religious matters and, due to its wealth and its strategic border location, was often the focus of cross border raids by Scots. In 1216 Alexander the 2nd raided, his men even stealing the bed linen of sick monks in the infirmary. By 1235 lay brothers had been granted a charter to bear arms to protect the Abbey, it’s farms and orchards and its associated granges from these frequent raids. During the late 13th and early 14th centuries the Abbey became the base for Edward the 1st during his campaigns against the Scots. The English fleet was based at nearby Skinburness and kept the army supplied with all it needed for its ongoing campaigns. Edward 1st spent his last day at Holme Cultram, signing charters. He died the following day, whilst crossing Burgh Marsh, possibly on his way to Lanercost Priory. The Scottish raids continued well into the 14th century, so much so that a grant was given to excavate stone from a nearby quarry to facilitate ongoing repairs.

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2020

By 1538, when the dissolution of the monasteries was enacted by Henry the 8th, Holme Cultram Abbey was the second wealthiest in Cumbria, after Lanercost. It had widespread trading connections and land holdings throughout England, Scotland and possibly Ireland. Along with many other such places Holme Cultram was demolished and the good building stone was sold off. Many houses in the local area have Abbey stone within their make up. Throughout the 17th and into the 18th century the remaining buildings and towers fell into further disrepair. In 1703 a board of trustees was appointed to halt the decay and carry out refurbishment of the church building and attached cottages. Much of the work to save the church was completed by 1730 and a new floor was laid in 1833. Renovations continued throughout the following years, finally being completed in 1973, when they were officially opened by Princess Margaret.

By Dougsim – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

In 2006 the renovated Abbey church was the target of an arson attack and was gutted by fire which destroyed many of the original records. It took nine years for it to be fully restored for a second time and a further two years to restore the cottages, porch and balcony. I could go on, there is an interesting little museum room attached to the church and the surrounding area has revealed much of the history of the Abbey and it’s environs through the continuing, painstaking and very sterling work carried out by volunteers from the West Cumbria Archeological Society, without whose efforts much of this information may well have remained hidden. It’s all too easy to dismiss how the history of the Borders has had such an impact on the history of Britain as a whole but the more I learn about it the more I am fascinated by it. If you’re ever in this part of the world don’t restrict your visit to “The Lakes”, there’s much to see and lots to learn when you get off the beaten track.

I’m indebted to Jan Walker and her colleagues at the West Cumbria Archaeological Society, who are responsible for producing the booklet “Holme Cultram Abbey; An Archaeological and Historical Guide”. Much of the information in this article is gleaned from this publication. I wouldn’t have been able to impart the above without their hard work. Anyone interested in what they do can contact them via mailto:westcumbriaas@gmail.com or visit their Facebook page, West Cumbria Archaeological Society.

© Colin Cross 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player