In Africa, generally speaking, museums usually are thin on the ground. Underfunded, poorly maintained (if at all), they often present a version of history barely refreshed since colonial times. Rwanda is an exception. Currently it must boast more museums per square mile than any other African nation-state. In Kigali and Kibuye, Gikongoro and Butare, Nyanza, Mulindi, distinctive brown signposts point to venues where the displays are pristine, labelling precise and well-trained and informative staff.

This was no accident. After the genocide, Western embassies (read US on instructions from Madelaine Albright covering her mistakes in Somalia and Rwanda), flew RPF officials to Israel to visit the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Centre. The lesson did not go to waste, a trip to the Kigali Genocide Memorial where 250,000 are interred, has become an obligatory part of any VIP (read Western leaders) visit.

Museums set officially approved narratives in concrete. As counternarratives, complexities and nuances get lost, usually deliberately. Rwanda’s heritage sites were always destined to become a vital tool in the armoury of a regime bent on determining who and what is exactly remembered.

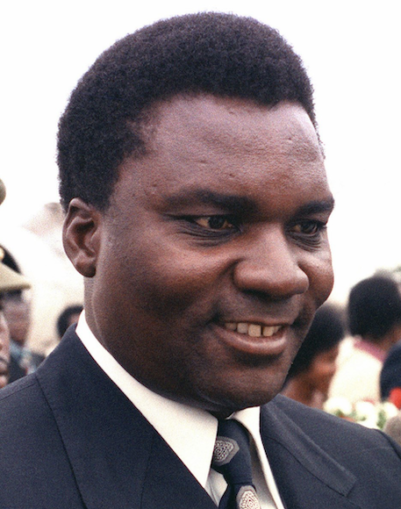

President Juvénal Habyarimana of RWANDA,

Templeton – Public domain

President Juvénal Habyarimana, having already, as army chief of staff, ousted his former boss (another coup), built his presidential villa under the flight path routinely traced by aircraft coming in to land. As a military man, he was relaxed near his army, with Kanombe barracks just up the road.

He clearly saw this as his last redoubt. As it turned out, it was all for nothing. Correctly fearing his life, knowing at some point, his turn would come, he’d only prepared for a ground assault. No “home improvement scheme”, however good, stood a chance against the directness of a SAM, launched as he sat next to his Burundian counterpart Burundi’s Cyprien Ntaryamira (Mobutu was supposed to also be on board but declined at the last minute) in a French crewed Dassault Falcon returning to Kigali from Dar es Salaam on the evening of 6th April 1994.

Hearing the engine of the descending jet, Habyarimana’s family knew the president was about to land. Then a missile snaked through the sky just missing the aircraft. The French pilot tried desperately to take evasive action, a second missile hit home. The Falcon jet exploded into a ball of flame, showering metal debris and body parts onto the presidential villa’s grounds.

The jet’s downing and assassination of two African presidents served as the immediate genocide trigger. Within hours of Habyarimana’s death, Rwanda’s presidential guard had erected roadblocks around Kigali and Akazu youth militias fanned out across Kigali to avenge their slain president and root out the enemy within: not only Tutsis, but Hutu politicians, journalists and any senior officials deemed hostile to the regime.

Up in their HQ in Mulindi, the RPF scrambled. As a full-throttle mil operation got underway, the 600-strong RPF battalion was ordered to move what civilian politicians it could locate to safety.

Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana was among the first high-profile Hutus to die, killed alongside her husband by Bagosora’s presidential guard. Ten Belgian UN peacekeepers who had been guarding her were disarmed and tortured to death, their cries relayed to their commanders on their army radios. It prompted the immediate withdrawal of the UN’s Belgian contingent, its largest.

Genocides don’t take place in a vacuum: there’s always a context and a build-up (previous articles refer). For decades a mirror imaging, ethnic pogroms in Burundi and Rwanda had echoed one another, depositing layers of emotional numbing upon each community. Serving to convince both Hutus and Tutsis the other side was morally beyond the pale, they had effectively established mass killing in the collective mind as the way in which Tutsi-Hutu tensions were resolved.

I wasn’t until human rights groups such as London-based NGO African Rights and Human Rights Watch started issuing statements that many outsiders began to grasp what was happening was not random “ethnic killing” but part of an operation with a deliberate strategy, organisers, and a hierarchy of cooperative agents.

As Habyarimana’s forces, weakened by faction fighting, dissipated their energies slaughtering civilians, the RPF advanced. One force headed east to Gabiro then turning south toward the Tanzania border, aiming to secure provinces where Habyarimana’s forces were weak. The main force struck straight at Rwanda’s core towards Kigali. Despite RPF’s ubiquitous modern-day label as the “former rebel group that stopped the genocide”, the movement’s priority was capturing power, not saving lives.

When 10 days after the presidents’ assassinations, the UN bumped gums about reinforcing its demoralised Kigali peacekeepers, the RPF fiercely objected. Behind the closed doors of the UNHQ US’ UN Rep Madelaine Albright (together with UK’s UN Rep Sir David Hannay) UN cables blocked more prompt action. RPF spokesmen Gerald Gahima and Claude Dusaidi airily claimed “there was no point, the genocide is almost completed, most of the victims of the regime have either been killed or have fled,” which wasn’t true.

The RPF once more objected in June as President Mitterrand finalised plans to dispatch Operation Turquoise to Rwanda, claiming, once again, that since all Tutsis have died there was no one to save.

It took months for member nations to contribute troops to the 2nd UNAMIR II. By the time they started arriving, the RPF had secured its hold on the east and was ratcheting up pressure on Rwandan troops dug in at strategic sites in Kigali, Ruhengeri and Bugesera. By 4th July, the RPF had effectively taken, with one exception, the country.

That exception thanks to Operation Turquoise, a chunk of territory in the southwest remained under French control. Paris would only hand over to UNAMIR II after high-profile members of Habyarimana’s administration had been ushered to safety.

Seth Sendashonga

Ask any former RPF members what first alerted them to the fact that the movement had turned down a sinister path, the majority point to the same event: Seth Sendashonga’s death in a barrage of AK47 fire in Nairobi.

The RPF having created a government of national unity in July 1994, invited Sendashonga, a politically moderate Hutu, to be the minister of the interior. For much of his tenure, Sendashonga had written a barrage of memos to Kagame about killings and forced disappearances that were reported to have been carried out by elements of the RPA. On 19 April 1995, Sendashonga rushed to Kibeho in an attempt to calm the situation after RPA soldiers shot several Hutus in an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp. After returning to Kigali, he briefed PM Faustin Twagiramungu, President Pasteur Bizimungu and Vice President/Defence Minister Paul Kagame seeking assurances the RPA would exercise restraint. Following the massacre of a large number of IDPs at Kibeho on the 22nd, the RPA refused Sendashonga entry to the area.

After his attempt to seek redress for victims of Kibeho was turned down, Sendashonga came to the conclusion that the ‘Ugandan Tutsi’ who controlled the RPF would not tolerate any dissent and were willing to carry out mass murder to achieve their goals. However, both Sendashonga and Twagiramungu, also a Hutu, thought the situation might be salvaged as the political split did not precisely mirror ethnic lines; some Francophone Tutsi politicians in the RPF felt excluded by the English-speaking Tutsis who had come from Uganda.

Sendashonga decided to take a stand against arbitrary arrests after 15 prisoners had suffocated to death after being detained some days after Kibeho, stating, while cautiously referring to detainees as ‘criminals’, “Of late many criminals have been arrested following the closure of Kibeho camp, thus making the prisons full beyond their capacity.” This infuriated Kagame, who some days before had given a speech proclaiming, “Over 95% of the former Kibeho people have returned to their homes and are in good shape.”

The RPF Department of Mil Intel had leaked a memo to the press stating that Sendashonga, Minister of Finance Marc Ruganera and Vice Prime Minister Col. Alexis Kanyarengwe, all Hutus, were under their watch. As killings and disappearances continued without any pause, Sendashonga made the dramatic decision to disband the Local Defense Forces (LDF), which had been set up to replace the police after the genocide but were subsequently linked to a large number of arrests, murders and disappearances. However, the LDF was the tool the RPF used to keep track of rural areas, further aggravating Kagame.

As things reached breaking point, Twagiramungu called a special council of ministers on security matters that began on August 23.

Running for three days, the meeting turned into a conflict between Kagame and Sendashonga, who’d received the backing of Twagiramungu, Ruganera and, somewhat surprisingly, Aloysia Inyumba, the Tutsi minister of women’s affairs.

Two days later, PM Twagiramungu resigned, but was outmanoeuvred by President Bizimungu, who did not want him to leave the government on his own terms. On 28th August, Bizimungu came before parliament and asked for a public vote that succeeded in firing Twagiramungu.

The next day, Sendashonga, Minister of Transport and Communications Immaculée Kayumba, Minister of Justice Alphonse-Marie Nkubito and Minister of Information Jean-Baptiste Nkuriyingoma were fired. Sendashonga and Twagiramungu were placed under house arrest and their documents examined for any incriminating evidence, but were eventually allowed to leave the country unharmed by the end of the year.

Sendashonga went into exile in Nairobi. There, he’d set up an opposition party with his friend Twagiramungu. In February 1996, he’d been approached being offered documents exposing dissent in RPF ranks. Sendashonga had driven with his nephew to meet the informer source. Both were shot but survived a bungled assassination. Sendashonga recognized one of the would-be assassins as his former bodyguard from when he was a minister. The other was Francis Mgabo, a staff member at the local Rwandan embassy, who was subsequently discovered attempting to dispose of the pistol he had used in the attack in a toilet in a petrol station. The Kenya government asked Rwanda to withdraw Mgabo’s diplomatic immunity so he could be arrested and put on trial. Rwanda refused, resulting in a row between the two countries in which Kenya closed the Rwanda embassy and the two countries broke off diplomatic relations.

In July 1996 Sendashonga held a press conference in Chester House Nairobi. Presented reams of leaked official documents containing hundreds of thousands of names of Hutus who’d been slaughtered by the RPF before, during and after the fall of Kigali. Pointing to the tallies, district after district, Sendashonga stated RPF was responsible for at least 500,000 deaths.

Many of the killings happened during the RPA’s advance across Rwanda, when no international human rights observers had been present to witness. Arguing that both RPF and Habyarimana’s expelled forces were compromised by the amount of blood on their hands, called for an international mission posted to Rwanda and the country run under an international mandate, while a new untainted army was recruited.

The notion of a “double genocide” that killings by RPF counterbalanced by the those of Habyarimana’s forces was familiar territory: France’s Quai d’Orsay had been briefing to that effect all along. The English speakers, briefed by US and UK diplomats, in contrast, regarded that as classic disinformation.

Having agreed to testify International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the French Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, and would have been the first current or former member of the RPF to testify for the defence presenting key evidence of RPF’s responsibility for the downing of the presidential plane, on 16th May 1998, at about 5 pm, Sendashonga was being driven home in his wife’s UNEP car when he was shot and killed, along with his driver Jean-Bosco Nkurubukeye, by two gunmen firing AK-47s.

Three men, David Kiwanuka, Charles Muhaji and Christopher Lubanga were arrested by the Kenyan police. Kiwanuka was claimed to be Rwandan, despite his typically Muganda name, while Muhaji and Lubanga were identified as Ugandan.

Despite the problems with the Kenyan criminal case, the three men remained in jail until 31 May 2001, when they were released from jail by a Kenyan court which found that the murder was political and blamed the Rwandan government.

In a December 2000 hearing, Sendashonga’s widow, Cyriaque Nikuze, claimed the Rwandan government was behind the assassination and reaffirmed he had been scheduled to testify before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the French Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry.

Nikuze stated in court, the Rwandan embassy official Alphonse Mbayire, who was the acting ambassador at the time, organized the assassination. Mbayire was recalled by his government in January 2001, immediately after Nikuze’s testimony and shortly before a new hearing was to begin, he was shot dead by unidentified gunmen in a Kigali bar on 7th February 2001.

© AW Kamau 2023