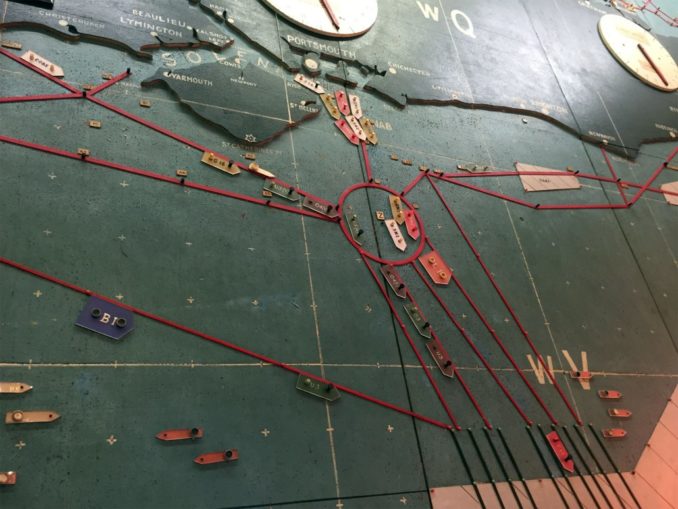

D-Day map, Southwick House.png: Hchc2009derivative work: Hogweard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Why is this effort necessary? 75 years after the greatest combined military intervention the world has ever seen rid humanity of the scourge of National Socialism, we have reached a point in our communal experience where we frequently find ourselves wondering: was it worth it? What would be different in Europe and indeed the wider world today had D-Day never happened? This is not an easy question.

And why was Germany the target ? Well there’s an obvious answer to this question and a not so obvious one. Let’s start with the obvious one. After six years in power, a German coalition government run by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party had – without prior declaration – attacked and invaded Poland. Once this country had been conquered, the Nazis made their peace with Stalin and went on the rampage in the North (Norway) and the West (Low Countries & France). Meanwhile, efforts to “erase” the Jewish people were ramped up to an industrial level in extermination camps such as Auschwitz. During the war years, Germany would regularly prioritise the Holocaust over their war effort. This is what one school of thought today describes as the nutshell of German exceptionalism.

Let us now have a look at the not so obvious answers. To do so, we can briefly – and necessarily in broad brushes – reflect on the historical conditions which made Germany what it is today. So let’s have a look at a bit of history.

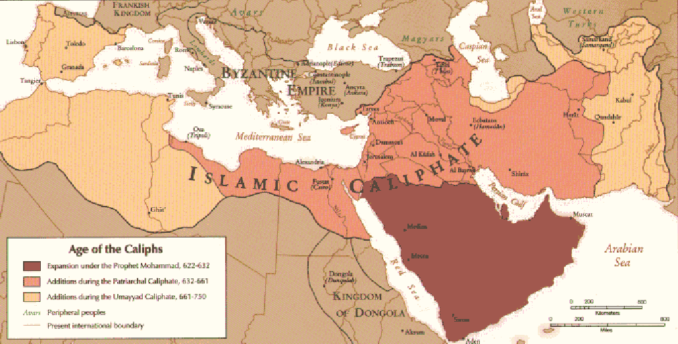

The German Reich sees as its predecessor the Carolingian Empire of Frankish kings. Its first emperor was Charles I, aka Charles the Great. His empire came into being largely due to his grandfather Charles Martel’s historic turning of the Islamic advance at Tours-et-Poitiers in 732. The Carolingian Reich was not so much owing its existence to a desire for greater European unity and integration as the EU would like to make you believe today, dear reader. Founded in 800, it clearly placed itself in the continuity of the Roman Empire. Like the Byzantine Empire did too. The latter had until then kept the last vestiges of Roman civilisation alive in the East before vanishing from the world stage, after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, at the hand of Islamic invaders.

United States of America federal government [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The emperors’ hold on power grew weaker over the centuries to the point of being pointless, by 1806. Meanwhile, other regional powers consolidated their domestic bases, sometimes ruthlessly as was the case with Prussia. This kingdom arose, in 1701, from the union of Brandenburg and the Duchy of Prussia, in 1618. Through warfare and dynastic marriage, it amassed larger and larger stripes of land along the Baltic coast, finally stretching all the way from what today is Russia and Poland to The Netherlands.

The Hohenzollerns’ main rivals, the Habsburgs, ruled what was then the Austro-Hungarian Doppelmonarchie, a dynastic union of the Austrian and the Hungarian crown. Other German kingdoms, such as the Bavarian and Hanoverian, and assorted principalities, duchies and Free Cities of all stripes paled into insignificance when compared to the two dominant powers. Next stop: Prussia and Austria-Hungary making out who was top dog between them. The rapidly and quite heavily industrialised Northwest or the largely agrarian Southeast? Well we only need to remind ourselves of the American War of Secession to know how conflicts of this sort usually pan out.

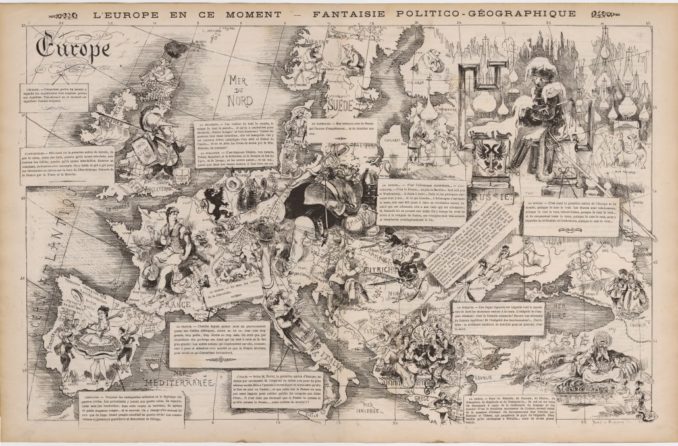

Therefore, after a few internal dogfights and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the Prussian King William crowned himself German Emperor. And to add insult to injury to the French, he did so in Versailles. This was the birth of the Second Reich.

We can briefly pause here to reflect on what has happened so far: by the end of the 19th century, the threat of an Islamic invasion of Europe was at an all-time low. The western advance of Islamic armies had been halted in 732, at Tours-et-Poitiers. They subsequently were driven from the Iberian Peninsula over the next five or six centuries. But their eastern advances, continuing up the Balkans after the Fall of Constantinople, were halted twice at the gates of Vienna: in 1529, and decisively in 1683.

France had become the major power on the continent and had remained dominant for many centuries. But after Napoleon’s foray into Moscow, France quickly became inconvenienced and defeated, first at Leipzig (1813), then decisively at Waterloo (1815). After the French Revolution, the Congress of Vienna and the Napoleonic Wars were finally over, France had lost its former great power position mainly to Great Britain. While the British Empire saw itself as a global trading empire, uninterested to involve themselves in Continental affairs but interested in keeping the peace between what looked to them like squabbling halfwits, regional powers arose in its backyard. In Germany, mainly Prussia – having militarily “unified” those bits of Germany that stood in the way of their ambition (War of German Unification, 1866, against Denmark, Hanover, Saxony, Bavaria).

German nationalism of the Second Reich was the result of ruthless Prussian imperialism, cunningly executed in the name of “nation building” against smaller German states. And of course, of their victory over the Second French Empire in 1870/71. It might have been a triumph of Realpolitik, but it came at a price. For beyond its Imperial façade, there was little holding Germany together from within. Except perhaps music and culture, hence the desire to be regarded as a Kulturnation, a nation of culture.

Yet, there seemed to be precious little shared heritage or identity holding the divergent national or regional identities together at the national level: Saxons remained Saxons, Bavarians Bavarian and so on, until Bismarck introduced the modern welfare state in 1883. This was meant to combat the rise of socialism, as it would take a lot of wind out of its sails. But it had consequences that were perhaps unintended at the time. Because to later generations, the welfare state proved to be a lot more unifying in terms of German identity than all of the Brahms and Goethe combined.

We know how the Second Reich ended: after hardly fifty years, it fell apart. Not without causing one of the three major catastrophes of the 20th century, the First World War. Ironically, it ended where it began. In Versailles, where the Kaiser’s grandfather had once crowned himself emperor.

The First World War ended without an Allied soldier having set foot in Germany. The Reich admitted defeat, accepted sole culpability, agreed to pay reparations, lost a fair percentage of its territory and saw its industrial heartland, the Ruhr valley, occupied by France. At the time, in 1918/19, this was standard procedure for a country which had just lost a war it had started.

After the Kaiser’s abdication, cabled from his Belgian exile, the Reich was also, for the first time in its history, to become a democratic, self-governing nation. For this, Germany proved particularly ill equipped morally and mentally. Over the next ten to fifteen years, the Weimarer Republik quickly descended into a dogfight between the two warring factions of socialism. National socialism prevailed over international socialism. Despite all propaganda efforts to the contrary, this mainly happened to most German citizens’ content. And we all know how it ended: with another World War and the Holocaust. This time, a full-on military occupation was required to rid the heart of Europe of German exceptionalism and to make sure that democracy finally took hold there. Up until German reunification, after events coming to a head in 1989, this Allied intervention proved quite successful.

We shall continue in part II.

Cornell University Library [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

© Guardian Council 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player