How popular is Putin really?

Before trying to answer this, a bit of background is needed. The political landscape of Russia is not really comparable with, say, Britain or France, where the mechanism of democracy pivots every few years on a clear left-right (or globalist-antiglobalist) axis. Post-Soviet Russia by contrast has been dominated by a single party, United Russia. The second-largest party, albeit far behind, is the rump Communist Party. So there is no real opposition to United Russia, which is, as the name suggests, a nationalist-lite, big-tent party. It is headed not by Putin but Dmitry Medvedev. Putin is outside it, an independent fully supported by United Russia, but free of the constraints of party association. (The West’s pet, Navalny, never really achieved mass support, was not trusted because of his foreign links, and anyway is no longer with us).

So is Putin the “dictator” the tabloids would have you believe? Or is he a democratically elected leader? Below are the views on this of four ordinary but engaged Russians I met on my travels, Ingrid, a hotel receptionist and English teacher, Sergei, a lawyer turned teacher, also with excellent English, Leonid, a software engineer, and Yevgeny, a salesman.

It’s actually a hard question to answer. All of them agreed, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, that Putin probably does have genuine majority support. However, Yevgeny the salesman said the 86% support rate claimed by recent official polling is wildly exaggerated. He thought it was more like 60%, if that. As to whether elections are free and fair, Yevgeny was again sceptical, stating that pressure is exerted on public-sector employees to vote in a certain way. The ex-lawyer Sergei and Leonid, the software guy, disagreed, saying, yes, though elections were not 100% clean, they did broadly express the popular will. Obviously, a sample of four vox populi is not much to go by, but these views did sound representative. And they underscored something I was told multiple times: Russian society is now badly divided.

Several factors have shored up Putin’s support. Even those who oppose him, traditionally the students and intellectuals, have been sucked up by what Leonid called the “rallying effect” of the war. At its outbreak, there were protests in St. Petersburg. But now that so many families have members in uniform, street protests would antagonise both the government and the people, and very probably would not be tolerated now. And though most keep their heads down, some people have a real sense of mission about this war. In Moscow, an activist stood outside the Duma with a tee-shirt saying “The homeland is in danger.” In St. Petersburg, I passed a big fellow wearing a tee-shirt that proclaimed “Bog s’nami” — God is with us.

The unpopularity of the West also helps Putin. Unlike in Eastern Europe, the West is generally — rightly — seen as inherently hostile. There is a feeling that, in the abject 1990s, America exploited Russian weakness and continues to work against it. Yeltsin is seen as both a drunken buffoon and an American-boot-licker who used Clinton ex-officials as campaign advisors. Russians are a proud people and do not like to see their leader making a dick and a stooge of himself on the world stage. Yeltsin’s antics gave weight to Putin’s claims that the West is only interested in getting its hands on Russian resources. And when naive and frankly stupid Russophobes like Kaja Kallas, the EU “foreign minister,” publicly intimate that it would be a good idea to break up the Russian state, this further consolidates Putin’s position. Kallas is effectively a Putin asset now.

A less obvious element of Putin’s support is simply fear of what would happen if he were gone. I was asked by the ex-lawyer Sergei if I had heard of Black October. Vaguely, I said. Black October was a bloody ten-day battle between opposition parliamentarians and Yeltsin in 1993 in which over 140 people were killed in street fighting. Yeltsin ended up bombarding the Duma building. The significance of this was downplayed in the West because Yeltsin was the “good guy,” but the potential for chaos that the episode revealed was never forgotten by Russians. So when Prigozhin led his convoy of armoured vehicles out of Rostov in 2023, Moscow-bound, many Russians shuddered. Despite the outward solidarity, “there is a real fear of civil war,” the receptionist Ingrid told me, and this, paradoxically, is also a factor reinforcing Putin’s control of the country. (A similar dynamic, by the way, long bolstered Communist rule in China).

Finally, it is a well-known trope that the Russians like a strong leader. In my experience, this is true, and Putin does fit in with this long-standing tradition in Russian history.

A related question was to what extent the Russian media are propaganda. Again, answers varied. The receptionist Ingrid said the news certainly was, though “some of this is now the normal propaganda you get in any country at war” — no combatant country showcases the enemy’s successes. Her views carried particular weight because she dealt at her hotel lobby with soldiers on leave. “The TV makes it sound like a picnic, but the men tell me it is not like that, a lot of people are getting killed, and it is a very cruel war.” Two of the others, the software guy and the ex-lawyer, accepted that propaganda did exist, but said it was not much worse than in the West. Both had travelled.

Ill-equipped as I am, I want to add a few comments of my own here. Russian TV and newspapers are pretty much the same as in the West in format and style — sophisticated now, far removed from the crass red-banner propaganda of the USSR (and I think of China today). A typical evening war update on TV will show footage of a drone homing in on its target, with the camera cutting away just before impact, and then immediately after an interview with front-line soldiers involved in the action. It’s factual reportage, not North Korean-style bombast. But from only one side, and as far as I could tell, purged of bad news.

The sidekick of propaganda is of course censorship. This was, again, hard to generalise about. Most English-language western news sites (including the BBC) are blocked, but not all: CNN and the Guardian, neither of which are friendly to Putin, were still available online, as were many other big European-language media. Youtube, perhaps now the primary news source, was blocked, as were all its upstart competitors. Overall, though, the censorship effort seemed a bit half-hearted, and was not nearly as thorough as Chinas’ firewall, which really does isolate you completely from western media. And you could access and even comment in the fount of all political truth, the website Going Postal.

I was told the war is discussed freely on panel shows, but overall it seemed slightly downplayed in legacy media (I cannot speak for online media). Not ignored, much less glorified, but treated more as something nobody much wanted to dwell on. In a big book shop in central Moscow, I could not find a single volume, not one, on what is by far the biggest event in modern Russian history. I saw no input from the Ukrainian side in any programme. As far as I could tell, nobody on air or in print questioned, or dared to question, the fundamental justification for the invasion.

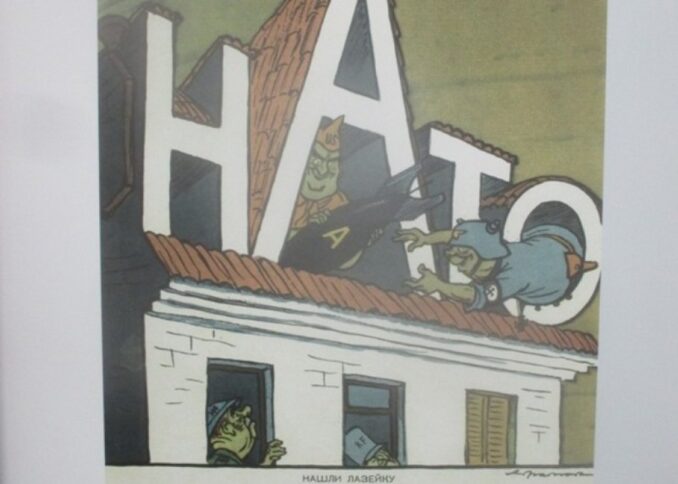

There is one ubiquitous propaganda medium in Russia inherited directly from Soviet times: public placards. In Arbat, Moscow, these depict, for example, the defacing of Soviet liberation monuments in Eastern Europe, under strap-lines like, “The gratitude of Europe.” In Nevsky Prospekt in St. Petersburg were placards demonising NATO: one showed a Nazi passing on A-bomb technology to the Americans, with the subtext that the underlying aim of both was the same: conquering the USSR. Another placard in a park highlighted the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum, an international group set up by a Ukrainian restaurateur with the aim of dividing the Russian Federation up into a dozen or so chunks — fringe fantasy, but more grist to Putin’s mill, I suspect. Most park posters, though, were simply historical, reminding Russians of their heroes. Heroes of the past, and of course models for the present.

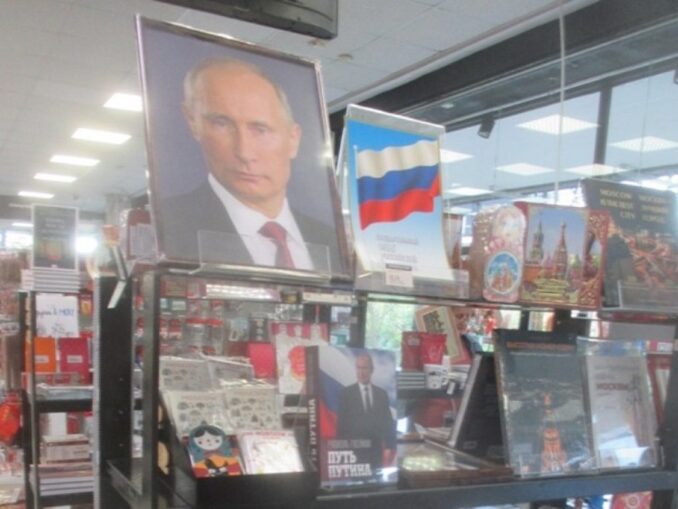

In that connection, there is unquestionably a modest cult of personality around Putin. It takes the form of jokey macho Putin T-shirts, along with sober photo portraits and Putin calendars. During a Far Eastern conference, you could not channel surf without finding him on at least one show at any given time. TV one evening showed members of a “Putin volunteer brigade.”

By far the most potent propaganda, if that is the word, is the big army recruitment posters found in railway stations and the Metro, and at major road junctions. These are so positioned that you are unlikely to not see at least one every time you go into town. A particularly effective image, hung over the long, slow escalators of the Metro, shows a soldier cradling a gun, with the words: “Moe delo,” my task, what I do. Some interchange stations now have little recruitment corners where men can sign up on the spot. The prevalence of these posters suggests, by the way, that the Russian army is indeed seriously short of men. The red-star background, by the way, evokes the USSR.

So, in sum, yes, Putin probably is supported by the people, but not overwhelmingly and not wholeheartedly. There is much propaganda, but it is not as crude and inescapable as it was under Communism (and still is I think in China). Nobody I spoke to complained that they could not speak freely; one pointed out that the disappearance of Western media was not only the Kremlin’s work. Despite the lack of access to much of the supposedly “free” media of the West, I did not find people ill-informed about the war, much less brainwashed. I’ve lived and stayed in properly repressive societies. This did not feel like one.

Unlike most westerners, Russians are fully aware of the complex historical background to the Ukraine conflict. They are not stupid. They can see the greater game, the long-term ambition of NATO to surround Russia and deny it ocean access by taking control of the Baltic and Black seas (through Turkey, Romania and, one day, Ukraine) and by incorporating the old Soviet underbelly, starting with Georgia, thereby also driving a wedge between Russia and China. They are fully aware of the vulnerabilities created by the botched breakup of the Soviet Union, which created a host of border tensions and conflicts that powers (including Russia itself) inside and outside each newly created country could exploit. Many see this as the real starting point of the Ukraine conflict. For this reason, the ex-lawyer Sergei said, people had long been expecting a major war to break out one day. People view the struggle not through triumphalist or wrathful eyes, but with resignation.

Four centuries, four invasions

Let me finish with a few observations of my own, this time on Western propaganda.

The idea that Russia is out to conquer Europe is so stupid, it is tiresome to even have to comment on it, but since senior Western politicians are seriously propagating this lie, I’m going to weigh in.

High on a building at Komsomolskaya (Three Station) Square in Moscow is a sequence of four engraved dates: 1612, 1812, 1918 and 1945. Two of them you will understand instantly. But 1612 and perhaps 1918 are not so transparent. 1612 was the year the Poles were expelled from Moscow after their two-year occupation following their invasion of the then Tsardom, and 1918 was the year of Operation Faustschlag, a last-ditch German annexation of the Baltics, Belarus and Ukraine in the closing days of World War I, when Russia was exhausted and impotent.

That averages out to one major invasion of Russian lands per century (the Ukraine had effectively been part of Russia since 1654). So, unsurprisingly, Moscow’s primary geopolitical concern for all that time has been the security of the western border. And that was perhaps the true point of the Soviet bloc. It was not so much an empire as a buffer zone.

During the whole period of the Soviet Union, the Communist bloc remained in a defensive crouch in the European theatre. They considered themselves the weaker side, and this thinking ran from the top to the man in the street. I can’t remember the number of times I was told this when I was out there, in the Eastern bloc and the Soviet Union. There never was any intention to “invade the west” (though the USSR was not averse to interfering in other regions if expedient). The main strategic aim of the Bloc was simply survival, in a profoundly hostile environment.

Today, that profoundly hostile environment is still there. So Russia still girds itself, and, like the hare of folk tales, still sleeps with one eye open. The annexation of Crimea, a response to the Maidan upheaval, caused understandable fear and dismay in the West. But in this complicated case, the Russians were welcomed. The situation with Europe is completely different. The last thing Russia wants is to again be a resented occupation force. The idea that Russia is just busting to annex Poland is as ridiculous as its own claim that Ukraine is run by Nazis. But that’s enough on this complex and tragic war.

The final part of this series will look backwards and forwards, at how the Russians today view the Soviet Union, and what the future may hold.

© text & images Joe Slater 2025