Holiday 1932

My father’s parents were married on 8th October 1931. My grandfather, Elihu, was a 25-year-old mechanic. His bride, Edith, was four years his junior and worked in a wool shop. My grandfather left the family home in Morley Street (as we found out last time, just around the corner from Lord Haw-Haw’s wife-to-be) and moved to nearby Adelphi Terrace, close to the Carlisle Currock depot of the Glasgow and South Western Railway Company. My father was born on 22nd December 1932. Yes, he was one of those unfortunate souls for whom one present covered both birthday and Christmas. In between times the young couple managed, perhaps as a late honeymoon, a summer motorcycling holiday. Evidence from the motorbike page of our family album suggests my grandfather struck out in his Triumph Model N with a pregnant wife in the sidecar. After conquering Shap Summit, the handlebars were pointed ominously towards Snowdonia.

Derby Square

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

The first port of call at which a photograph was taken was Liverpool’s Derby Square with a snap of the Victoria Memorial which sits at its centre. The foundation stone was laid on 11 October 1902, eighteen months after the death of our second longest-reigning monarch. Unveiled in September 1906, the completed memorial is an impressive neo-Baroque or Beaux-Arts monument. Derby Square, a significant site situated at the southern end of Castle Street, has been a host to numerous landmarks throughout history. From the early 13th to the early 18th century, it was the site of Liverpool Castle, which was damaged beyond repair in the 1640s during the English Civil War. Later, the Georgian St George’s church was erected here.

The Victoria Monument was designed by F. M. Simpson and features 26 bronze figures by C. J. Allen and includes a central statue of Queen Victoria, encircled by four groups of columns and allegorical figures representing justice, wisdom, charity, and peace. Other statues depict agriculture, commerce, industry, and education. The monument, made of white limestone with blackened bronze figures, is a Grade II Listed structure. In the background, the buildings facing the photographer have survived. To the right, the dark one with the pitched roof is Castle Moat House. Dating from 1838, this is a Grade II listed building, originally a branch of the North and South Wales Bank. On Street View, it now presents as a Reeds employment agency office.

To the left, the frontage of the lighter-coloured building is emblazed with a chisel engraving declaring it a branch of ‘The National Bank Limited’. Merged with the Westminster Bank to become the National Westminster, subsequently the branding gurus truncated the name to Natwest. The name disappeared after a takeover by the Royal Bank of Scotland but reappeared more recently after Fred Goodwin’s RBS became a credit crunch embarrassment. Currently, the premises is the Old Bank Restaurant where a sit-down curry can be had for a very reasonable cost of living crisis-busting tenner. The impressively preserved interior was conceived long before the days of workery-based de-banking and oozes safety, self-confidence, security, reliability, and permanence.

© Google Street View 2023, Google.com

Nowadays Derby Square consists of two levels, each exhibiting their own distinct characteristics which have been shaped by the presence of the Memorial and the courts complex behind the photographer. Puffins can have a look around here. Connecting these two levels are granite terraces that serve not only as a platform for the courts but also provide a lovely view of the memorial. The square is also adorned with trees, adding a natural balance to its urban setting. It is worth noting that these terraces are utilized for various events, including the annual Matthew Street music festival. The transformation of Derby Square into its current state took place between 2004 and 2009 under the leadership of the ‘2020 Liverpool’ initiative and involved numerous consultants and designers.

Continuing left, we pass down James Street where a short walk takes the visitor to the Museum of Liverpool on the Mersey port’s iconic former UNESCO World Heritage List waterfront. The part of the city lying behind the photographer fared less well as long before they attracted tourists, Liverpool docks attracted the Luftwaffe.

The Liverpool Blitz

The Liverpool Blitz refers to the heavy and prolonged bombing of Liverpool and its surrounding areas by the German Luftwaffe during the Second World War. This tragic event occurred because of Liverpool’s strategic significance as a major port, making it a central contributor to the British war effort. Consequently, Liverpool was one of the most heavily bombed regions in the UK, second only to London. The bombings started in August 1940 and carried on regularly for the rest of the year, with a particularly serious incident in November causing 166 fatalities.

The “Christmas Blitz” in December 1940 involved a series of intense raids, resulting in 365 deaths. However, the most concentrated series of air attacks occurred during the first week of May 1941, a period known as the “May Blitz”. Over eight days, Merseyside was bombed almost every night, leading to 1,900 fatalities, 1,450 serious injuries, and about 70,000 people becoming homeless. The Liverpool Blitz resulted in approximately 4,000 deaths in total, causing widespread destruction and loss.

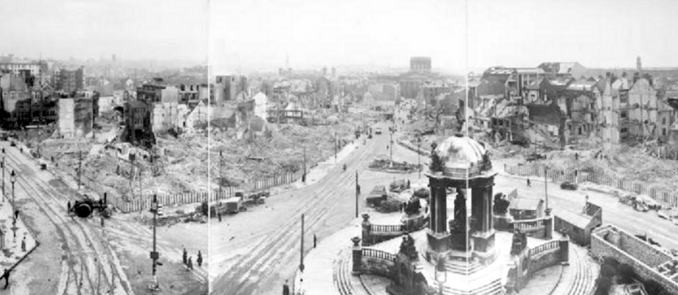

A panoramic view of bomb damage (1942),

Ministry of Information Photo Division – Public domain

In the picture above, we see the Victoria Memorial while looking south. Judging by the angle, the photographer must have been standing on the roof of Castle Moat House. The near-complete devastation allowed for an extensive post-war redevelopment which was itself replaced at the turn of the 21st century by the Liverpool One shopping, residential and leisure complex.

The layout of some of the roads has changed which doesn’t help with identification. Presumably the protruding stump above and to the left of Queen Victoria’s memorial is the part completed tower of the city’s Anglican cathedral. What can be said with certainty is that there is a traction engine in the bottom left of the photograph and that the roads are resplendent with tram lines.

Liverpool Trams

The Liverpool trams were a form of public transportation that served Liverpool, England, from 1869 until 1957. The system began with horse-drawn trams, but by the late 1890s, electric trams were introduced. At its peak, the tram network covered a vast area, operating over 50 routes and serving many Liverpool suburbs. However, with the advent of cheaper and more flexible motor buses, the tram system began to decline. The last Liverpool tram route closed in September 1957, marking the end of an era in the city’s public transportation history. Despite this, the memory of Liverpool’s trams remains an important part of the city’s historical and cultural heritage. Known as the ‘leckies’ the final services ran on Saturday, September 14th 1957.

Nearly the end,

Dr Neil Clifton – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Family connections

The Derby connection refers to the Earls of Derby, a title in the peerage of England conferred to the Stanley family in 1484. Their ancient seat is Knowsley Hall which lies in 2,500 acres of parkland that begins just as the suburban sprawl of Liverpool ends at the far side of the M57. Interesting members of the Stanley dynasty include Lord Stanley of Preston, the Governor General of Canada in 1892, after whom ice hockey’s Stanley Cup is named, and Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, the longest-ever serving leader of the Conservative Party and the abolisher of slavery in 1834.

Opposite Knowsley Hall sits the West Derby district of the city which includes the West Derby Cemetery where my grandfather’s older brother, John, is interred. Seventeen years the elder, John was injured during grenade practice while on active service in 1917 with the London Scottish Regiment. He returned to his wife in Liverpool and died of his wounds the following year. Puffins can read more here, and here.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Perhaps the newlyweds will have visited the grave, perhaps not. The war grave photograph is not contained in the family album but within an accompanying envelope of loose prints. What we know for sure is that they went down to the docks. Some pictures of the shipping are present on the ship spotting page of our family album which you can read more about here (and see the Triumph N and sidecar). The presence of HMS Exeter alongside narrows the date of the visit down to June 1932 as per a report of the occasion in the Liverpool Evening Express.

Ironically, if I may indulge Puffins one final time to a previous piece, my own surprising DNA test result suggests John and Elihu’s grandfather was German. The net of that branch of my research is closing upon a dot on the map in 1860s Westmorland. At first glance an unlikely outpost for cosmopolitan Continental integration. However, those times included transient farm and mine workers fleeing revolution and economic hardship in Germany. I will keep Puffins posted.

© Always Worth Saying 2023