Last in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in February 1968 – Jerry F

We had camped that last night on the Crow Indian reservation near Hardin, a miserable camping ground with rank, dusty grass and derelict toilets and rubbish and broken bottles everywhere, for which the friendly Indians scalp you a dollar a night.

I slept badly. But dawn comes early in Montana in summer.

By five o’clock the pearl-grey mists have vanished and a hot sun is already blazing from a cloudless sky. By midday the heat is stifling.

To have to stand and fight all day in that heat — on a shadeless ridge, your water bottle empty, while down below you, tantalisingly close, wound the Little Bighorn River — must have been refined torture…

I walked, yawning, to the edge of the cottonwoods and looked south across a rolling, treeless moor.

Half a mile away the Stars and Stripes hung limp on its tall flagstaff. Just beyond it, sited on a ridge shaped like a haricot bean, I could see a granite memorial shining in the sun.

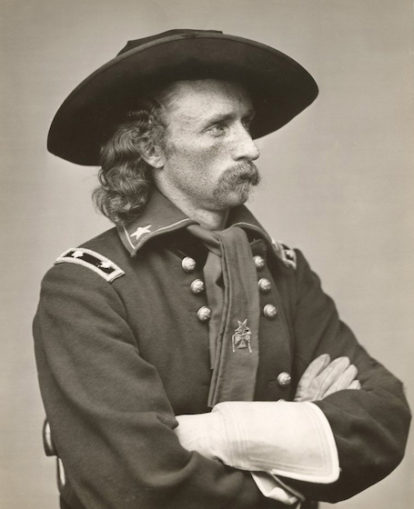

Up there on a June Sunday 91 years ago — a Sunday very much like this, windless, mercilessly hot — died Colonel (brevet Major-General) George Armstrong Custer.

George Armstrong Custer, U.S. Army major general,,

George L. Andrews – Public domain

About him, like a feudal chieftain, lay the bodies of his kinsmen, his captains, and his men at arms.

It was the end of one of the bloodiest and most futile battles in American history.

To the flamboyant, vainglorious Custer had fallen the role of leading a regiment of the U.S. Army into the worst defeat of the Indian wars, so earning for himself an immortality that victory could never have achieved.

It was a battle that should never have been fought, one in which the lives of 261 brave men were recklessly thrown away.

It settled nothing, except, perhaps, to prove that, given the choice of ground and a cause to fight for, Indians could be better soldiers than white men.

Yet today a square mile of that battlefield is preserved for all time as a national cemetery and a national monument.

It is preserved exactly as it was. Scattered across it, far out and around that fatal ridge, are forlorn white markers.

Each white headstone covers the exact spot where the body of an American soldier — stripped, scalped, horribly mutilated — was found on the morning of June 27, 1876.

As you climb to the ridge the headstones become thicker, until very near the top there are 56 of them all together, standing back to back.

Over one, near the centre of the ring, flies a small blue and red flag.

Here they found Custer’s body, naked like the rest, two bullet holes in the chest but the famous yellow hair unscalped.

Now Americans are not unduly impressed by their own defeats. And I would have thought they would have preferred to forget the disastrous affair of Custer’s Last Stand at the Little Bighorn.

Yet every summer’s day a long queue of cars makes the pilgrimage up U.S. Highway 87 to the ridge above.

People park their cars just outside the neat little museum to stare, round-eyed, at Custer’s famous buckskin campaign suit, at his Civil War trophy sword, its Damascus blade inscribed with the legend: “Draw me not without cause. Sheathe me not without honour.”

They pore over the historic last dispatch, scribbled by his adjutant in panicky haste calling for the help that never came and are fascinated by rusty rifles and scraps of equipment picked up on the field.

They sit down on tubular chairs before a huge panoramic window which frames a wide-screen picture of the battlefield while a severely precise young man in a Boy Scout hat explains what happened on those two hot summer days 90 years ago.

He points behind him to the distant line of the Rosebud Mountains, where only ten days before — but unknown to Custer — the Indians had defeated General Crook.

They follow him, breathless, as he points into the middle distance, to the woods along the river line, where was the Indian village Custer had vowed to destroy — by sending to his second-in-command, Major Marcus Reno, to attack it from one end while he sealed it off at the other.

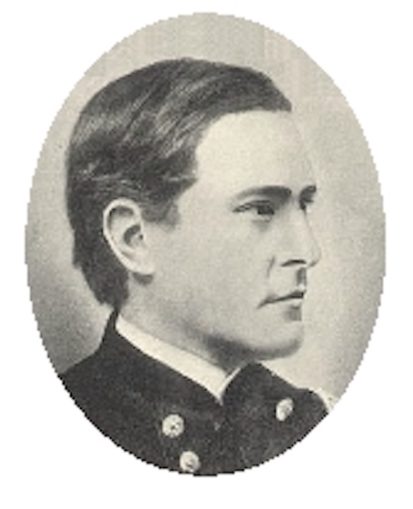

Marcus Reno,

Unknown photographer— – With copyright holder’s permission

He shows them the very spot where Reno and his three troops of the Seventh Cavalry ran into more Indians than they had ever seen in their lives, stopped to fight, panicked, and retreated across the river in wild disorder.

They follow his finger up the bluffs above the river to the treeless hilltop where Reno and his survivors, joined later by Captain Benteen and the reinforcements that should have gone to Custer, held out for nearly two days, suffering horribly from thirst.

Finally, the young man’s finger swings casually in a five-mile arc to the ridge where Custer and his five troops, driven back and back by Crazy Horse’s blitzkrieg, out of sight of the rest of the regiment, made his last desperate stand.

Dryly, as if explaining a problem in geometry, he points out the treacherous gullies, deep enough to hide a man, up which the Indian snipers crawled to rain down arrows like mortar fire on the defenceless men crouching behind their dead horses on the ridge.

Then, quietly, almost without a word, in their gay beach shirts and baseball caps, the sightseers drift off in twos and threes to see it for themselves.

What then — I kept asking myself — is the morbid attraction of this bleak and blood-soaked place? Undoubtedly the biggest attraction must be the personality of George Armstrong Custer himself.

Bone-headed braggart that he was — hated by as many of his men as those who loved him — shameless careerist, he was a heroic figure.

His record in the Civil War — which he had finished as the youngest general in the Union Army — proved that.

And throughout the Army “Custer’s Luck” was legendary.

But Custer was under a cloud at the time of the battle. His whole career was in the balance.

At the Little Bighorn he recognised a neck-or-nothing chance to win back some of that glory he loved so much.

His orders were plain enough — he was to wait for his superiors, Terry and Gibbon, on the 26th and attack with them under their orders.

Instead he made a forced march of 83 miles in 24 hours and went in alone on the 25th.

So he flagrantly disobeyed orders, ignored the warnings of his scouts, pigheadedly refused to take with him the two horse-drawn Gatling guns that might have made all the difference, arrogantly declined the help of old, crippled Major Brisben and his four troops of the Second because he, Custer, wanted it “to be a Seventh Cavalry battle.”

So splendidly, superbly, recklessly, bravely, he led five troops of the finest fighting troops of the U.S. Army to death.

Then there is the mystery that has hung heavy over this battlefield for 91 years.

What happened to Custer and his 200 after he was last seen waving his hat gaily as he watched Reno go in?

We don’t know. We probably never shall know now.

There were no American survivors and few of the Indians ever talked. Certainly Custer didn’t die, sword in hand, as most painters see him, for sabres were not carried by cavalry in action in 1876 and Custer had left his in barracks.

But did Crazy Horse and his Indians make a last charge at the end?

Did the Indians have up-to-date firearms? There is evidence that some of them were better armed than the cavalry.

Was Custer the last survivor? Probably not. Finally, was he left un-scalped, according to the hard-dying legend, because the Indians respected him as a hero? Possibly.

But he had had his golden locks close-cropped just before the battle. And, anyway, the Indians hated him.

They called him ‘Squaw Killer” because of his brutal massacre of their women at Washita.

Perhaps, after all, it was the senseless courage — those gallant 600 white men against 5,000 whooping bloodthirsty Indians — that draws the visitors here

A modern motor road takes you the five miles from Custer’s ridge to the semi-circle of exposed hilltop where the remnants of Reno’s battalion, routed, exhausted, desperately short of ammunition, and dying of thirst, held out for two dreadful days and a night.

You can see the slit trenches they scraped with anything they had; with hatchets, knives, even mess kit.

You can see the deep ravine to the river down which the water carriers crawled under fire to bring a kettle of water to ease the wounded.

Poor Reno! A brave man with too much imagination to die a hero. Had he galloped after Custer, he, too, would have died a hero’s death with all his men around him.

Instead he stayed where he was and saved what was left of the Seventh Cavalry.

History did not forgive him for that. His life was ruined by the shambles of the Little Bighorn.

For the rest of his service career he was followed by taunts like that flung at him by Lieutenant De Rudio at his court-martial: “If we had not been commanded by a coward we would all have been killed.”

Under the strain he slowly disintegrated. In 1880 he was court-martialled yet again — this time for a brawl in a bar room — and dismissed the service. He died in misery and poverty.

It was only last year, nearly 80 years after Reno’s death, that the United States Army Board of Correction of Military Records posthumously reinstated him.

On an appeal by his great-grand-nephew and the American Legion, the Board changed the records to show that Reno was honourably discharged instead of dishonourably as previously recorded.

This decision cleared the way for Reno’s body to be re-buried in a place of honour near that of General Custer, the vainglorious, brave idiot who was given a hero’s burial at West Point.

Over this barren moor his spirit rides flamboyantly into immortality.

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023