Eighth in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in January 1968 – Jerry F

We reached Cody, Wyoming on a night of driving rain and threatening snow. It was too late to try the mountain pass to Yellowstone Park. So there was nothing else for it. For the first time on this trip we had to shelter in a motel.

But at least it gave us a chance to take a detailed look at a small self-contained rather smug little town which for the last 65 years has been dedicated to preserving the immortality of the most famous American who ever lived.

And if you think this is rating Buffalo Bill Cody rather too high, you might bear in mind that there are parts of the world where they believe that Buffalo Bill is still very much alive.

Fortunately for the town of Cody, it got into the act very early. In 1895, when Buffalo Bill Cody was still at the peak of his fame, a group of far-sighted citizens persuaded Bill to make his home here and give the town his name.

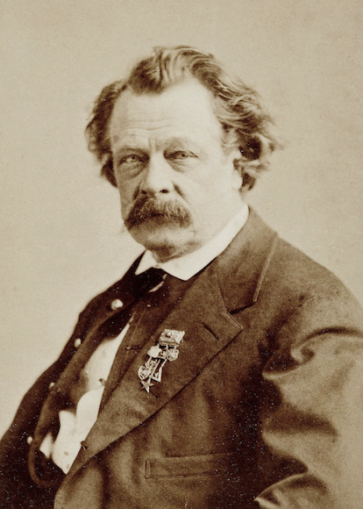

Buffalo Bill Cody with a rifle across both shoulders,

Burke-Koretke Photo Chicago – Public domain

Though there is no evidence that he ever did live here for more than a few uneasy months, give it his name he certainly did.

He rides in glory on a pinnacle of bronze at the entrance to the town, pointing dramatically to the superbly theatrical cleft in the mountains which leads to Yellowstone Park.

He presides in his own museum, where case after case venerates Buffalo Bill, the Beau Sabreur.

For 50 cents you can study the complete case-history of a hero, from the gawky 16-year-old who rode the Pony Express, to the dapper old gentleman with the white ringlets and the Vandyke beard, forever patting the heads of adoring youngsters or shaking hands with every crowned head in Europe.

So if Cody has become one of the biggest tourist traps in the West, not all the credit goes to Buffalo Bill. The city founders had the shrewd sense to site it cunningly as any Indian ambush. Tourists on their way in or out of Yellowstone Park must fall into its net.

And so it has its fake Main Street (with the falsest of false front stores), its Buffalo Stockade, its Annie Oakley Antiques, the usual cluster of plaster wigwams.

I have nothing against Cody, Wyoming, as a tourist trap. After all, it sends thousands of small boys home happy every year, even if the spurs and shotguns and bows-and-arrows they are hugging were made in Japan.

My only objection – and it is a serious one – is that it is fostering a legend that is only half true. And it is surely not fair to W F Cody who, for all his faults, was enough hero for six ordinary men, to show him as a sort of Batman in buckskin.

In Cody, Buffalo Bill is portrayed as the gentil parfait knight, sans peur et sans reproche. Which is very far from the case. Bill, a hero in every sense, had a heroic appetite for wine, women and song.

To get Buffalo Bill the Legend and Buffalo Bill the Man into the right perspective you must go back several hundred miles east to North Platte, in Nebraska, where he lived for 30 years. There they will show you the Gothic monstrosity Bill raised for his old age and named, appropriately, Scout’s Rest.

(It was just bad luck that Bill was never able to enjoy that retreat. He went broke and had to move out).

Now the place is a national monument, and a full-scale experiment is being worked out which, they hope, will discover the truth about Buffalo Bill.

It is called, simply Project 71: and a team of researchers are laboriously collecting and cataloguing and cross-indexing every legend, anecdote, truth, half-truth, and downright lie they can uncover on the Hon. William F. Cody.

In charge of this interesting experiment is Mr. George LeRoy. I doubt if any man is more fitted to the job than Mr. LeRoy. He is not only a trained historian, he is probably Buffalo Bill’s greatest fan. Like millions of Americans he believes quite simply that Buffalo Bill Cody was the most famous American who ever lived.

This does not allow him to flinch from the truth about Bill. In fact, the truth about Buffalo Bill began not very far from Cody.

It began, in fact, on a night in 1872 when a freelance journalist called Judson, who wrote under the pen-name of Ned Buntline, found Bill sleeping off a hangover under a wagon at Fort McPherson.

Ned Buntline,

Sarony, 680 Broadway, New York – Public domain

Judson, a prolific writer of pulp fiction – “Give him a pencil, a pad, and a bottle of whisky and he’d knock you out a story in a night” – says LeRoy, had come West from New York to find fresh inspiration. He found it right there under that wagon.

With the barest help from Bill, he began to pour out a torrent of “true” stories for the New York Weekly: a weekly cliff-hanger, in fact, in which the hero was always Buffalo Bill Cody.

As his fame spread and his image grew giant size, a hack playwright called Fred Meades concocted a hair-raising melodrama, “Scouts of the Plains,” out of Buntline’s frenzied prose. Bill happened to see it when it was playing the Bowery Theatre, New York, took a bow — and found his true profession.

He set up on his own account. With Buntline’s help he warmed Meades’s hash, played the lead himself — magnificent in beard and buckskin — and brought in two old frontier chums, Texas Jack Omohundra and the one-and-only Wild Bill Hickok.

Texas Jack and Wild Bill soon faded out. The stage was not for them.

It was so successful, in fact, that Bill — now calling himself the Hon. William F. Cody — put the show in a tent and took it on tour.

And that was the beginning of Buffalo Bill’s Original Wild West Show, which ran, practically non-stop, for thirty years.

And it was here, at Scout’s Rest, that he rested up after those exhausting world tours — to plan even longer and more complicated tours. It was here, too, that he wined and dined and entertained like a Roman Emperor, and, like many another famous husband, was hen-pecked and driven almost frantic by a jealous wife.

Buffalo Bill’s home, with a nice Victorian style,

Smallbones – Public domain

In the end he bought her a place of her own in North Platte, a sumptuous wooden palace called Welcome Wigwam (“Where,” says George LeRoy, “everyone was welcome except Bill.”)

But the days of glory passed. One day, in 1917, America woke up to find that its greatest hero was now a legend, in fact, Buffalo Bill had died in Denver, penniless and alone.

Yet one more triumph remained. Just before he died he sold his body to a syndicate of Denver businessmen to pay off his debts. They buried him in a princely tomb on top of Lookout Mountain, to become — after Boulder Dam — the second biggest tourist attraction in Colorado.

Buffalo Bill, the man, has been dead these 50 years. But the legend is undimmed. You catch a gleam of it at Scout’s Rest, among those dusty playbills.

Cries the ringmaster: “Buffalo Bill, the Hon. William F. Cody, will you take this stage through country infested by hostile Indians?” And back came the ringing tones of the hero in buckskin: “Sir, with God’s help — I will.”

NEXT: Home on the range.

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2023