Chief Superintendent Dager had been back in the office for the last ninety minutes, having been called by the duty team. Late and overnight duties had diminished as he had climbed the ranks, but in some ways he found it oddly comforting, not exactly a spider at the centre of the web, but certainly much closer to it than the periphery, or so he thought at the time.

If the atmosphere in the command room was not chaotic or panicky, there was a thread of tumult and uncertainty twisting its way among those coming in from their homes and private lives, among them a couple of Home Office civil servants, at least one of whom was an aide to the Secretary herself. His boss, the Command head, Assistant Commissioner Ted Armstrong, was in situ, trying to make sense of events on the ground at the NEC, and the morass of patchy intelligence reports relating to the previous killing. Dager checked himself: why had he called it a killing rather than murder? Was it because buried deep down he had a sense of pre-emptive justice rightly done? He stifled the thought.

All the subsequent reports received from those on the ground were confirming what he had told Bowson on the phone and little details kept being received to colour his bare sketch of the events of a few hours earlier. Four abandoned assault rifles, over eighty rounds fired, almost all hitting the vans. Four dead men in the two front cabs, two dead in the back of one, one critically wounded in the back of the other, all with multiple gunshot wounds. It was a miracle that neither vehicle’s fuel tank had ignited nor the estimated two tonnes of commercial explosive been detonated. Dear God, if the target was the hotel they would have reduced it to rubble.

The buzz in the offices was distracting as he studied the fragments of information like a papyrologist trying to make sense of the latest discoveries from Oxhyrnchus, not knowing whether the key fragment to make sense of the others was lying before him or still lost in the Egyptian desert. A couple of witnesses had seen two motorbikes travelling on to the motorway bridge at the nearby junction, carrying four people they thought. No other details. The relevant camera footage was being accessed and analysed already, but this was the heart of the UK road network, if that was them they could be hundreds of miles away by now. They just needed a break.

It was a feeling reciprocated by the Assistant Commissioner, joining with much darker ones after having put down the phone call from an incandescent Home Secretary. That bloody woman. Off duty officers were being recalled, resources diverted from other investigations, other agencies asked to do likewise. Why? Here he ascribed an accurate, if uncharitable, answer. The call had been received just after the late evening news’ ’What the papers Say’ slot had flashed up the tabloids’ late edition headlines. ‘SAS Foil Britain’s Mumbai in Massive Shoot Out’, ‘Islamic Loony Gang Banged Out on Motorway’ (he struggled not to laugh at that one), ’Massacre by the Motorway’. Totally irresponsible and largely inaccurate of course, but they were happier printing the rumour than incomplete facts in these situations. But worst of all were the broadsheet headings, ‘Shoot to Kill on Britain’s Streets?’ or ‘War on the Streets – Has the Government Lost Control?’ His political superiors were going berserk, demanding to know if the MOD had a rogue death squad roaming around the Midlands or, if not, why were the police not telling them that it was they who had foiled the attack?

Ted Armstrong permitted himself another rueful smile. He wasn’t too far from retirement which gave him a certain objectivity and immunity to external pressure. He liked to think of himself as old school, not an ardent careerist, and was increasingly uncomfortable at the way things were going, the unfair pressures put on younger, still ambitious subordinates.

The Prime Minister had called another COBRA committee meeting for nine tomorrow morning, which meant that the Home Secretary would want to see them at seven, just to look in control, wasting more hours of precious time in talking rather than investigating and analysing. He must be getting old and cynical. They called COBRA meetings for the slightest thing these days; it was all an illusion of control. As the state got ever bigger and more bloated it became ever more impotent, unresponsive and more desperate to pretend it was otherwise. They had hacked the police and armed forces into near impotence to fund their interest groups, and never stopped to consider why their other demented policies’ consequences were now leaving them like a giant dinosaur’s brain, unable to cope with the rapidly changing environment around them. You could sometimes almost smell the gangrenous flesh of some of its decaying extremities. Well, back to the task in hand, just try to finish with a good record and integrity intact.

‘Henry’ switched off his phones and the television news. Too much chaff to discern meaning and pattern at the moment, let others establish the facts. He needed to remain bright and alert to make the connections, come up with explanations, and play the game. His time in the military had taught him the importance of rest in times of crisis. He eased back in the bed in the single bedroom of his small flat in an okay part of London, his lack of wealth meant he couldn’t afford anything in the best areas, those which had been colonised by the trashy foreign super-rich or Croesus like financiers. He found he had less and less need for money: life on his own had its compensations.

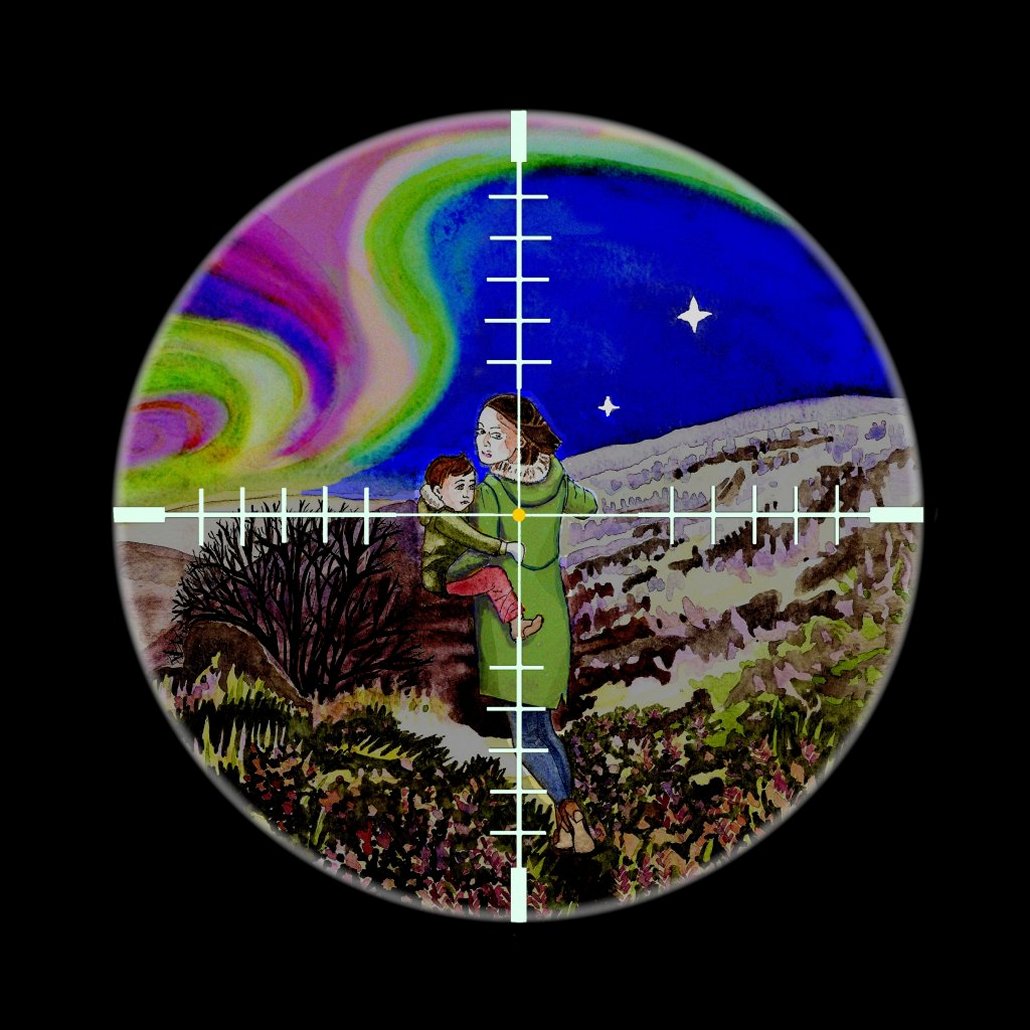

The train of thought carried him back through the years. He knew where it was taking him, he didn’t want to go, but was powerless in the face of the longing that was its engine. His first Bosnian tour as a subaltern in a rifle regiment, based near Banja Luka in the last months of the raging conflict; the Serbs were on the slide now. His patrol, his little command, two Warrior APC’s and an armoured car detached from a cavalry regiment. Both regiments had gone the way of all things flesh since; curse them, cutting him off from something that might have been a family. Twenty men and him, rumbling up to the outskirts of a small village, dust kicking up all around from the tracks, the armoured car in the rear. Traversing their turrets left and right, watching for snipers, peering through their apertures for hints of roadside bombs. A shot up ahead. A small group of armed men in combat gear, looking at a body in the dust at their feet, pointing at something in the ditch by the road. They pulled to a stop twenty yards behind them.

He dismounted, taking three of his boys and his interpreter through the rear door. His sergeant, still one of his best friends to this day, was in the turret ready to bring down covering fire, the other vehicles, as they had practised, covering left, right and behind. He walked up, Bosnian military uniforms he noticed: his interpreter became agitated, “Chechens” he whispered, “a couple of Bosnians as well.”

He stiffened; he knew the Chechens’ reputation, the worst of the worst for unpredictable brutality. Show no fear was his first though. He could see his sergeant wasn’t happy about it at all; he had seen it all before, this was his third tour in this hellhole already. The body was that of a young boy: fourteen, maybe fifteen, lying in the dust with his own blood congealing beneath him. One of the guilty men reached down and pulled something gold from the corpse’s neck, wrenched it free and showed it in triumph to his colleagues, but they were more interested in the cowering figure at the bottom of the ditch. Filthy, plastered with mud and dust, terror seemed to radiate from her, unnerving him. She must be older than the dead boy on the road top, sister, wife, girlfriend it was difficult to tell. A couple of small back-packs were lying beside her, half protruding from the brackish ditch water. The gunmen were ignoring him quite pointedly.

No, no, please don’t take me there. Not tonight. He knew what they were planning; you could read it in their body language. He nodded to his Sergeant and five more of his men from the Warrior dismounted and strolled up towards them, their safeties were off, he knew. Keep your own hands away from your weapon, cool it down.

He had now got their attention. There were seven of them. He pointed to the crouching girl and beckoned to her. They didn’t like it he could see, their voices started to rise, his interpreter began to translate, but he cut him off. “I’m not interested in what they’ve got to say, tell them that’s the way it’s going to be. We have the numbers.”

Something in the flat way he spoke seemed to have more effect than the words repeated by the translator. Grumbling and scowling they made to move off. By instinct alone, despite himself, he reached forward and put a hand on the gold chain that the looter had pulled from the corpse moments before. The man made to pull it away, another moved his gun, and then caught site of the weapons trained on them, causing him to release it into his grasp. It was an orthodox crucifix and chain. They tramped off up the road muttering, covered by his men.

He was moving purely instinctively now, some deep human impulse brushing aside his professional training and the will emanating from his men not to do anything silly. He stepped down into the ditch and reached out towards her. She was utterly terrified, filthy in smock and torn jeans, quaking, looking at him through lank muddied hair plastered across her face. Seventeen, five or six years younger than me perhaps? She shrank back. He smiled gently. Her eyes slid over him, alighting on the Union flag on his uniform. He reached towards her. She let him, didn’t resist when he lifted her into his arms. She was trembling now, wetting him with the new tears that were starting to pour. She was as light as a feather, malnourished for sure. He tried to pass her up to one of his boys on the road top three feet above, but she clung all the tighter. In the end, it took three of his comrades to lift and pull both of them out together.

He had nodded to Jonesy, the Sergeant. “Let’s get back and get her to the field hospital, recover that poor sod, and their bags.”

Top man Jonesy, it all just happened; they turned around and headed back to base. He was inside the transport now; she was clinging like a limpet, not answering the gentle questions of his interpreter. Shivering, sobbing quietly, plainly fearful of being in the belly of this beast of war, holding on to him as if her was her one chance of re-emerging into God’s light. Jonesy sat beside them.

“Bad business Sir, Orthodox, almost certainly Serb refugees, the poor devils.” He was looking at the crucifix twisted around his boss’ hand. She caught sight of it and touched it, the tears rolling again. He pushed it into her hand where her fingers enclosed it like a Venus flytrap.

The ride back in the vehicle was tomb-like, only punctuated by staccato radio conversations and the mechanical noises all around them. The boys kept glancing at him, weighing him up, their natural black humour stilled, almost as if they were at the graveside of the young lad in the body-bag secured on the outside. Jonesy told him years later that some of them, those on their first tours here, thought him mad, others reckless. One had even leered a joke and been struck down by a comrade. Hard bitten, foul-mouthed, cynical, they were all of that, but he was learning they were so much more. What was it George MacDonald Fraser had said in his memoirs about the Burma campaign with the Cumbrian regiment which he had read so avidly over the years? Ah, there it was, ‘Whenever I think back on those few minutes when the whizz-bangs caught us, and see those unfaltering green lines swinging steadily on, one word comes into my Scottish head: Englishmen.’ He was still a romantic at heart he knew, but it was true also of many of his boys, especially the veterans whose tenderness was nearer the surface through exposure to, well, Hell.

He had had to carry her, still clinging to him, to the old warehouse that counted as a small field hospital, one of the guys bringing the recovered packs along behind with the interpreter. They had a devil of a job persuading her to release her grip, she screamed and wept, distraught beyond reach. They sent for the local Orthodox priest to see if any of the locals knew her. The presence of the nurses seemed to slowly still her, helped by that of the priest, and she finally relented when he promised to return at the end of his watch. He left her cradling the crucifix as if vampires were all around her.

He debriefed and went to see Jonesy. “You did the right thing Sir, if I may say so.”

No, stop there, no further please. Please have pity. He had returned at dusk. He was intercepted by the Sister just outside the women’s ward. They had cleaned her up, re-clothed and fed her. She seemed to speak very rudimentary English. She was called Jovana, he had later learnt it meant ‘God is gracious’. The irony had struck him hard; He certainly hadn’t seemed to be in her case: she had been brutally raped some time ago and badly beaten. The boy was her younger brother, sole survivors of a family of Krajinan villagers ‘ethnically cleansed’ from their ancestral home by the invading Croat army. They had been fleeing to some distant relatives they thought were in Banja Luka when they fell in with her brother’s now murderers. Their bags contained all they had in the world, little enough and the crucifix that had belonged to her mother was probably the most valuable thing she now possessed. All this the priest had discerned before going to find her relatives.

“The doctor said she may never have children now, but will need a proper scan and tests in a modern hospital to tell.”

Why had the Sister said that, was she looking at him oddly? He went through and sat beside the girl, not sure what to do or say. He knew no Serb at all other than please and thank you really. She looked up at him, as if unworthy, afraid. He smiled, “Jovana?”

Her face was impassive, no trace of the unbounded emotion she had displayed earlier today. She was quite pretty, dark shoulder-length hair, grey eyes, very slight of build. It came as a surprise. She seemed to be weighing him up. It was unnerving; she must still be in deep shock. She pushed out her right hand into his and placed something warm and hard within his palm. He looked down; it was the crucifix and chain. Her cracked lips moved, “Life… gift? Thank you for…”

He had looked up at her and been sucked over the precipice by the vortex of her utter vulnerability. Yes, that had been it, not desire, not admiration; they had come later, just that vulnerability against which he had no defence. The desire to protect was his crowning weakness, the spur to his flank. No more please? I need rest. But he knew there would be no respite, he had been here hundreds of times. The chained crucifix round his neck was cutting into his chest, just as his memories of her sliced into his mind.

He had gone to see her every day, twice a day when possible, a practice he continued after she went to her relatives’ home. They were dutiful towards her no more; she was a burden and an embarrassment. And then, suddenly it seemed, his tour had ended and back home he went. His relationship back home fizzled out within days, his thoughts elsewhere. A fortnight later he took leave and flew back to the Balkans breaking the rules and working on autopilot, using his contacts still in situ, carrying a small box. He returned, to the consternation of friends, family and colleagues a husband, then spent the next six months bringing her home.

Nine months of true joy followed, perhaps the only real happiness he had ever known. The doctors confirmed there would be no children and then found something else; the real nightmare began, the relentless, pitiless spread through her body, possibly, they thought, triggered by the trauma. Temporary victories raised hopes, only to be crushed by subsequent tests. And then she was gone, to him another casualty of evil. She never cried, never complained about anything after he brought her back, as if put beyond mental anguish by her earlier experiences and the intensity of her bond with him. That was the only consolation he could take. He had been lost, bereft, drifting, investing his entire persona into his military and subsequent careers, until events had catalysed something in him that had been lying dormant since her passing. Is that it? Is it over for tonight? Have mercy. And then the sounds of the River Lethe washed over him for a few short hours. One day, one day, it would be the waters of the Jordan instead, perhaps then he would be with her again.

© 1642again 2018