In a previous edition gleaned from my family’s 1950s road trips album, from the top of the Eiffel Tower we noticed an interesting double-decker bridge carrying both a road and a railway across the River Seine. The upper part of the magnificent Viaduc d’Auteuil, also known as the Viaduc du Pont-du-Jour, belonged to the Petite Ceinture line, a circular rail route built to supply Paris’s 1845 fortification walls and to transport passengers and goods between the city’s major rail termini.

With modern aerial photography we were able to follow the existing and partially interrupted trackbed almost as far as Gare de Austerlitz. From Austerlitz it is a short hop across the Seine, near the present-day Pont National in the Bercy district, to Gare de Lyon on the opposite, eastern, bank. A chord on either side of the river connected gares Austerlitz and Lyon to the Petite Ceinture. It is at Gare du Lyon that we begin this week’s photographic family adventure. Previously I accidentally followed in my father and grandfather’s Ford 8’s footsteps from Austerlitz to Biarritz, Madrid and Gibraltar. The album has reached 1955 and another journey to Switzerland. Three decades subsequent to that, I followed their Ford Prefect south and west during my previous life more interesting having been drawn from Paris and tasked to Geneva.

In my day, four decades ago as opposed to my grandparent’s seven, Continental railways were on the cusp of great change. Too many years of decline were about to be reversed by a new series of high-speed railway lines the first of which was the SNCF’s Ligne à Grande Vitesse from Paris to Lyon. 167mph Train à Grande Vitesse (TGVs) branched from the high-speed line to the original ‘classic’ lines to connect various destinations, including Geneva.

Not always a good thing. Some of us prefer to linger in the dining car or make new friends in a slam-door compartment on a lengthier journey. Better still, sleep overnight in a cheap as chips couchette and avoid a hotel bill.

Early on in this brave new world, I was horribly caught out. My French isn’t great and, it being a Parisian Friday evening, I might have been slightly refreshed by the time I reached the ticket office at Place Louis-Armand. Reference to an old Horaire SNCF in my derring-do box reveals a big circle around the 19:13 service from Gare de Lyon to Geneva. Named the Jean Jacques Rousseau and carrying symbols for a dining car and bar it began to waddle and quack like a sleeper train. The supplement I was charged I (wrongly) assumed to be for a bunk. Unfortunately, the extra fifty Francs allowed for a crack express via the high-speed line which whisked me non-stop to Macon in record time before addressing the windy, twisty old line to Genève Cornavin. Arriving at three minutes to eleven necessitated, for once, spending my subsistence on subsisting (in a hotel full of Arabs) rather than just trousering it. Grrrr.

Looking through my old maps and timetables, Gare de Lyon to Macon is 211 miles via the high-speed line and I departed Macon at 20:56. We shall assume arrival was at 20:54 which makes 101 minutes at an average of (211/101 miles per minute, *60 for mph) 125 mph point to point. Way short of the top speed because, as every Puffin knows, acceleration is inversely proportional to the net force applied (ie tractive effort) so it takes forever to reach a higher maximum speed. From Macon to Geneva is 92 miles and was timetabled for 2 hours and 1 minute with 3 intermediate stops. A point-to-point average speed of (just divide by two this time) 46 mph which proves the utility of a lengthy high-speed line with no stops.

Thereafter I was more careful and when returning to Paris made sure I got on the right train and had a more economic and entertaining night. The couchettes were mixed and, as every travelling English gentleman of a certain generation will be able to recall, there is a law of nature regarding older female Gallic sophisticates and the younger brutish no-matter-how-well-mannered Anglo-Saxon male. Suffice it to say, French ladies of a certain age maintain the vitesse and sleek lines of a high-speed train while, a friend tells me, still being capable of bouncing like a cement train derailing in a tunnel. Whatever that means.

Arrival at Gare de Lyon was suitably early allowing, in the days when such things were allowed, a wander along deserted platforms taking photos of the trains. You’ll have to trust me when I say I have a picture of an entire morning’s TGVs, orange in those days, spread across the platform ends. I’m afraid I can’t find the photo in my cluttered attic. The image below is borrowed from an SNCF publicity poster. Amongst the line-up, I spotted a plaque awarded to the fastest train in the world. This must have been TGV set number 16 which established a world record on 26 February 1981 by achieving a speed of 380 km/h or 236 mph which is a bit faster than 100 yards per second.

Vue des annees 1980,

Patrick Janicek – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The next photo is one of mine and shows the unmistakable clock tower at Gare de Lyon. The 200ft high structure was built in 1900 for the Paris Exposition. Simultaneously, under the direction of architect Marius Toudoire the Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée (PLM) company terminus was extended to 13 platforms from the original 8 which had been completed under the direction of Francois-Alexis Cendrier in 1849. In the modern day there appear to be 12 platforms beneath the original train shed and another 10 (numbered 5 to 23, very French) under the giant glass roof of Hall 2. There are another four platforms underground.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Picture two shows a TGV set below the original pitched train shed roof. The service on the right looks like a sleeper as the consist appears to be a bit of a mixture. Sure enough, the carriage furthest to the right looks blue enough and, with the application of a magnifying glass, the crest partly cut off from the image looks grandiose enough for us to allocate it to the Companie International de Wagon Lits. To give the full title, the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (et des grands express européens). In English: The International Sleeping-Car (and European Great Expresses) Company.

Wagon Lit was founded in 1872 by yet another famous Belgian, Georges Nagelmackers, inspired by Pullman night trains during a visit to America. The company’s luxury trains were to include the Orient Express, the Golden Arrow, the Taurus Express and the Blue Train. That’s the inferior Calais Gare Maritime to Menton Train Bleu, not the superior Cape Town to Pretoria Blue Train proper. The height of Wagon Lit’s prowess came in 1931 when they operated 2,268 carriages providing services in Africa and Asia as well as across Europe. Nowadays the brand still exists as part of the Newrest group who provide catering and other customer services to train companies.

By the time your humble author was dispatched to Old ‘Stambul on the Orient Express it had been reduced to a disappointing single carriage on the end of a freight train. Rather than dowagers, diplomats or racy French divorcees, my fellow passengers included parrots, monkeys and barefoot Turks.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

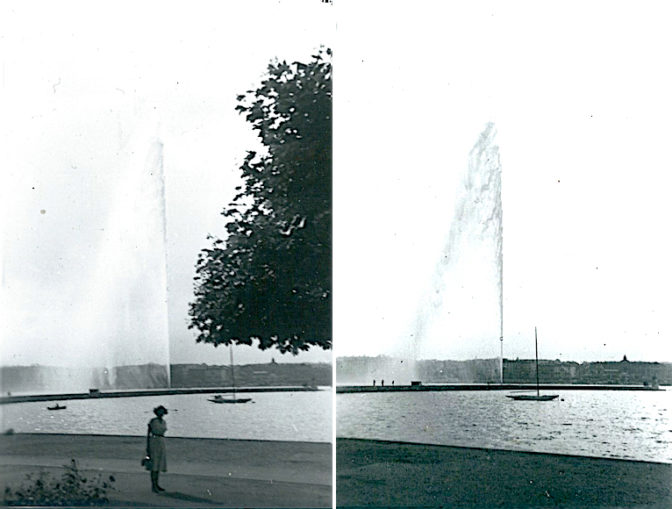

Three decades before that my grandparents were approaching Geneva by Ford Prefect. The first of their photographs shows my grandmother next to Lake Geneva’s iconic Jet D’eau. Situated where Lake Geneva exits at the river Rhône, according to wiki over 100 gallons of water per second are jetted to an altitude of 460 ft by two 500 kW pumps. The water leaves a 4-inch nozzle at a speed of 125 miles per hour. At any given moment, there are about 1,500 Imperial gallons of water in the air. The fountain can be reached via a stone jetty which is visible in the photograph.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

If we look above the pier to the right and fiddle with the contrast and brightness we can make out the outline of an interesting building on the other bank of the lake. A vague silhouette of a crown-topped cupola suggests this to be a former famous Geneva landmark, the Kursaal, a name often used in 19th-century Northern Europe, particularly for places of therapeutic pilgrimage. The word’s roots are German and mean ‘cure room’. One such cure being gambling.

The Geneva Kursaal, also known as the Grand-Cassino was built in 1884-85 by Francois Durel according to the plans of architect John Camoletti. Running along the Quai du Leman, now known as the Quai Mont-Blanc, the building brought together gaming rooms, a restaurant, a large terrace and a performance hall. The casino closed following the First War and was bought by the city of Geneva in 1921 to be used as a performance hall. Following a catastrophic 1951 fire at the Grand Théâtre de Genève operatic performances were held at the Kursaal. However, after the rebuilt opera was opened in 1962 the Kursaal fell into decline, had fallen into disuse by 1965 and was demolished in 1970. The unsightly gap on the Quai-front was subsequently filled by another interesting building that we shall take a look at next time.

Le Grand-Casino de Genève,

Walter Mittelholzer – Public domain

© Always Worth Saying 2023