Amongst a century of detritus at the BBC there lies some buried treasure. Between layers of fake news, preachy left-wing documentaries and un-funny comedy, the BBC’s iPlayer hides a gleaming gem of an old archaeology series. Each compact 30-minute episode follows the historical investigations, carried out both here and in distant parts of the Empire, of Sir Eric Robert Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD FRS FBA FSA.

Exterior of great enclosure, G.Zimbabwe,

Unknown photograopher – Public domain CC BY-SA 2.0

In Buried Treasure, one of the first-ever archaeological documentary programmes, Sir Mortimer Wheeler visited Southern Rhodesia and along with a Mr Roger Summers of the Southern Rhodesia Historial Monuments Commission, examined the stone ruins of the Great Zimbabwe National Monument, at one time thought to be the source of King Soloman’s gold.

To the accompaniment of African jungle drums Sir Mortimer, smoking a pipe and clad in safari jacket and baggy shorts atop high socks and sensible shoes, opened the programme by chasing a pair of shot-spoiling hippopotami while his voice-over told of “big game and endless bush.” “Every schoolboy knows his Africa,” he continued, “or thinks he does. A big, baked wilderness, then suddenly around a corner…” Around that sub-Saharan corner Sir Mortimer, complete with resplendent greying bouffant and magnificent handlebar moustache, happened upon one of the strangest ruins in the world; the ancient Great Zimbabwe archaeological remains after which the modern state that Southern Rhodesia became is called.

A mysterious name, Sir Mortimer speculated it might mean houses of stone. A reference to a stone-built enclosure atop a hill where centuries ago Arab traders bartered with African kings for the fabulous supplies of gold found in central Africa. Apparently King Solomon allowed a shipment every two years. The Queen of Sheba built stone houses there to hold the bounty while en route to the ports of the Red Sea.

All very romantic but not true, a rueful Sir Mortimer announced to his 1958 audience. East African Portuguese traders, both on the coast and as they headed inland, were the first to hear rumours of such a place. Driven on by curiosity and greed, the Portuguese left behind their own artefacts. Sir Mortimer displayed an antique cannon just about small enough and light enough to be handheld. And a gold medallion and an ivory figure of the Virgin discovered in a gold mine. During their exploration, the Portuguese literally put Zimbabwe, or Simbaoe as they preferred to spell it, on the white man’s earliest maps of Africa.

In 1890, three hundred years later, came the first permanent occupation by Europeans. A force of pioneers was sent northwards in oxen and carts from the Union of South Africa. Their wagons formed a circle at night to protect from attacks by the Matabele. Hauling through rivers, felling nearby timber to provide log-ways across swamp and river beds, their motto was ‘Peace with profit.’ Sir Mortimer narrated a damn good tale, illustrated with pictures of canvas-clad wagons, some of them upended by mishaps brought about by the unforgiving terrain or by native attacks. Having reached Salisbury, the hardy Saffas struck out for the ruins of Great Zimbabwe.

Curved passageways circling the Great Enclosure,

amanderson2 – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Ladies were present, including the indomitable Miss Alice Balfour, sister of Conservative prime minister A J Balfour. Her 1894 photographs of ruins, if not reclaimed by jungle then at least party encroached by bush, illustrated Sir Mortimer’s refreshingly crisp and informative script. Her images revealed a fortress of masonry and natural rock crowning a rocky hill.

Gold brought the Victorians to that part of Africa. The wonderfully named Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Company Limited (capital of £25,000 in 25,000 £1 shares, head office Bulawayo, Matabeleland) were responsible for the earliest excoriation of the area. There soon followed the earliest scientific excavation which, besides clearing the detritus of the ages, also began to clear away some of the romantic nonsense surrounding the site.

At this point, Mr Summers was introduced to viewers in oilcloth hat, spotless white starched shirt, Hitler moustache and horn-rimmed spectacles. Mr Summers, surrounded by theodolite, tape measure and pole, disappointed by informing us it was too early to give any definite results from his dig. However, sections excavated thus far showed that the walls were made in different periods and in different ways. He referred to one particular structure as a temple that had grown organically and hadn’t been planned in the way that one might plan a (bay-windowed, semi-detached Betjeman’s Metroland) house.

Even in those days there was such a thing as radiocarbon testing. Charcoal samples had been found and when they were ‘done’ there would be more to add to the story. Pegs and string were about the place. In the background, soil was being sieved by cheerful natives in baggy shorts. Sir Mortimer reminded us how little was known about the why, who and when. Imported artefacts helped with the when. Imported beads had crossed the Indian Ocean many centuries ago. Pieces of pottery from Persia had been found. Their decorative writing placed them in the 13th century. A porcelain bowl had travelled all the way from China in the 17th century.

Some of the oldest walls were supported by hardwood timbers. Radiocarbon showed it cut about 600 AD – an unhelpful conclusion for King Solomon and Queen of Sheba romantics. A steep climb approaches the fortress. Narrow passages and steep defences lead to a platform before thick high walls pierced only by a small doorway. This obviously looked like a high-place fort and sacred site guarding over a larger settlement on the flat land below. Stonework filled gaps in the natural rock. The remains of many generations of wooden huts formed detritus above the height of a man. Floors were made of ‘daga’ or dried clay. The curved lower walls of the circular huts were also made of daga and then topped by walls of mud and timber interspersed by regularly spaced wooden posts supporting a roof.

Nearby, Sir Mortimer was able to film natives in the then present-day trampling wet clay in a damp hollow. Once formed to the right consistency by barefoot men, the mud was carried away by women and applied to the timber walls of a hut. Things had changed very little since ancient times. Above the mud huts was the original Zimbabwe fortress. Vast gables of boulders were joined by alleyways and passages to form casements and passages. Sir Mortimer speculated it had been topped by a lookout post with beams or flags.

A space created by four such granite blocks was described by Sir Mortimer as a holy of holies where much gold had been found. Some of the precious metal went into the Ancient Ruins Company’s melting pot but some had survived and was kept safe in museum strongrooms. Likewise the pestles and mortars used to pound the gold-bearing rocks.

At the surface workings of a working gold mine nearby, still in bush gear, no need for a hard hat or hi-viz jacket, Sir Mortimer was pictured below an iron pounder grinding ore-bearing quartz. After the pounding, the reduced mineral was run over mercury where the liquid metal attracted the gold to create a half-mercury/half-gold sludge from which the precious metal could be separated after the sludge had been scraped up and processed. Any gold missed could be caught when washed over absorbent cloths. The ancients used sheep skins for the same purpose, hence the legend of the Golden Fleece.

Close to the modern processing plant was the original ancient shaft, now widened and still being worked. Historic tools had been recovered there. A hammerstone for reducing the quartz remained at the site. Other tools, such as the picks and bailers used underground, were also kept in the museum at Bulawayo.

Interior of great enclosure,G.Zimbabwe,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Back at the Zimbabwe acropolis, other treasures had been found. A soapstone bird, of unknown purpose, was described only as a ‘ritual object’. Another bird carved on a shaft above a climbing crocodile was almost as tall as Sir Mortimer. On the lower ground was another stone-built town, explored by an unnamed young lady. Stonework formed a protective wall enclosing wooden huts. A chap in plus fours and accompanied by a boisterous Setter, pointed to where stone abutments had existed between the huts. An illustration made sense of it, and suggested ancient life was lived out much the same as in an African village of the 1950s. To illustrate the point, the camera went to such a place and captured circular wooden huts with coned roofs of dry reed thatch. Chickens were about the dust. Native women dressed in light cotton dresses and head scarves pounded grain on the floor with tree branches. A hunting dog ambled by. In the background – the start of the bush. It all looked rather idyllic.

The wall carvings of the ancient Zimbabwe people were similar to those in the present-day village. They showed long-horned cattle, similar to those on nearby farms in that day. An old lady was pictured making a clay pot similar to those exhibited in the Bulawayo museum. An old African, as if from another age, sharpened an arrowhead on a rock. Likewise, gaming boards, little balls in grooves were used for a game similar to Chinese chequers. Locals took it turns to liberate Sir Mortimer from his gambled shilling pieces. A witch doctor plied his trade with dice and divining bones. Similarly decorated bones had been found on another ancient site near Bulawayo along with a witch doctor’s ceremonial iron axes. Decorative female figures pressed into the mud walls in the modern-day village were the same shape as statues from Great Zimbabwe. Long-legged and with prominent buttocks, breasts and navels they are thought to be religious or magical items connected to fertility.

The most famous structure in old Zimbabwe is the oval enclosure or temple. Judging it to Sir Mortimer, it stands a good 30ft high. The entrance is again narrow. Never having invented the wheel or axle and never having domesticated beasts of burden, the Africans had no need to build anything more than shoulder wide. The passageway accessed the remains of more huts. Thought to be a metalworking area, ingots of metal made from simple moulds had been found. Iron axes were made there too, and bronze razors and copper finger rings.

As well as metal workers, the inhabitants had been practical builders using blocks of granite without mortar. The ruins were located near naturally exposed granite that is often seemed or even laminated in horizontal layers. Fire can buckle the top layer and make it easy to detach.

To illustrate the point Sir Mortimer piled timber and straw above one such section of exposed rock and started a modest blaze. After two hours, Mr Summer was pictured, sans bush hat and with a glorious comb-over, clearing away the fire (while smoking a pipe) to reveal a layer of charred and split granite. Native children looked on, sensibly clad in sandals, shorts and shirts. A little girl wore a white dress and hat. Losing interest they tidied up behind themselves and hurried off to play.

With the help of native muscle power, buckets of water and a big stick, Mr Summers was able to produce a reasonable number of usable blocks in decent sizes. The stones were easily fitted into place by a trained builder at what looked like a well-organised effort to restore part of the site. The outer face was built up layer by layer, with the flattest side of each block being pointed outwards. Packing was placed behind the facing with, therefore, no need for mortar.

Mauch Ruinen,

Karl Mauch – Public domain

Back inside the oval enclosure, Sir Mortimer led the camera to a famous tower that sits at the end of a decorative approach of light and dark-coloured patterned masonry.

With nowhere else quite like it and with its purpose unknown, it was labelled as another ‘ritual object’. Small objects had been found there and kept in Bulawayo museum; such as carved lions like tiny bookends and flat beaten copper bells. Many of the walls and narrow passages thereabouts seemed to have no rhyme or reason other than it was possible to build them.

A smaller version of Great Zimbabwe, rarely visited, sits 70 miles from Bulawayo. The walls there are more decorative. Sir Mortimer left both sites impressed but confessed to being not much wiser. What could he tell us about them with certainty?

- They were built on rocky hilltops that dominated a wider landscape

- Were clearly defensive

- Constructed only on granite rock which is easy and plentiful building material

- In a zone of major rainfall beneficial to cattle and crops

- The residents of the actual fortresses were kings or chiefs, rich in objects and gold workings

- The gold trade dated back to the first Millenium AD when Arab and Indian traders voyaged to the east coast of Africa

- Some sites were still occupied as recently as 1700, as evidenced by the date of an unearthed Dutch bottle

What happened to those kings and chiefs and why they abandoned their fortifications remained a mystery. A mystery that Sir Mortimer concluded would keep his fellow archaeologists out of mischief for many years to come.

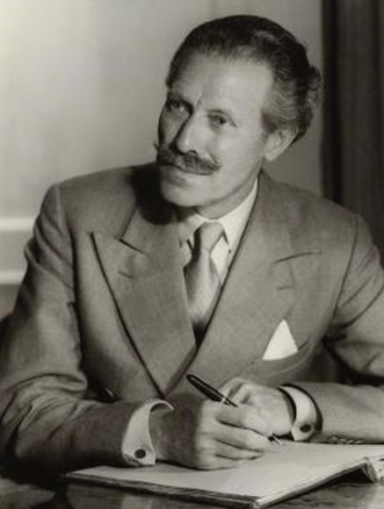

Photo of archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, 1956,

Howard Coaster – Fair use: Provides identification, no alternative, low resolution

© Always Worth Saying 2023