Royal Engineers No 1 Printing Company., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

My paternal grandfather, Herbert, was born in Morley in 1875 to a family of coal miners and woollen weavers. The sixth of twelve children, he was a master boot and shoe maker and repairer. As an integral part of researching my paternal grandparents, I looked at his army service during WWI. I knew he had been a soldier because I had a photograph and a medal, but, although I had seen him regularly for the first eight years of my life, I never really knew him or anything about his life.

Those of you who have tried to research relatives’ WWI service will know how difficult it is, primarily because so many records were destroyed in 1940 during WWII German bombings.

The only full set of WWI data are the Medal Rolls Index cards, which were not destroyed during WWII, and are probably the best place to start if you don’t have full regimental details. Although the National Archives can provide the information free, my own research suggests that they are not always helpful (even with full details, I have only just found my grandfather’s records there via a link from another site!). You may well need ‘Find My Past’, where records can be purchased on an individual basis. This is where I originally found my grandfather’s service records: my only problem was deciphering the 100+ year writing, abbreviations and hieroglyphics!

From my perception of him, (or perhaps my mother’s), I would have guessed that my grandfather would have been a “reluctant soldier”. Always truculent in the face of authority, I reasoned that it must have irked him in the extreme when he was called up in 1915, at the age of almost 40 (the maximum age at the time was 41). However, I was amazed to find that he had, in fact, volunteered, just 12 days after his marriage to my grandmother on 17th July, when he joined the Kings Own Royal Lancaster Regiment on 31st July 1915, and was posted to the 11th Division.

My next surprise was to find how small he was (to young children all adults are ‘big’): just 5’ 2”, he weighed 9st 5 lb, with a fully expanded 36” chest: his physical development was shown as “Fair” and, unsurprisingly, given his trade, he had perfect sight in both eyes. At least, now I know why I am smaller than everyone else in my family!

I might have asked myself how someone so small could enlist as a soldier, and, if I had the knowledge I have now, I could have answered the question. It was while examining the books available from the Kings Own Royal Lancaster Regiment Museum that I had my ‘eureka’ moment, which explained why a pint-sized Yorkshireman would have travelled to Blackpool to join a Lancashire Regiment, when I discovered a book by Major Carter, entitled “Bantams at War”, a history of the Kings Own Royal Lancaster 11th Brigade.

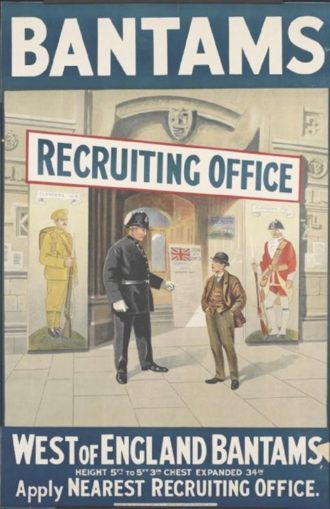

Unknown (artist); Partridge and Love Ltd, Bristol (printer); 35th (Bantam) Division (publisher/sponsor); Recruiting Committee of the Mayor’s Committee on National Defence (publisher/sponsor), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bantam Battalions

I had never before heard of Bantam Battalions in WWI, and those of you who are equally ignorant, might be interested to know the history.

When WWI was declared, the minimum height for a soldier was 5’ 3”, and shorter men were refused enlistment. Tradition has it that a determined unnamed 5’ 2” Durham miner walked between all the Recruitment centres and was refused by them all. At the last one, Birkenhead, he offered to fight anyone who said he was too short for a soldier, and it took six men to restrain him. His MP, Arthur Bigland, took up his cause and, eventually, Bantam Battalions were established, which exclusively recruited healthy men who were a minimum of 5’ and less than 5’ 3” tall. There were other stipulations, such as a minimum 34” chest, but the key innovation was that all the short men fought together – a Lilliputian army, if you will. By the end of the war, there were 29 Bantam Battalions with around 30,000 men.

The initial Bantam Battalions recruited mainly miners, who were, by dint of their trade, small and hardy. Their size did give them certain advantages in the trenches (they could not be seen, for example) and ideally suited them to construct tunnels.

As time went on, it became increasingly difficult to replace injured and killed Bantams with small, healthy men, and unscrupulous recruiters used these battalions to recruit weak and/or underage men, whose lack of fighting prowess damaged the reputation of the Bantams.

Eventually, the Bantam Battalion experiment was abandoned, never to be repeated, and today the minimum height for a soldier is 5’.

Herbert’s WWI Service

© Chrissie 2022

Back to Major Carter’s “Bantams at War” – not the best read I’ve ever had – definitely, a book for soldiers written by a soldier, all facts and no feelings. Nevertheless, thanks to this slim 23 page booklet, and the information gleaned from the Kings Own Museum, I now know exactly what my grandfather was doing for every day of his war service for the two years between July 1915 and July 1917.

Immediately following enlistment, the Battalion was quartered at Bowerham Barracks, Lancashire and, in early October it was moved to Aldershot and subsequently to Blackdown, near Farnborough, where training was completed.

It is here on 18th February1916 that we find Herbert up on a charge of “Interfering with a Policeman’s Duties”, which led to his being confined to barracks for ten days. I gather this indicates that it was not a very serious misdemeanour.

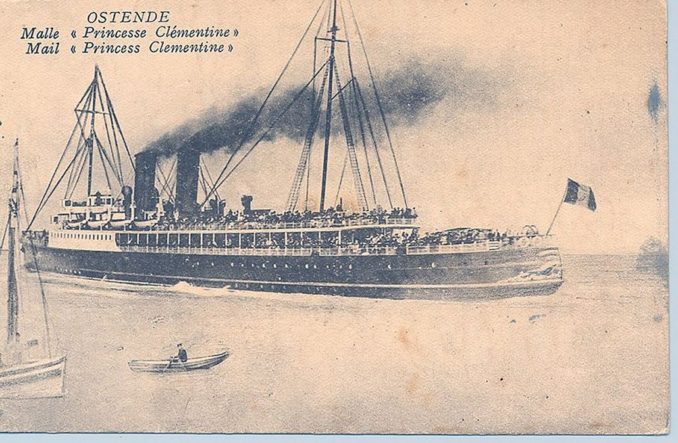

Not used to lack of activity, I assume Herbert was bored. This was to change on 2nd June 1916, when the Battalion took two trains from Frimley to Southampton. In total there were 34 officers, 994 other ranks, 32 animals and 21 vehicles. In Southampton, the troops boarded the SS Clementine for Le Havre, arriving there the following morning (Note: I think this should read “Princesse Clementine, a Belgian paddle steamer, loaned to the British Government in 1915, which spent the war transporting troops between Folkestone and Southampton and France.)

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Once in France, the Battalion proceeded by train and on foot to Béthune, Battalion Headquarters, (18 miles north of Arras), where it arrived on 12th June. The first casualty occurred en route on 4th June, when a man cut his hand while opening a tin, and, despite being hospitalised, poisoning set in, and he died.

At Béthune, my grandfather’s Division (B) was attached to 8th Battalion Seaforths, training in trench warfare took place, and steel helmets were issued, which, as Major Carter pointed out, “proved very useful not only for defence against shell fire, but as a protection to one’s head when entering dug-outs with very low entrances”. Quite.

So that I do not try the patience of expert readers, I shall cover only the first six months of Herbert’s stay in France, to give non-experts a flavour of what life was like for this, and other, British WWI soldiers.

On 11th July 2016, the Battalion moved up into the line for the first time as a Unit, taking over a section of the Maroc Front (9 miles SE of Béthune). Included in this Section was the Double Crassier, (a slag heap writ large), three quarters of the length of which was held by the Germans. The Battalion was relieved on 15th July, and went into Brigade Reserve. Eight officers, who had been left behind in England, re-joined the Unit on 20th July. The Battalion moved into the Calonne Section (6 miles SW of Béthune) for its second tour of front line duty, where it remained until the end of July.

After a two-week deployment to the Loos Section, and subsequent relief, the Battalion carried out two consecutive tours of the Calonne Section, where it was primarily involved in tunnelling. On the night of 24/25th August, six reconnoitring patrols were sent into “No Man’s Land”, and found enemy working parties repairing and putting out new wire, who were promptly dispersed by Lewis Gun fire. On 29th August, a number of non-explosive Rifle Grenades were fired, with messages attached notifying the proclamations of War issued by Romania and Italy.

After Brigade Reserve, on 12th September, the Battalion went to the line in the Maroc Section, (9 miles SE of Béthune),and, on the 19th carried out a raid on the southern side of The Triangle (trench), with the aim of identifying the enemy holding the position and inflicting damage on him and his trenches. No Germans were found.

A similarly futile raid was carried out in late September 1916, when the Battalion was on front line duty in No. 14 Section. A raiding party established the best place to place a torpedo, which was fired. When the raiding party entered the Sap (short trench in No Man’s Land), it was found to be empty. A further tour of duty was carried out in the same Section from 4-8th October, and again on 12th October, when the Battalion took over the right subsection of the Hullock Section (near Loos), an area renowned for mining and counter-mining activities and for the attention paid to it by the enemy Heavy Trench Mortars.

On the night of 13-14th October, a successful raid was carried out, for which Temporary Second Lieutenant, L N Cook, was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry, having personally killed four Germans when he found himself alone with them in a trench, incurring slight wounds to his head and knee.

Thomas Keith Aitken (Second Lieutenant), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During its first three months in France, the Battalion had operated around the Bethune Divisional Headquarters. On 27th October, the Battalion started its march east to Arras, and finally arrived in Prouville on 4th November, where it rested until 11th November, receiving Winter Clothing and carrying out attacking training: movement in artillery formation was particularly practised.

Between 12th and 21st November, the Battalion occupied the line east of Hébuterne (15 miles SW of Arras), which was an area of fierce fighting throughout WWI, with the German Imperial

Army stationed only 800 yards away in Gommecourt. The weather was extremely cold, and the Battalion and the village were constantly shelled with heavy guns.

On 23rd November 1916, the Battalion started its march to new billets in Bussus (9 miles E of Abbeville), where it carried out training and improving of the billets, including the erection of wash places.

On 12th December, the Battalion marched to a new camp 1 mile north of Chipilly (17 miles east of Amiens), where it remained until the 24th. Because of the very muddy state of the camp, little training was done, and the Battalion was confined to camp throughout its time there.

On 31st December the Battalion went into camp north of Suzanne (19 miles east of Amiens) and New Year 1917 saw it in the front line on the Rancourt Section (30 miles north east of Amiens) where it remained until 8th January. During its time there it was heavily shelled, and, as the trench line was not continuous, it was necessary to patrol frequently. Rain fell heavily and much time was spent in trying to make dry standings for the men in the Line.

After a period in Division Reserve, it returned to the Line on 19th January in the Bouchavesnes Sector (1 mile from Rancourt),and was relieved on 23rd January. During this tour, the Line was subject to constant gas shelling. A telling comment was made by Major Carter, “No casualties were suffered during this tour – the first time since they had commenced active service that they had been so fortunate.” The Battalion had been in France for six months.

And here I will stop the detailed description of Herbert’s war, so that I do not test my readers’ boredom thresholds too far.

Herbert was transferred to 237 Divisional Employment Company (part of the Labour Corps) on 8th June 1917 and to 226 Divisional Employment Company on 14th August 1918. The Labour Corps consisted of men who were no longer considered fit to fight on the Front Line: they were often despised, but their work was essential to supply the men on the Line, and they were never far away from enemy action, although they themselves were not allowed to bear arms. Unfortunately, no Company War Diaries were required to be kept, so that details of their service are largely lost.

As a member of the Divisional Employment Company, Herbert would have stayed with the Division attached to Divisional Headquarters, but working six days a week without relief: he would have been deployed wherever he was needed. I am hopeful that he was lucky enough to resume his boot repairing trade.

The Battalion went on to serve at Passchendaele (July–November 1917) and Cambrai (November-December 1917) and was disbanded on 17th February 1918, but Herbert remained abroad, and was demobilised a year later on 29th January 1919.

In his “Statement as to Disability”, it shows that he has served 2 years 8 months in France, Belgium and Germany. Because of this service, according to his deposition, he is now suffering from “Rheumatism, starting December 1916, and Shattered Nerves, starting June 1917, both caused through exposure.”

The Examining Medical Officer, who assessed his disability claims the day after his return to the UK, ruled that he had signs of neither disability.

WWI Medals

Establishing the medals my grandfather was awarded in WWI proved onerous, as his so-called ‘Medal Card’ was simply stamped ‘medal’. I was eventually able to obtain a definitive answer from “Military Genealogy”, a site I had never previously heard of. It confirmed what I had surmised he should have been awarded:-

The British War Medal

The Victory Medal

And here is the one I have:-

© Chrissie 2022.

Herbert in the Second Boer War

Herbert’s “Statement as to Disability” on his demobilisation suggests that he first enrolled in the army in Leeds in April 1898, and served from 1898 to 1902. It cost me a great deal of time in attempting to find this earlier service, and for weeks I could find no mention of it, although I realised that Herbert’s age (he would have been 22) would have made it possible.

I must confess that I did wonder if he had invented it, but, by now, I should have known better than to doubt him. I eventually found his enlistment in 1898 to the York and Lancashire Regiment in the ‘British Militia Attestations Index’. He had falsified his year of birth to suggest he was three years younger than he was, no doubt, once more, trying to get round his height problem.

Thanks to some kind friends on a military blog, I discovered that my grandfather had, in 1903, been awarded the Queens South Africa Medal with Cape Colony Clasp and 1902 clasp. Regrettably, I have no idea where Herbert’s medal went. The Cape Colony Clasp is, unfortunately, unhelpful, in identifying exactly where he served, (the Boer War medal equivalent of ‘not elsewhere specified’), but, having just received the only book on the Regiment’s service in South Africa, this may well be the subject of a future article.

Epilogue

When I embarked on research into my grandfather’s military service, I had no idea what to expect. If anything, I thought he might have been somewhat resentful of being conscripted at the age of almost forty. Instead, I found that he had volunteered, and not for the first time.

Whatever I had expected, I found a pint-sized patriot, eager to “do his bit” for his country.

R.I.P. Grandad Herbert, I wish I had known you better all those years ago: I can now see that you are a grandfather of whom I can be so very, very proud.

© Chrissie 2022