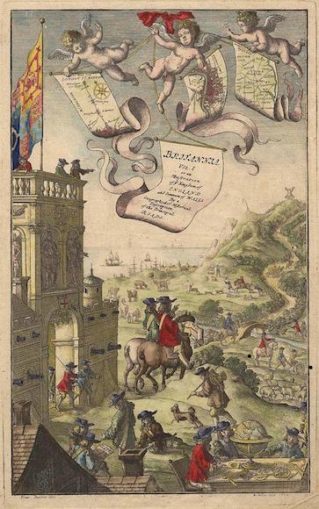

Frontispiece from Volume 1 of John Ogilby’s Britannia 1675, drawn by Francis Barlow, engraved by Wenzel Hollar,

Licence Public domain

Introduction

Sorry to disappoint you so early in the piece, but this article is not about the antics of the young Tom Jones, although undoubtedly he and his dissolute friends could and should have availed themselves of the “strip” maps, which are the subject of this paper.

Imagine the young Tom Jones, banished by Squire Allworthy, and needing to make his way from Somerset to London. If he’d had the appropriate strip maps, he might have improved on his circuitous journey to London via Gloucester, a stay in Upton on Severn, and, finally, Daventry!

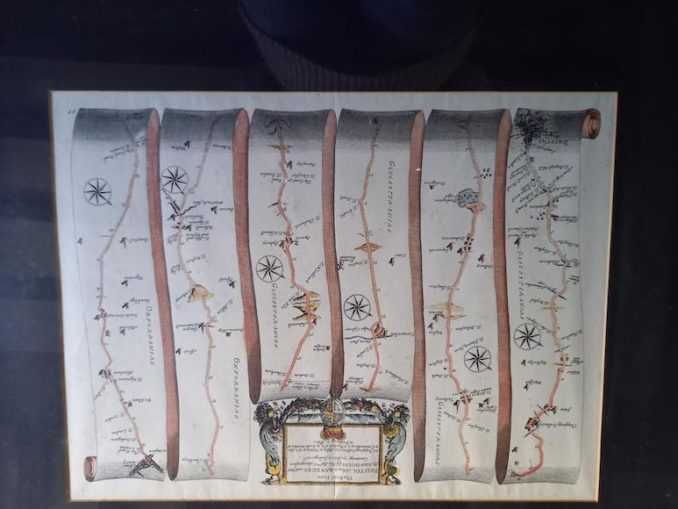

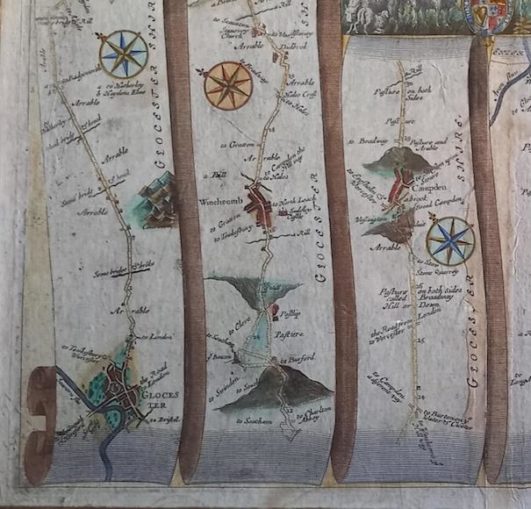

Before discussing the detail of these maps, I would like to look briefly at the conditions which faced the long-distance traveller in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the meantime, for anyone who is not familiar with strip maps, here is an example of the way they looked.

© Chrissie, Going Postal 2021

This shows the route from Bristol to Banbury, complete with topographical details and cumulative mileage. The map is read vertically from the bottom of each scroll to the top, starting on the bottom left of the map and ending on the top right.

Road Travel

The Romans had left an excellent network of roads throughout England and Wales. However, following their departure in the 5th century, their roads fell into disrepair, largely through the superstition that they were built by giants, and the limited need for travel prior to the Norman Conquest, when our isles were divided into a number of separate kingdoms.

Nevertheless, they remained some of the best roads in the land, albeit that their condition made travelling by horse or horse and cart lengthy and laborious.

“Flying” Coaches

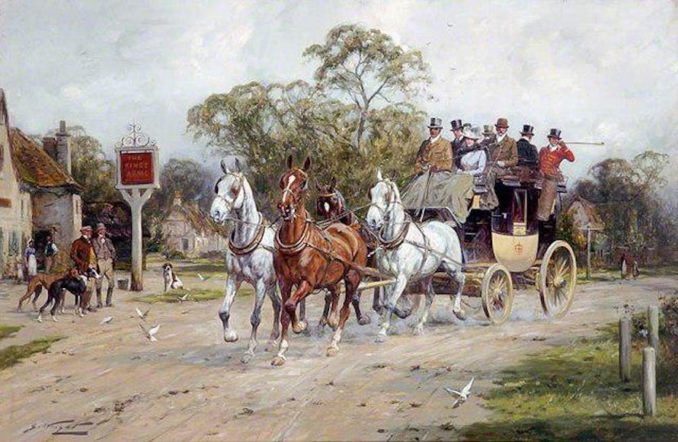

The first horse-drawn coach to carry people is recorded in 1555, but travel was still extremely slow and uncomfortable. Progressively, roads and coach design improved so that, by 1749, when Tom Jones was published, a network of “flying coaches” had been established in the UK, i.e. scheduled services between major towns.

A coach passing the King’s Arms ,

George Wright – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The stagecoach, so-called because it travelled in “stages” (the distance a team of horses could travel without being changed), was generally pulled by four horses, sometimes six, and officially held four passengers inside and six on top (although bribery of coachmen for scarce places often led to dangerous overloading), and normally covered 60 – 70 miles a day. The fare per passenger was 1/- per five miles (approximately £12 today). It is worth noting that 1/- was a typical day’s wage for a labourer, and could, equally, buy you 6 gallons of beer or 4lbs of meat.

Toll Roads

Progressively, roads fell under the control of local trusts, not for profit organisations, run by local worthies, whose remit was to plough back tolls collected into maintaining or improving the roads under their control. The distance covered by a trust could be as little as 20 miles, although it could be a much as 100 miles.

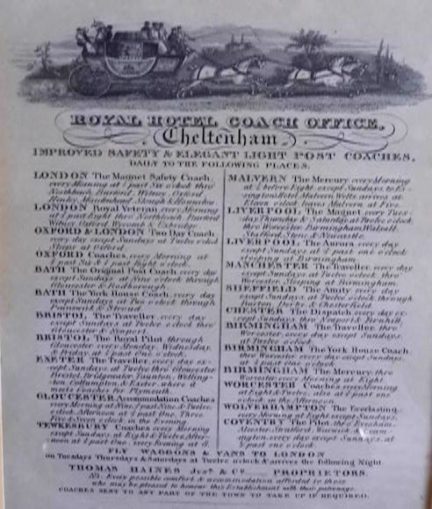

© Chrissie, Going Postal 2021

The maximum charge for a 4-horse stagecoach was 1/6 (£18). It is estimated that, by the end of the eighteenth century, around a quarter of all roads in England and Wales were run by trusts. See above Cheltenham coach routes.

Turnpike Houses

Tolls were collected at turnpike houses or booths. The name “turnpike” is taken from a defensive spiked roller, which was used to stop cavalry charges, similar in purpose to today’s police stingers, and is, of course, a term still in use in modern America. Roads were closed off via gates, which horsemen and farmers with flocks tried to evade bypassing via the fields.

The Roound House at Stanton Drew,

Rodw – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Coaching Inns

A team of horses could be changed quite quickly, and coaching inns kept replacement teams, as well as refreshments for the weary travellers and overnight rooms where required. Many of the “olde worlde” village inns we know and love today opened at this time. Inns were originally 7 miles apart, but soon accumulated at popular stopping points, where competition became fierce.

The White Lion Inn at Upton on Severn (where Tom Jones purportedly disported himself).

The White Lion Hotel, Upton upon Severn,

Ronaldoo – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

John Ogilby

Until 1675, there was no road atlas anywhere in the world, and it fell to a British man in the twilight of his life to produce the very first one.

The life of John Ogilby should be viewed against the tumultuous times in which he lived. He was born in 1640, shortly before the ascension of James VI of Scotland to the throne of England and Scotland (as James I), on the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. Upon James’ death, he was succeeded by his son, Charles I, who rapidly quarrelled with the English and Scottish Parliaments. This led to the English Civil Wars (1642 – 1648), as a result of which Charles was executed in 1649, and Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector from 1653 until his death in 1658, when his son, Richard, briefly took over. In 1660, the monarchy was restored with the accession of Charles II to the throne.

Portrait of John Ogilby, after Sir Peter Lely, oil on canvas, 1662,

Peter Lely – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

John Ogilby was no ordinary man (for a start, he kept his head when all around him were losing theirs!). He was a serial adventurer, impresario and entrepreneur, who no sooner made a fortune than lost it, only to bounce back again with a new project. The son of a tailor, born into a good family north of Dundee in 1600, he went to London as a young child with his father, who followed the Scottish Court there in 1603. His father was a member of The Merchant Taylors’ Guild, and John almost certainly went to the Merchant Taylors’ School.

Unfortunately, Scots were not popular in England at the time, and his father’s business failed. John was forced to abandon his studies at the age of 11, when it fell to him to support himself and his mother after his father was thrown into a debtors’ prison. It is probable that he existed by selling his father’s extensive stock, which, as was often the case, had not been declared to his creditors.

Fortuitously, or so the story goes, he had a small lottery win, and was able to buy his father out of prison and purchase himself a dancing apprenticeship in London, subsequently setting up his own dancing school. For reasons I have difficulty in understanding, dancing was a requisite of budding lawyers at the Inns of Court (apparently, celestial harmony governed their interpretation of the law). Unfortunately, during a masque before the Duke of Buckingham (Charles I’s “favourite”), John fell, and was lame for the rest of his life.

He then seems to have become an upmarket mercenary in Europe, in support of the Stuart emigres. He was isolated from his comrades, and, amongst other achievements, he became the captain of a ship.

We next see him in Ireland, where he set up the first theatre, and was appointed Master of the Revels of Ireland, until the Irish Rebellion, in 1641, necessitated the closure of the theatre. In 1644, he left Ireland, was shipwrecked, and arrived back in England penniless.

He spent the next four years in Cambridge, where he worked with a friend on translations into English of the Bible and the classics of Virgil, Homer and Aesop, before returning to London.

At the age of 50, with demand for masques and theatres gone in the new Puritan era, he decided to marry and carefully chose a widow, Christian Hunsdon (17 years his senior) with a grown-up daughter and a grandson, William Morgan, who would become John’s business partner and heir.

He opened a publishing house and plagiarised the works of others to produce beautifully illustrated maps of faraway places, such as Africa, America and China.

Following the Restoration of Charles II, Ogilby was given a commission to compose speeches and songs for the coronation in 1660. Following another brief sojourn in Ireland, Ogilby continued his printing career back in London.

In 1660, disaster struck with the Fire of London destroying Ogilby’s printing works as well as all his stock. Always one to turn a disaster into an opportunity, he got himself and William appointed as official surveyors of the City of London.

Britannia

It was at this point, in his early 70s, that Ogilby embarked on his most ambitious project to date – to map all the principal roads of England and Wales (Scotland was never considered), under the auspices of the Royal Society and the patronage of the King, and, in 1674, he was appointed “His Majesty’s Cosmographer and Geographick Printer”, with a stipend of £13-6-8 a year.

Until this time, long-distance travellers had the choice of using lists of the towns on a desired journey (without directions) or employing a guide.

Ogilby’s methodology was to send surveyors on horseback along the various roads, with a measuring device which he invented, a rolling wheel with a handle which he called a “way-wiser” (no doubt pushed by more lowly beings) and check their work on their return.

Frontispiece from Volume 1 of John Ogilby’s Britannia 1675, drawn by Francis Barlow, engraved by Wenzel Hollar,

Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The two way-winder operatives are supervised by a surveyor on horseback. (See also the two surveyors with a map on horseback in the centre of the extract.)

Their findings were translated into strip maps based on 1 inch to the statutory mile. Today we would take it for granted that measurements would be in statutory miles, but, in 17th-century England, distance was also measured in local miles which varied enormously in length (hence, the expression “a country mile”), which could be up to twice as long as a statutory mile. Modern checks have found that the measurements were accurate.

In passing, it is worth noting that the word “road” had only recently been coined in place of the previous “highway”.

The following is a section from Ogilby’s map from Gloucester to Coventry.

© Chrissie, Going Postal 2021

Notice the depiction of Cleeve Hill (bottom second scroll from left) and Fish Hill (Broadway), near the bottom of the third scroll from the left. These both illustrate how steep hills were portrayed – upright to convey an incline and upside down to represent the descent.

The maps, all in black and white (any colouring is later), accompanied by details of the main centres of population and country homes on the individual maps were bound into a large volume. There were 100 maps and the volume weighed no less than 18 lb. It was not something that could be used by a horseman or a coachman, even supposing they could read. It has been suggested that individual pages were torn out to use, but, given the price of Britannia, this seems highly unlikely.

It is clear that this was never considered for mass production: the subscription price of £34 (£4,000 in today’s values) ruled that out. The price was equivalent to a year’s wages for a skilled tradesman, and could have alternatively bought you 6 horses or 8 cows.

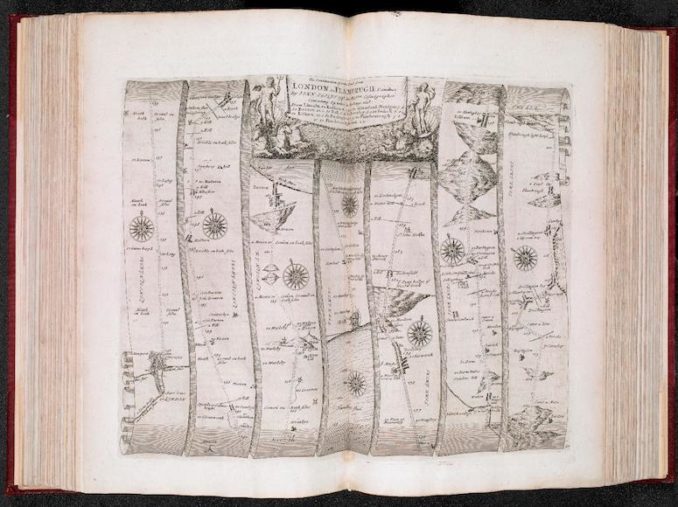

Britannia, volume the first,

John Ogilby – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

It seems to me that Ogilby’s other publications give us the clue to this. All had been beautifully presented with impeccable illustrations – with high prices to match.

I believe that Britannia was the seventeenth-century equivalent of a coffee table book, most probably with pride of place in a library, in line with all Ogilby’s previous publications.

Whatever they were, they were not popular enough to generate the subscriptions to cover the costs, and Britannia was published in a hurry in 1675, when, according to William Morgan, after Ogilby’s death, only £900 subscriptions had been pledged, compared with £7000 costs (a deficit approaching £1.5 million at today’s prices). Unsurprisingly, the original scope of Britannia had been somewhat curtailed, so that against the 40,000 miles promised, only 7,500 miles were actually covered, and Volume 1 became the totality.

John Ogilby died the year after its publication, in 1676, and was survived by his widow, who died the following year.

Relevance of Ogilby

If Britannia had stopped there with the death of its author, it would have remained no more than a curiosity in the history of map-making. Ogilby was a 17th-century man creating 17th-century products for a small, privileged market. However, if Ogilby failed to see the modern commercial potential of his strip maps, others were not so blinkered.

With copyright restricted to 14 years for a dead author, numerous strip road volumes, plagiarizing Ogilby’s work, were produced. The most successful of these was the result of cooperation between John Owen and Emanuel Bowen, first published in 1720 and republished multiple times until 1764. Britannia Depicta or Ogilby Improv’d, Being a Correct Copy of Mr Ogilby’s Actual Survey of All Ye Direct and Principal Cross Roads in England and Wales: Wherein are Exactly Delineated and Engraven all Ye Cities, Towns, Villages, Churches and Seats and Situate in or near the Roads with their Respective Distances in Measured and Computed Miles. Talk about rubbing salt in the wound!

This strip atlas was pocket (or saddle-bag) sized with 273 double-sided maps, and, as such, was eminently practical for a horse rider or coachman. Ogilby’s model remained the blueprint for road atlases until well into the 19th century.

In the example shown below, from Britannia Depicta, the road from Worcester to Bromyard, the route seems to have been largely determined by the availability of the stone bridge at Pershore, the only permanent crossing of the River Avon in the area (clearly restored since its destruction in the Civil War), illustrating vividly the limitations of road travel in the eighteenth century.

© Chrissie, Going Postal 2021

Epilogue – Was it part of a Papist Plot?

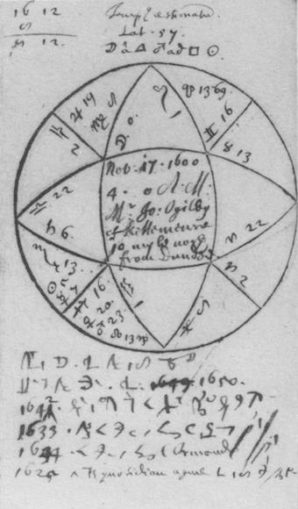

In 2016, Alan Ereira, wrote a book, The Nine Lives of John Ogilby, (based on a BBC Wales programme, presented by Terry Jones) which purported to show that Britannia was part of a papist plot instigated by Charles II to restore divine right to the monarchy and Catholicism to the country with the help of the French. It drew on the horoscope shown below.

Horoscope of John Ogilby taken by Elias Ashmole,

Elias Ashmole – Licence Public domain

It was purported that Britannia was compiled to guide French forces when they invaded England in support of Charles II, who was desperate to throw off the yoke of Parliament and achieve his dual goals.

That Charles should hatch such a plot does not surprise me in the slightest: the Tudor and Stuart periods were characterised by Protestant and Catholic plots, and spies lurked behind every arras. However, I find it inconceivable that a man, albeit a Royalist all his life, who had survived all the changing governments he had seen by adapting to new circumstances, would have risked everything on Charles’ coup.

As evidence, the book cites the rushed completion of Britannia, the severe curtailing of its scope and the errors in it. It also highlights the omission of several large cities, such as Liverpool, and the inclusion of minor (at the time) ones, such as Aberystwyth. Against that is the fact that Britannia was cumbersome and not at all suitable for use by a moving army and Ogilby was an old man, not in the best of health, and seriously short of money.

At the very least, if the maps were so important to the plot, the Royalists would have ensured that Ogilby had the funds to complete Britannia, whereas, as we have already seen, he was seriously short of money and Britannia was a pale imitation of the original concept.

I must declare upfront that I only skim read this 300-page tome, and I fully accept that I may have missed one or two nuggets which might have changed my mind.

In the final analysis, however, I have to admit that my rejection of the theory is buoyed by two of my own prejudices. The first of these is that it was largely based on a horoscope, something which I regard as “mumbo jumbo”.

From this horoscope, Ereira claims to deduce that Ogilby was the son of a Scottish clan leader, Lord Ogilvie, First Earl of Airlie. Unbelievably, the child was conceived when his father was away, was given the same Christian name as one of his other sons, (still alive), and was given away at birth to Ogilby the tailor and his wife. The theory goes that it is because of his noble birth that he is watched over all his life, (by other high-borns, presumably) and rescued by them from his various escapades.

And the other reason for my scepticism? Ereira was a BBC producer for thirty years. I rest my case.

© Text and Illustrations (except where specified otherwise) Chrissie 2021