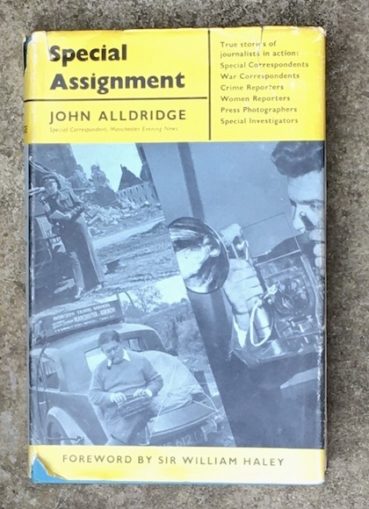

Another chapter from “Special Assignment” by my uncle John Alldridge

(published in 1960 and now long out of print)

No copyright claimed,

No Half-Way For Ladies

When I got my first job on a newspaper twenty-five years ago it was still very much a man’s world.

My old editor wouldn’t have a woman on the staff. “This is a tough life,” he would give as an excuse. “A woman would never stand up to the strain.”

And when he retired and the first woman reporter made her shy appearance she got the only jobs considered fit for a woman: covering church bazaars, reviewing books, writing snappy paragraphs about the latest hat and the price of fish.

But that was all in the Dark Ages before World War II. Nowadays the woman reporter goes pretty well everywhere and does pretty well everything. She may start her day interviewing a bishop at breakfast, and finish it consoling a broken-hearted film-star. About the only things she hasn’t done is report the Cup Final or cover a Test Match.

And that’s not quite fair, either. For the best Sports Editor I’ve ever met was a woman.

Of course there will always be stories that men can do better than women: I doubt very much whether a woman reporter could have followed Ralph Izzard to the foot of Everest; or have driven her way, wounded, out of a civil war, as Noel Barber had to do in Hungary.

But in her own field – the ‘human interest’ story – the woman reporter is unbeatable. Because she is a woman she is blessed with that light touch which, in these days of big circulations, can sell almost as many copies as the Saturday football special.

Few women reporters I know have a lighter touch than Nesta Roberts, of The Guardian. For years her gift of seeing the funny side of a dull story has made her irresistible reading.

When Nesta Roberts was at school – a very traditional girls’ boarding school – they said: “Journalism is so precarious, dear. If you don’t want to go on with your music, why don’t you go to the university to read English?” She meant to, as a preparation for being a famous novelist; but somehow she went instead, a few months before her eighteenth birthday, into the reporters’ room of the Barry and District News, one of the two weeklies in her home town.

There were four other reporters, all boys, aged from sixteen to nineteen. She started at nothing a week and after four years was getting ten shillings. She had also learned verbatim shorthand and eaten more wedding cake than anybody of her age, weight, and size in Britain because ‘the Girl always does weddings’. There was a feeling, too, that ‘the Girl’ should do plays, concerts and exhibitions; not because she might be good at them, but because she couldn’t get into trouble at that kind of engagement. On the whole she was rather more proud of graduating to covering the police court and the monthly council meetings than she was of having sold her first two backpagers to the Manchester Guardian, which she did during her second year on the weekly.

The next move was to a country weekly, The Louth and North Lincolnshire Advertiser. Here it was courts and council meetings again, all the ‘culture’ there was, and most summer Saturdays spent covering village fêtes with baby shows and bowling for pigs.

The staff was so small that nobody worried much about her being a woman. When a job cropped up they simply asked: “Is her shorthand up to it?”, and, since it was, she wrote ‘specials’ and feature-articles, and was saddled with a weekly gossip column called “The Musings of Miranda”.

She stayed there fifteen months before moving to what she still thinks of as the best evening paper in England, the Grimsby Evening Telegraph. There had been two women reporters there before her, and there was not a shadow of anti-feminine prejudice, though this was before the war. The four men reporters welcomed her as an equal, the news editor accepted all the ‘specials’ she produced, gave her ideas for others and put her name large above them. There was a weekly women’s feature to write, there was a children’s corner, and, every day, there was a fair whack of the ‘diary’ jobs. When the chief sub wanted a day off she wrote the ‘leader’, and she has always lacked a proper respect for leader writers since then, because the ones she wrote without knowing anything about anything were exactly like the ones the chief sub wrote. In the same way, on her first weekly, she twice wrote the sports column when the regular man was off.

She stayed four years in Grimsby and left it regretfully for the Nottingham Journal and Evening News. This was the mixture as before, with a good deal more ‘culture’ and with the pleasant experience of having two women colleagues instead of one or none. The other two were first class general reporters and the way the trio got on disproved all the myths about women quarrelling.

She had twice applied for a job on The Guardian before; in 1947, The Guardian wrote offering her a job. The moral of this is, she says, that applications really are filed for reference. She was the first woman to work in its Manchester office but has since had at different times three women colleagues and looks forward to having others.

She has done virtually everything in the book – election surveys, a dock strike in Dublin, the T.U.C. and Labour Party Conferences, descriptives, interviews, leader page articles, and thinks of herself simply as ‘a reporter’ not ‘a woman reporter’. She would like to think that her colleagues think the same – on duty. But she had developed a passionate interest in certain subjects, like social welfare, which are always looked on as ‘women’s interest’; and she accepts that part of the duty of a woman reporter is to be ready to tell all her men colleagues what the Queen really is wearing on Press visits; and to be ready to supply aspirins and sew on buttons in the office; also to give advice about birthday and Christmas presents for wives. She isn’t a famous novelist yet. . . .

The only moral she can find in all this is that “a reporter is a reporter is a reporter” as Gertrude Stein would say; and if a man reporter is going to be bad at the job he will be just as bad as she would be. There are a very few jobs on which no news editor would send a woman if a man was available. But for most jobs a news editor just looks for a competent reporter.

As Nesta says, she has done every job in the book. And one or two that were never in the book. She once set out for North Wales to a Headmistresses’ Conference at Bangor; and instead found herself half way up Snowdon on a wet Sunday morning looking for a couple of climbers who had got into difficulties. What was more, she found them: and filed a front-page story an hour ahead of the first man on the spot.

However the story I’ve asked her to tell has nothing to do with mountain rescues. It is one of those gay, off-beat, slightly pixylated assignments that happen once or twice in every reporter’s life and that he never quite forgets.

But let Nesta tell it in her own inimitable way. She calls it:

Fairies at The Bottom of The Garden

When I was a small girl my grandmother in North Wales once told me that when she was a small girl her grandmother told her that she had looked out of her bedroom window in the middle of the night and seen the fairies dancing in a ring in the garden.

I didn’t believe in fairies myself – at least, I didn’t think I did – and so far as I knew my grandmother didn’t either. But she quite clearly believed in her grandmother’s fairies. I never understood how you could believe and not believe like that until I met Mrs. Esterhazy. Well, actually, her name wasn’t Mrs. Esterhazy, but it was one of those names that are a lot more like Esterhazy than they are like Smith. She lived in the Potteries and she had fairies at the bottom of her garden. Or rather, at the top; because her garden was the kind that slopes uphill.

The office told me Mrs. Esterhazy had fairies the way you might say somebody had mice or death-watch beetle. I was to go and see her about them. What they didn’t tell me was her address. They knew the name of the road she lived in, but not the number; and when I got there it had ninety-two houses in it, and I knew that if I started knocking on doors methodically I would find that Mrs. Esterhazy lived in the ninety-second. Also it was on a particularly windy bright red housing estate – not a shadow a fairy could hide in, not one toadstool for them to dance round, let alone a fairy ring.

I had to start somewhere, so I knocked at the first door on the right and asked the woman who answered it if she knew where Mrs. Esterhazy lived. I didn’t get the name quite right but I needn’t have worried.

The woman said, “You mean the lady who sees gnomes in the garden?” in the matter of fact sort of way that you’d say: “Is it the one who does dressmaking?” She directed me to the first house past the corner. It looked about twice as clean and light and bright and no-nonsense as any of the other ninety-one houses, which was saying a good deal, and I didn’t see how Mrs. Esterhazy could possibly live there. By this time I had a very precise mental picture of her. She was tall and dark and rather fey-looking, with amber beads and one of those large rings that look as if something will happen if you rub them.

And then, when Mrs. Esterhazy opened the door to my knock she looked remarkably like a games mistress we used to have at school. She was a nice games mistress, but she wasn’t fey, and neither was Mrs. Esterhazy. You could imagine her saying: “One-two, one-two!” crisply, rather than “abracadabra”. She wasn’t wearing amber beads; just one row of pearls with a red cardigan, and her only ring was a wedding-ring.

She invited me into one of the most sensible sitting-rooms you’ve ever seen, with three very solid wild ducks in flight across one wall, and she began telling about the Little People as simply as if I’d come from the grocer’s and she was giving her weekly order.

Apparently she had looked out of the window one day and seen a Little Face smiling at her out of the hedge. If you look hard enough it’s fairly easy to see faces smiling at you out of hedges, and I thought that was what must have happened to Mrs. Esterhazy, especially since she said it had gone before her husband could see it.

But then she told me about the next Little Person. He was 12 inches high and he was “sitting on the edge of that table just behind you”. I got a crawling feeling in the back of my neck. It would be too silly to turn round, but I squinted quickly backwards when Mrs. Esterhazy glanced away for a moment. It looked quite an ordinary table. She went on to tell me that her husband had seen the Little Person too, and he was a chartered accountant. That clinched it. A lawyer or a doctor or a policeman or even a bishop might see Little People that weren’t there; but not a chartered accountant. Not possibly.

I was lost after that. When Mrs. Esterhazy told me about the night 150 Little People came into her garden with lanterns I could hear the pattering of their feet. I did have one moment of doubt when she began to tell me about her earlier experiences. She had gone into a church one day and saw kneeling in front of her the figure of a nun in grey. I was opening my mouth to say that you were liable to see nuns in churches, and they probably would be saying their prayers, and some of them did wear grey, but Mrs. Esterhazy got in first.

“And suddenly,” she said, “she was gone! Pouf! – like that!”

So I gave up trying, I just listened to details about the Little People, the ladies with their gossamer dresses, every colour of the rainbow, the gentlemen with their little trousers of green and brown. Mr. Esterhazy came home about halfway through, and you could see he was a chartered accountant as soon as he opened the garden gate. He believed in the Little People too.

Or did he just believe in his wife’s Little People? I didn’t know. I don’t really know now. But I understand exactly how my grandmother in North Wales could not believe in fairies and at the same time believe in her grandmother’s fairies. Because if anybody asked me if I’d ever seen the Little People I’d say, “No”. But I’ve seen Mrs. Esterhazy’s little people. I’ve even felt them in the back of my neck.”

***

But my old editor was right. In one respect, anyway. It still is a tough life for a woman! She is competing with men in one of the trickiest games on earth. On equal terms and with no special favours. And she wouldn’t have it any other way. Nothing riles a woman reporter like being told it’s ‘half-way for ladies’.

Ann Sharpley has had plenty of experience of that. And as a busy feature-writer on the London Evening Standard she has developed her own technique for dealing with pompous males who don’t want women around.

I first became aware of Anne long before I ever met her. I was sitting up in bed waiting for a broken leg to heal and moodily flicking through my paper and wondering how they could possibly fill it without me when I came across a profile of Orson Welles written by a girl I had never heard of.

A ‘profile’, in newspaper language, means a word-picture of a personality. Orson Welles is certainly a personality: and the ‘profile’ writer’s delight. But this writer had caught him in a deliciously revealing mood. She had come across the great man eating a boiled egg in an arty-crafty tea shop at Haworth, of all places; and in between spoonfuls, delivering an impromptu lecture on the Brontë girls, to a party of astonished tourists who must have got quite a new slant on life in Haworth Parsonage.

This was all so delightfully different that I had to write off there and then to say so. (And writing isn’t all that easy when you are encased in plaster to within six inches of your adam’s apple.)

So that was how I heard of Anne Sharpley for the first time. Afterwards, of course, I heard quite a lot about her. The last time we met was at Grace Kelly’s wedding during that merry, mad fortnight at Monte Carlo. Since then she has covered all the Royal Tours for the London Evening Standard, spent six months in America as roving correspondent, and motored to Russia.

On all these assignments she was competing with men at their own game.

“I don’t honestly think”, she says, “that there’s much difference between men and women when actually doing the work. I think there are differences of character. I think, for instance, on evening-paper work it’s important to be able to think, write and run very fast; preferably all three together. But these are not necessarily male or female characteristics.

“You need a good nerve and don’t have to mind flying, flophouses or fools. But I can’t think of anything that brilliantly illustrates the male-female difference – except that I’ve twice got into a harem (as a visitor!) which male reporters don’t easily manage.

“I suppose the obvious advantage of being a woman reporter is that one is assumed to be able to vamp oneself in and out of any given situation. Let me tell you straight away this just isn’t so. The first sign of any siren-like tactic and you’re lost. In fact I remember one tough and famous war correspondent virtually telling me to remove my nail varnish. There’s a favourite Russian proverb of mine all about having every day to prove you’re not a camel. Well, I have found that in dealing with the British, and the British Army especially, you have to prove every day that you’re not a vamp. I remember when I was covering the Cyprus situation wherever I went a certain very tough paratrooper always seemed to be on duty.”

“’Look out, here comes Mata Hari,’ I’d hear him saying. ‘Don’t tell her nuthing.’ When you’re on a very short deadline, as I am on a London evening paper, with editions going away all day up to nearly four o’clock, you have to be very nippy.”

“Then of course there’s the adamant official attitude to women in war. When I applied to land with the British at Port Said, which I had every right to do since I had been covering the Canal story and most of the Middle East, I was told it was hopeless.”

“They did devise the most gallant sounding excuse for their lack of impartiality. ‘It would make the chaps so nervous about you. They’d feel they’d have to protect you all the time.’ And that’s as far as I got . . . although I was allowed to commute from Cyprus as often as I liked after the landing.”

“Considering this country’s outstanding record in producing women of courage and character you’d have thought they might have taken a slight risk on me, especially as I’d just arrived fresh from another war – the Israeli-Sinai desert war.”

“With the Egyptians it was the same story in reverse. They refused absolutely to notice my existence. When I got the idea of seeing General Neguib, the imprisoned figurehead of the Revolution in Egypt – a kindly, much-loved man ruthlessly deposed by Colonel Nasser – I went along early one morning to the house where he was kept under arrest – and was promptly arrested myself. I was released on the grounds, I’m convinced, that being only a woman I couldn’t possibly have been up to anything.”

“Then when I made up my mind to find the Nazi propagandist, Johann von Leers, who was somewhere in the ten-storey-high propaganda building, pouring out practised hatred against the Jews, I fell back on an old device. Unlike men, I never make the mistake of under-estimating other women. At the hotel where I was staying there was the usual multi-lingual, plump, kind-hearted telephonist. I asked her to ring up her opposite number on the propaganda switchboard and ask for the ‘little white-haired foreign gentleman’ giving no names, just the description, as though the real name had just escaped her memory – as I knew Johann von Leers was working under an alias.”

“Sure enough those two voluble warm-hearted ladies sorted out my problem; and what in fact was an extremely important secret was divulged in the way of ordinary chit-chat. I now knew which floor to make for in that ten-storey building. Now, being a woman it was relatively simple to get through all the armed guards. I just walked very fast and they pretended not to see me. So I went along, opening and shutting doors, with the guards staring sleepily at me – until I opened the right one; and there was the little German propagandist, who had also become tinged with this underestimation of women that afflicts the Middle East, and we’d had a long, if slightly insane chat, before it occurred to him to wonder who I was.”

“Unwilling at that time to throw me out of their country because of the bad impression it would make, the Egyptians decided once again that being a female what they’d better do to scare me was to threaten me. So a number of hair-raising threats were delivered to me by an official about being beaten up and/or dropped in the Nile, or my bruised and broken body put outside the gate of the British Embassy. That, they supposed, would settle everything. When it didn’t work out, and I didn’t scream and faint but continued finding out more and more of what they didn’t want finding out, they threw me out of Egypt. We had a lovely farewell at the airport. All the other correspondents came up to see me off and several smiling Egyptian officials stood around to make sure I got on the plane.

“But I must say I like Egyptians for their sense of humour. They really do have a delightful sense of humour, you know. Because when ten days later I had to fly through Cairo again to get down to Nairobi to cover Princess Margaret’s trip to East Africa, I played a very mild prank. I wasn’t really supposed to land in Egypt at all. I was supposed to stay sealed ‘In Transit’. Instead I did my old trick of being an invisible Woman, walked briskly through the line of sentries, and called on the officials who had seen me off ten days earlier. They were terribly amused and bought me a drink; then I marched briskly through the guards again and caught my ‘plane to Nairobi'”.

***

And so it goes. From fairies to fire-raising. From banquets to bunfights. The Woman Reporter is there on the job. No royal wedding, no revolution, would be complete without her.

Nice work, if you can get it? Perhaps. And it’s a great life. If you don’t weaken. . .

Note: The tile is, I assume, a reference to “Ladies Half-Way and Other Essays” by Basil Macdonald Hastings, published in 1927, although I have been unable to find out any more. Jerry F

Jerry F 2022