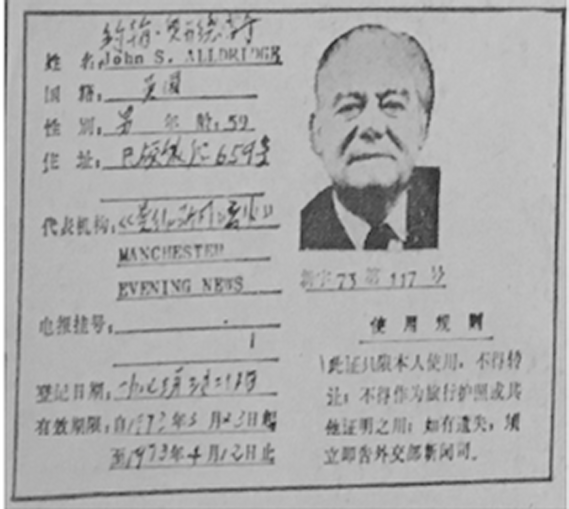

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

I drove out to Pekin’s Tsingua University in the same staid old Shanghai which had brought me in from the airport. The Shanghai, so called because it is made in that city, is one of China’s two locally bulit cars. It looks rather like an old-fashioned Vauxhall. The other is the much more opulent Red Flag, which is built more like a Daimler. Since both are heavily upholstered, dripping with lace antimacassars, and with side windows curtained, driving around Pekin you aren’t sure whether you’re going to a wedding, a funeral, or a top-secret Summit Conference.

But only the privileged few drive around in cars anyway. For the rank and file, the bicycle is the commonest form of transport. During the rush hours – eight o’clock and again at five – the city is abuzz with bicycles rolling sedately all over the streets that, following the compass points, run due north, south, east, and west.

Little Comrade Wu, my interpreter and faithful shadow, who has never left me except to sleep since he picked me up at the airport, tells me that there are no less than 1,700,000 bicycles in Pekin. And I can well believe it. A good one – the sort that grandma used to ride, bolt upright, with a mudguard protecting her skirt, costs 150 yuan, or about £30 – two months’ pay as far as Comrade Wu is concerned. And although of course there are no bicycle thieves now in the People’s Republic, Wu always locks his up securely when he leaves it at a bicycle park, just to be on the safe side. To lose his bicycle would be a disaster for Wu, who cycles 20 minutes to work and 20 minutes back every day of the week except Sunday (by the way, no Pekin bicycle seems to carry lights front or rear, which makes driving at night here in Pekin a real nightmare).

So we drove out to the University through drab, dusty monotonous districts, half residential, half industrial, with nothing to show where the barrack-like worker’ flata leave off and the factories begin. But the roads are good and ideal for bicycles; flat and hard and in good order. What bothered me was the fine, acrid dust which seemed to hang heavy over the city all day. After only two days of it, I was coughing and barking just like Comrade Wu.

I know now why everywhere you see ubiquitous white-enamelled spittoons – which looked at first sight embarrassingly like a chamber pot. Wu tells me I that the dust comes from the Gobi Desert. Now it may be kind of romantic to know that the fine dust that fills your shoes and lines the bottom of your bath and clogs your nostrils blows all the way from the Gobi Desert. But it’s irritating to spend half your time coughing and spluttering as if you’ve got chronic bronchitis: and I know now why so many workers coming in from suburbia and driving around in open trucks wear white face pads rather like smog masks, to keep out the fine, ever-penetrating dust.

We were met on the steps of the University by the Vice-Chancellor, or as they call him here, the Chairman of the Revolutionary Committee; a small, stocky figure in a thick black mushroom-like cap pulled well down over his eye-brows and a long black overcoat almost down to his ankles which made him look at a distance rather like Chairman Mao himself.

He welcomed us most graciously, Introduced us to his staff, of whom three were women, and hurried us off into the conference room, where we sat in heavy upholstered armchairs – drip-ping with antimacassars, of course, and sipped cup after cup of refreshing green tea while he explained how they ran this university with its 11 departments of science and engineering, much of which dates from the 50s and 60s.

Like all universities in the People’s Republic, Tsingua University is just recovering from the convulsions of a violent educational revolution. For two years between 1968 and 1970, the university enrolled no pupils at all. Today there are 2,800 enrolled in 1970, in the middle of a three-year course and another 2,500, the class of 1972, just ending its first year. About 5,000 students in all.

The reason for this hiatus was the Cultural Revolution, which completely revolutionised higher education in China.

What prompted the Cultural Revolution was the sudden realisation in that shrewd old mind of Chairman Mao that education was slowly creating an elite middle class to his way of thinking, the hated bourgeoisie was threatening the future of the broad masses of the people. The favoured few were those with a university education. High marks in a routine examination usually meant top jobs in a Ministry. Mao knew better than anybody that this has been China’s oldest curse, the brilliant student who, because of his high academic success, obtains automatically a responsible post in the government for which he might be completely unsuitable.

The literature of China is full of stories of poor men setting out along the path to glory through a series of tiny examination cells; with little money, a long way to go, but with Confucius on the brain and the future in a writing brush. Everything was based on the provincial examinations held every three years; and if the wonder boy from the village could please the examiners with an essay, he passed on to the metropolitan exam in the capital itself. This examination over, the now very senior scholar (he could be any thing from 25 to 55) entered for the Palace exam. Brilliant careers were assured for those who passed, the lowest of which was a magisterial appointment in the provinces.

Thus it was for hundreds of years in China and to his dismay the Chairman could see it happening again in 1964. But let the head of the revolutionary committee explain: “Before the cultural revolution the post-graduate student had to study for 21 years from primary school. During that time he had no contact with the masses. Our aim now is to make students develop morally, intellectually, and spiritually. This is very different from the old days, when the emphasis was on book-learning. They learned from books, but didn’t know, how to do it. Now the students work in factories and put their theory into practice.”

Initiative not swotting

What this means, in effect, is that examinations and an inflexible marking system. have been scrapped. Would-be university students who have worked at least three years in a factory or in a commune after leaving high school, must be nominated for a university place by their union, farm, factory, or army battalion. Nominees are then allowed to study the examination questions in advance, consult with their teachers, and do their own research. Answers to questions are based on personal initiative, not on swotting. And if the results satisfy the university selection board, then he or she may offered a place. But only on condition that after the three-year course, reduced from the original five, the post-graduate returns to do another couple of years in the factory, farm, or army unit. “In this way,” says the head of the revolutionary committee, “contact with the masses is never lost”. I should add that while studying a student gets his normal pay made up. Tough on the students? Undoubtedly, particularly when the People’s republic sternly disapproves of youthful marriages and makes no accommodation available on the campus for married couples. There is hard sense in this. After graduation man and wife may find themselves living and working a thousand miles apart.

But it is tough, too, on the teachers. The head again: “Chairman Mao has said that the chief problem of education is the problem of teaching.Before the Cultural Revolution teachers treated students like animals. They were content to cram them with book-learning until they burst. High marks for everything. In doing so the teachers were only concerned about their own prestige.

“The Chairman has said that those who teach should be educated first. Therefore teachers must learn from workers, peasants, and students. In other words, teachers under the new regime must do a spell in the factories, too, to find out what it’s all about”.

In the hydraulic-engineering department I saw students working on a large-scale model of a dam designed to serve a new oil refinery 500 miles away. This was no draughtboard pipe dream. The students had done six months’ field work on the actual site and their plan has just been passed for construction by the State.

The point of this being that all of these students had been practical engineers before they became engineering students.

Essentials demanded for a university place in the new China are, in that order, a high political conscience, a good middle-level education, two or three years’ practical experience in a factory, farm, or in the army, and Al health. In this there are no exceptions; which makes it hard on would-be chemistry students who happen to be colour-blind. They are automatically disqualified.

After all this revolutionary talk, and still thinking furiously, I visited an English class, where I was greeted with the usual clapping and invited to sit down and talk. I found myself talking a slant-eyed lass with a face as round as a full moon who came, she to me, from a farming commune in Mongolia.

She spoke English better than most Mancunians, but had obviously never heard of any English author later than Dickens. She told me she had been studying English only 10 years and had got much help from tapes loaned by the BBC. I asked her what she would do when she graduated. “I hope I will be sent back to my commune to speak English,” she said proudly.

Dickens — in a village in Mongolia? It was quite a thought. I visited the library, a severely functional building where dozens of youngsters, many in army uniforms, girls as well as men, were studying yellowing newsprint cuttings in English, Russian, and Chinese. They showed me the rather battered English collection: Dickens again and Scott. Victor Hugo and Defoe. And – strange bedfellow – Jack London.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file