The Mysterious Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe

In the early hours of Thursday 17th March 2022, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe arrived at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire after a near six-year-long detention in her native Iran. Part of the time she was kept in the Evin jail in Tehran, part of the time tagged and under house arrest at her parent’s Tehran home and part of the time in jail in Kerman in the south of the country.

Back in the UK, the charming and dotty Hampshire in-laws of the mother of one toured the studios announcing they were going to clean a family apartment sadly neglected by their son. Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe phoned ahead to ask for a nice cup of tea. The following morning, the newspapers reported that seven-year-old daughter, Gabriella, had slept between her parents for the first time in six years.

Used as a state hostage to retrieve a £400 million arms deal debt, falsely accused and convicted in an Iranian court, Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe had been unjustly detained on trumped-up charges based on false claims.

Or had she?

There are two sides to every story and now that Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe is out of an Iranian jail and back in England, both sides of her interesting tale can be examined.

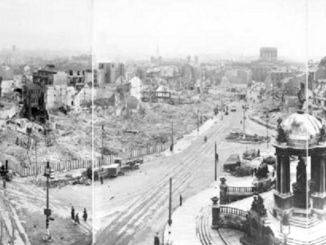

Evin house of detention,

Ehsan Iran – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Nazanin Zaghari was born in Tehran on Boxing Day 1978. After graduating in English Literature at the University of Tehran, she taught English, did a tour of NGOs and then travelled to London, aged 29, as a scholarship student studying for a Master’s degree in Communication Management at London’s Metropolitan University.

She married Richard Ratcliffe in August 2009, after being introduced by mutual friends, and added a British passport to her Iranian one in 2013.

In 2016 she was arrested at the end of a family holiday in Iran after showing her twenty-two-month-old daughter, Gabriella, to her parents for the first time. Described in the British press as a ‘charity worker’, the charity concerned was the Thomson Reuters Foundation which, according to its website,

“Works to advance media freedom, raise awareness of human rights issues around the world via our news coverage and by training local journalists to report accurately on these issues.”

An overtly political foundation, its mission statement includes the following,

“There is increasing recognition that the mainstream economic model is generating a deepening divide and hurting our planet. Modern slavery, the climate crisis, and the impact of data and technology on people are among the biggest challenges of our time.”

Trustees include Geert Linnebank, a director of ITN, Brian Peccarelliceo and Mary Alice Vuicic both of the Thomson Reuters parent company and Margaret Mendi Njonjo of the Hivos organisation, a civil society NGO linked to George Soros.

During their investigation, the Iranian authorities quickly established that Zaghari-Ratcliffe had also been a BBC employee via, amongst other things, a payslip and redundancy notice found in her possession.

The Thomson Reuters foundation turns over about £13,000,000 a year. Interestingly, it benefitted from £549,000 of UK Government grants in the year before Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s arrest but only £166,000 the following year and £31,000 the year after that. This begs a question. Was a UK Government operation, organised through the Thomson Reuters Foundation ended by the arrest of Zaghari-Ratcliffe?

Reuters and the BBC have form.

Reuters, the BBC & the IRD

Starting in the 1960s, Reuters (so-called before being acquired by the Canadian multinational media conglomerate Thomson) was used by the Foreign Office’s Information Research Department – known as the IRD. The IRD had been set up in 1948 as a Cold War propaganda department of the British Foreign Office. With close ties to the intelligence services, the IRD was tasked with providing information to be used as propaganda to counter Communist activities in Western Europe, British colonies and elsewhere across the globe. A clandestine organisation, its existence wasn’t made public until after it had been abolished in 1977.

Carefully selected journalists and opinion formers were introduced to the IRD discreetly, being told as little as possible about the organisation. Meticulously researched and slanted anonymous copy was passed to them to incorporate into, or pass off as, their own published work.

Government papers de-classified in 2020 showed that in the 1960s and 1970s Reuters was part of the IRD’s Middle East propaganda effort. This operation was funded secretly by the BBC overpaying for the use of Reuter’s services. At the time, the BBC World Service was paid for directly by the Foreign Office rather than from the licence fee. As the declassified papers explain;

“What HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] might secure, in effect, is the chance to influence in some measure the whole Reuters output. There is here the opportunity to evolve a relationship between Reuters, capable of preserving the Agency’s [Reuters] independence of government control, while at the same time giving HMG a measure of political influence”

Set up as a new Reuters Middle East news service, it replaced the IDS’s own Regional News Service (Middle East). The new operation competed with Egypt-based Middle East News Agency, Soviet agency Tass and Agence France Presse. The object was to surreptitiously control news output while avoiding being accused of controlling a news outlet.

The IRD was wound up by a squeamish James Callaghan administration in 1977 following concerns its remit was being exceeded. Nervous about detente-era anti-Communism, independence-era support for colonial powers and aware the IRD were prying into Soviet infiltration of the Labour Party and Trades Unions, Foreign Secretary David Owen replaced the IRD with a leaner organisation, under closer political control, known as the Overseas Information Department.

With the exponential growth of the internet, social media and digital TV, the Foreign Offices’ information effort has mushroomed. These days one hears tell of such things as the ‘Islamic Media Unit’ and the concept of ‘Public Diplomacy’.

Nazanin and Richard Ratcliffe – New Year’s Day 2011,

Mr Zero – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Zaghari-Ratcliffe & the BBC

Zaghari-Ratcliffe worked for BBC World Service Trust (which became BBC Media Action in 2011) between February 2009 and October 2010, immediately after completing her Master’s. At the time, the BBC World Service was still funded by the Foreign Office.

Despite her higher degree in Communication Management, being a native Farsi speaker and her degree in English Literature, a BBC Media Action press release at the time of her arrest claimed she was employed in a junior administrative role insisting,

“Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe was never a journalism trainer but undertook administrative duties such as travel bookings, typing, and filing.”

However, her payslip puts her in the middle of the BBC journalist pay scale. It also includes her address which places her in an exclusive part of North London. One of daughter Gabriella’s playmates is the child of hereditary BBC lifer Victoria Coren Mitchell. Unaffordable to a junior administrator, one wonders of her real occupation and that of her husband.

Described as a North London accountant, spouse Richard Ratcliffe is also in government service as a National Audit Office accountant seconded as a staff member to the International Development Committee which nowadays is also part of the Foreign Office.

ZigZag

According to the Powerbase website, the Overseas Information Department was replaced in 1980 by the Information Department which was in turn replaced by the Public Diplomacy Department in 2000. To understand Nazanin Zahari-Ratcliffe’s role in the propaganda warfare effort against Iran we must fast forward to 2006.

By then, although Iran contained the necessary infrastructure, technology-based internal dissent had not been mobilised. Iran was a closed country with good internal internet but not enough anti-regime activists trained in ‘Public Diplomacy’.

Given the difficulty of face to face instruction within the country, the BBC World Service Trust set about training volunteer journalists, under the radar, using long-distance mentoring, online learning modules (via BBC iLearn) and an online magazine called ZigZag. Suitable candidates would progress to face to face training abroad in, amongst other places, Turkey, India and The Netherlands.

At the outset, the BBC received 1,000 applications for an initial 60 training slots. Between November 2006 and October 2007 the ZigZag site had 800,000 visits and 2.4 million page views. 58% of visits were from within Iran. The goal was to train journalists rather than create a publication, with a key statistic being that 2,500 users had registered by late 2007. Although the programme was supposed to be under the radar, comment within the existing Iranian blogosphere began to raise its visibility.

ZigZag had private and public forums containing ‘soft’ articles aimed at a younger audience. BBC Persian (then a radio service) disseminated political news and views with ZigZag ostensibly more entertainment and social and cultural issue orientated. The public forums allowed anyone to post while the private forums were where trainees received online help from BBC mentors. That mentoring included being kept ‘on message’ while being moved away from soft issues towards news and features.

A panorama picture of north of Teheran in a clean day after a rain,

Amir Pashael – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

ZigZag was the successor to a 2002 American project called ‘Cappuccino’ which had been more strident in its anti-regime propaganda. Soon blocked in Iran, it fizzled out. ZigZag benefitted from greater scope than Cappuccino and was also supported by a weekly two-hour-long radio show created by trainees who were guided by a BBC producer.

Old Cappuccino hands were dismissive of ZigZag, assuming correctly it would soon be blocked and, with few able to access, its influence would be limited. The counter-argument being that, five years after Cappuccino, sufficient young Iranians were now proxy and cache tech-savvy enough to circumvent the blocking.

Another part of ZigZag was ‘Media Watch’, funded by the Dutch Foreign Ministry. This would be a slanted verification system similar to the present-day BBC so-called ‘Disinformation’ effort, fronted by Puffin’s favourite Marianna Spring.

Fatally, while applying for permission to bring a promising candidate to London, BBC World Service Trust sent a message to the British Embassy in Tehran in support of a visa application. Such visitors have to be sponsored and the sponsor has to be able to support the visitor materially during their stay.

The 11th February 2009 BBC World Service Trust communication named Nanazin Zaghari as the sponsor for the visit to London of a ‘friend’. In direct contradiction of what the BBC would claim following her arrest five years later, our Tehran embassy was told Ms Zaghari was employed as a Training Assistant for the BBC World Service Trust, Iran Project, and had a permanent contract with the BBC.

Privacy advocates Article19 claim that such information was extracted by the Iranians from Ms Zaghari’s emails after her arrest. This is one possibility, as is the ubiquitous postal interception that takes place in Iran.

In this author’s previous life more interesting, long before the internet, letters from Iran had always obviously been tampered with via the rotating knitting needle curling the contents through the top of the envelope trick.

Another possible source might be via documents stolen from the British Embassy when it was stormed by a mob in 2011 protesting over UK sanctions against Iran’s nuclear programme.

The Iranians are well known for intercepting, copying and archiving everything. After Iranian students occupied the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, they gleaned important intelligence by spending years painstakingly glueing together everything the Americans had put through the shredders – even some material that had been burned.

An early test of the ZigZag project was to be the 2009 Iranian elections. A wall of regime derangement syndrome social media and blogging content was envisaged, framed by Information Research Department style spin. Although the opposition did well in Tehran and the south, elsewhere sitting President Ahmadinejad won handsomely, sparking protests in cosmopolitan parts of Teheran and some other cities, amplified by Western media, which ultimately came to nothing.

Critics within Iran complained ZigZag was easy to block and obviously an MI6 set-up. It was colonialist and too focused at the Tehran middle-class. In targetting young people dissatisfied with the Iranian regime, its remit was narrow. It was further tainted by association with the British ‘Old Fox’, an interfering former colonial power connected with the hated Shah while allied to America and to Iran’s ethnic, religious and military rivals at the other side of the Persian Gulf in Saudi Arabia.

ZigZag was put out of its misery in 2010. As if a virtual dank Cold War bunker on an East European hillside, all that remains is an abandoned website domain, another domain cheekily hijacked to advertise Dutch cannabis and an empty Twitter account with two followers.

BBC Persian TV presenters Majid Afshar and Rana Rahimpour,

Persian Dutch Network – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

The Cases Against Zaghari-Ratcliffe

The end of ZigZag overlapped with the BBC’s new Persian TV service which started in 2009. Produced in London with Iranian staff, it was difficult to block as it was transmitted by satellite. As ZigZag was phased out, Zaghari’s role changed to recruiting for the new Persian service. Issued with a redundancy notice in April 2010, she was to move effortlessly to a similar propaganda warfare training scheme with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, at first glance a greater arm’s length from MI6, the BBC and the Foreign Office.

While working her notice, Zaghari-Ratcliffe sent an email asking to shadow Sanjay Azim Nazerali, Director of Marketing, Communications & Audiences at BBC News. Nazerali was to become a trustee of BBC Media Action in 2015 and subsequently a member of the New Economic Forum.

In this email, which subsequently fell into the hands of the Iranian secret service, Zaghari-Ratcliffe says she is a training assistant at the BBC World Service Trust, Iran team, with ZigZag Academy which ‘trains young aspiring journalists from Iran and Afghanistan through a secure platform’. She claimed a significant role,

“Organising face-to-face training courses, selecting trainees and assessing them with starting up on the platform, managing and mentoring the trainees’ performance, monitoring the journalist mentors in both Iran and the UK; organizing face-to-face training at the end of each online training course, co-ordinating administrative/finance support to the Iran team, collaborating closely with the Research and Learning team for project feedback etc.”

All the beans having been spilt, the Iranians were able to successfully prosecute Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe for plotting to topple the Iranian regime. She was sentenced to five years in prison in September 2016. To confirm Iranian suspicions, in November 2017 the then foreign secretary Boris Johnson told the House of Commons foreign affairs committee,

“When I look at what Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was doing, she was simply teaching people journalism, as I understand it.”

Ironically, having ranted about alleged Russian interference in the Brexit Referendum and 2016 Trump presidential win, the Foreign Office and the BBC had been caught trying to do just that in Iran.

Previously, in 2014, ZigZag was mentioned in dispatches when eleven website and media content providers in the southern province of Kerman were jailed for producing anti-state and anti-Iranian media. According to The Guardian newspaper, at least one had participated in a ZigZag training course.

In January 2019, Iranian State TV made more allegations against Zaghari-Ratcliffe, that she received $11,000 a month from an organisation called The Training Station which is funded by the Foreign Office and delivers training for the British Council and BBC Media Matters. Her work there allegedly involved setting up false internet accounts and teaching encryption and counter-interrogation techniques.

In November 2020 she faced fresh charges of spreading propaganda against the Iranian regime and in March 2021, just after ending her original sentence (some of it spent under house arrest because of Covid), she was in court again and given another year in jail regarding propaganda activities relating to an interview with BBC Persia and a London demonstration 12 years previously.

On 16th March 2022 she was finally released, coincidental with the settlement by the UK Government of an historic £400 million debt regarding undelivered armoured vehicles originally ordered by the Shah.

What does the future hold for the mysterious and interesting Mrs Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe? She ticks many boxes, now including, rightly or wrongly, ‘victim’. Expect further gushing press coverage followed, perhaps, by a career in advocacy or even politics.

References & Further Reading

Al-Monitor, Case for Jailing British-Iranian National

Article19, Unlawful Detentions

BBC, UK Secret Funding of a Middle East News Agency

Foreign Office, Present-day research effort

The Guardian, Iran Website Staff Jailed

The Guardian, Death of a Department That Never Was

The Guardian, Secret Unit Used to Smear Union Leaders

MediaShift, BBC Trains Iranian Journalists

Powerbase, The Information Research Department

PressTV, Western Narrative About Zaghari-Ratcliffe Challenged

Reuters, Britain Secretly Funded Reuters

Wiki, The Information Research Department

© Always Worth Saying 2022