To a newspaperman, I suppose, the real excitement of a special assignment is its glorious uncertainty. Like lightning, it never strikes the same place twice.

A couple of summers ago I was sunbathing on the rocks in Cornwall. I had not a care in the world. All I wanted just then was to lie there for a million years with the sun on my back. And so Fate chose that precise moment to hand me a telegram. A telegram that went something like this:

YOU LEAVE FOR KARACHI SEPTEMBER 27TH STOP YOU WILL NEED A SLEEPING BAG STOP YOU WILL GO ARMED STOP EDITOR MANCHESTER EVENING NEWS.

That’s all and, though I couldn’t know it then, that telegram was to send me a quarter of the way round the earth, at never much more than 20 miles an hour, over one of the worst roads in the world, which for about 200 miles isn’t a road at all. It was to take me to places I had never heard of. To places with names I can’t pronounce and still don’t believe really exist. It was to take me over mountains and across deserts and through floods. Living for days on tea and watermelon and hard-boiled eggs. Roasted by day and frozen by night. For thirty-five unbelievable, indescribable days.

It was all because three enterprising Pakistani gentlemen had the bright idea of running a bus service from Manchester, England to Karachi, Pakistan and wanted to prove it could be done.

For them it was a matter of business. For me it was just a job. A story. A Special Assignment. At the time I hated almost every minute of it; but I wouldn’t trade the memory of it now for all the tea in China.

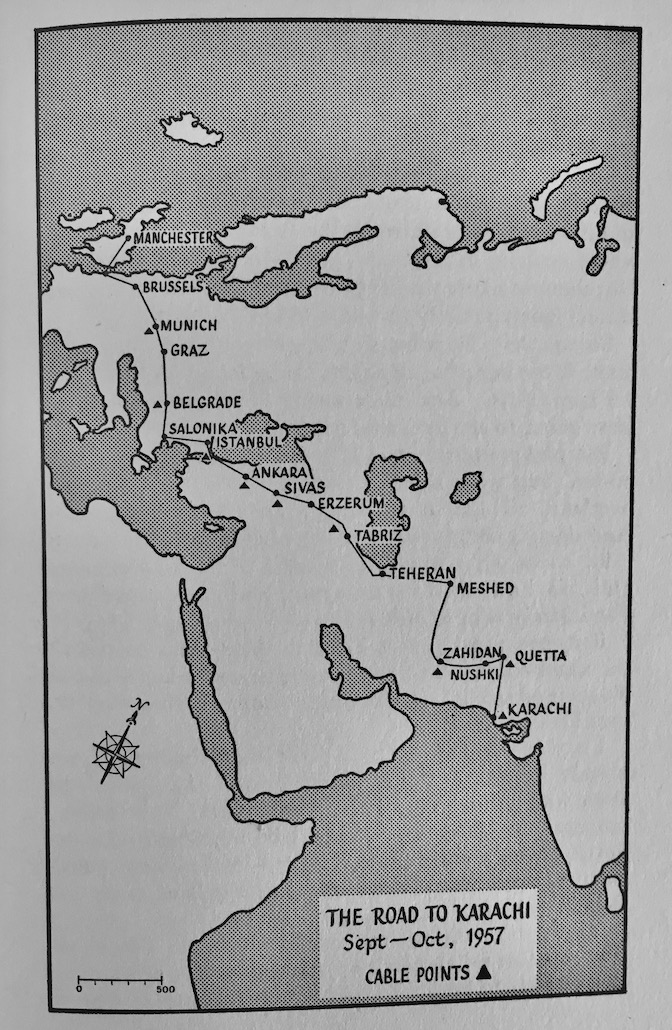

I still shudder when I look at the map and remember what we attempted – without having the faintest idea what we were letting ourselves in for.

If there exists anywhere in the world a longer bus ride than this one – please don’t tell me! This one is quite long enough. There is 6,500 miles of it, all told.

It crosses ten countries and one-and-a-half continents. The first 1,000 miles or so are easy enough. You cross the Channel, find your way up to Cologne and then go buzzing down those wonderful German autobahnen all the way to Saltzburg. Then you nip across Austria as far as Graz; and dive into Yugoslavia, where your troubles really begin. For the 200 miles of heartbreaking, axle-shattering road between Nis and Skopje is the worst part of the whole ride. Four days later – if you are lucky and are still on four wheels – you come out again into Greece; then you are all set to go sliding and slipping round the corner into Turkey. From Istanbul you cross the Bosporus in something like the Mersey ferry, and there you are in Asia: with 4,000 miles still to go, and nearly a thousand miles of it desert. And when it isn’t desert you are climbing up some of the toughest, most obstinate mountains to be found anywhere in the world, with a hair-pin bend every few hundred yards, and a view round the bend that makes your stomach turn over.

Out on the desert it’s as hot as a bake-house door by day; and at night so cold that even under five blankets you are still frozen stiff.

For hours on end you never see a living soul. In fact there is one stretch—between the Holy City of Meshed and Zahidan, right down on the Persia-Pakistan border, where nothing lives at all. Just 200 miles of salt desert. Out there at night you might be travelling across a moon crater: lonely, utterly lost, in a long-dead world. . .

So we were planning a bus service. We planned to make it the best, the cheapest, the quickest and the safest we knew how. And since seeing is believing – well, we were going to see for ourselves.

We had to prove that it really is possible to take a 10-ton bus with thirty passengers and their baggage overland all the way from Manchester to Karachi. And since it had never been done before we had to learn a lot about what would be needed in the way of petrol and oil and food and water and accommodation. Particularly accommodation.

For once you are past Teheran there is no hotel for a thousand miles. You eat what you can when you can. You are often choked with dust. And a bath a week is a rare luxury.

I say “we”. But really I don’t come into it. I was merely a reporter going along for the ride. Even so, there was nothing special about any of us. Not a Hillary amongst us. Just two Pakistani businessmen who had never driven a car outside England in their lives, and a reporter who won’t drive even in England if he can help it.

There was nothing very special about the car, either. She was just an elderly 18 horse-power dowager whose first owner had been a Lord Provost of Glasgow. And she looked it! Even with a brand-new engine in her, and her suspension lifted a couple of inches, she still looked what she was: a comfortable old lady whose touring days were over. We called her The Duchess, and no car was better named: she took us a quarter of the way round the world without so much as a whimper. A very great lady, The Duchess.

As for equipment – well, I remember a tent which remained stuck like a sausage in its skin until we had to put it up one night in the dark in the middle of the desert. (What happened then was like something straight out of Three Men in a Boat.)

I seem to recall a pink plastic bucket with a hole in it. And a wonderful collection of kitchen gear, including my daughter’s Girl Guide mug. And at least a thousand water-purifying tablets.

I brought along my typewriter, two cameras and a double-barrel shot-gun complete with seventy-five rounds of swan-shot. And a travelling wardrobe that covered everything from a duffle-coat and balaclava helmet to shorts and mosquito-nets. As for my companions, their personal kit consisted of what they stood up in and an 1 extra shirt and pair of socks, shared between them!

We did have the sense to fix a spare 16-gallon petrol tank on the roof; and took along four 1-gallon plastic water containers. But we had no maps, and only the vaguest idea where we were going. By and large, we must have been the worst-equipped expedition ever to leave these British Isles. By rights, of course, we shouldn’t have got beyond Belgrade. But we did. And the odd thing is – looking back on it now, I believe we enjoyed it. Or most of it, anyway. There were a couple of days in Persia, watching the flood water rising under us, when I would gladly have sold the lot for an air passage home. But it provided me with a graphic little “colour” piece for my paper:

“A few hours of rain and every bone-dry gully, brook and rivulet in Persia springs chuckling and chattering into violent life.” (I cabled.) “After a whole night of it acres of desert are under water, a vicious torrent rushing down on the helpless road. It has been raining steadily for forty-eight hours. We seem to have run into something called a freak monsoon, I never want to experience another. This is the East Coast floods all over again.

“For twelve hours, since long before dawn, we have been picking our way along the 200 miles of road from Tabriz to the capital; a road which for hundreds of yards at a time has completely disappeared under the sullen brown flood.

“Every few miles it is washed out by a foaming river of mud and water over a foot deep in places. A river which must be forded somehow, anyhow.

“It is a brave sight to see the Old Lady daintily lift her skirts and go waddling across where even huge six-wheel petrol bowsers hesitate.”

But somehow we got through, and on to dry land again. This was largely due to the efforts of a Scots engineer who appeared from nowhere – as Scots engineers have a habit of doing – with a road-gang and bulldozed us a way out.

There were other moments, too. Moments of loneliness which could be very frightening.

“For me the worst thing of all, far worse than this interminable bone-jarring, dust-heavy switch-back of a road, is the sense of isolation, of being completely cut off from the rest of the world, almost from the rest of life”. I cabled in another dispatch:

“We are like a ship in mid-ocean in the days before wireless. We have lost all sense of time and place. It’s an effort to remember what day of the week it is.

“There is only one question now: how far is the next petrol-point and can we get there before dark?

“We have had no news for over a fortnight and no bath for a week. Our skins are sandpaper-rough from the dust. We are living mainly on watermelon and shish-kebab – mutton steaks grilled on a skewer and served with rice and tomatoes. We have run out of tinned milk and are now down to our last packet of tea. But strangely enough we are in good heart. The spirit is willing as we press on regardless.”

Life on that endless, interminable switchback of a road was very curious.

Sometimes you would go for days without passing another human being. And then, suddenly, it would be as busy as the Brighton road on Bank Holiday. The road would be full of them: young men and girls mostly. Whole families of them. Travelling every way; by car, on motor bikes and scooters. We even met one couple who were staunchly hitch-hiking all the way to Australia.

They were something new in my experience, these motor-gypsies. They are a strange, brave breed. Impatient young men from a dozen countries, but most of them from Britain; all heading East to impossible places like Ceylon and China and Honolulu. We would meet and meet again so often that we soon became old friends, though we never learned their names.

After 3,000 miles of it we were glad of their company. For those cruel, cold mountains and stony, sun-baked deserts are frightening after dark. There are places out there where a man stranded with a puncture or a big-end gone could easily die of thirst. So it was comforting to travel in convoy when we could, with the cycles snaking in and out and bringing back news of a bridge washed out ahead or another bullock-cart asleep across the road.

I imagine the old Santa Fe trail must have been very like this in the covered-wagon days. . . .

If I learned anything on that extraordinary bus-route it was this: that there is still an awful lot of friendship left in the world. Out there among those primitive people, where life moves at the pace of a camel, you find it all round you. In those smoky, evil-smelling tea-houses it covers you like a blanket. You are as safe there as you would be in your bed at home. Safer, for all I know.

“I haven’t much to offer. But what I have is yours.” That is the age-old courtesy of the East. And you leave it, ashamed.

A tea-house, or chaikenah, in the Persian sense has nothing to do with four o’clock small-talk after a hard afternoon’s shopping.

It is the nearest the Middle East comes to the old English pub. The door is always open; there is a bed or rather a carpet, spread out on a slab of baked clay – for any benighted traveller.

It is called a tea-house because tea is the only drink served. And like the English pub it is the centre of a vigorous community life.

Here – each sitting cross-legged on his personal carpet, sipping the hot, sweet tea out of tiny glasses – you will find the leading spirits of the village. Chewing over local scandal; or dissecting the far-away news brought in by truck-drivers on the long 500-mile haul from Meshed to Teheran.

These are essentially “stag” sessions. Women there must be, but you never see them. They live an invisible life of their own.

We found such a tea-house about a hundred miles down the road from Teheran, in a village so old, so decrepit that it must have been known to Omar Khayyam, who is buried not far from here.

We were glad to find it, for we had been stumbling along in the dark for hours; and driving at night in country like this, particularly after heavy rain when the most innocent-looking rise in the road may hide a washout a foot deep, is a dangerous business.

We had called at a slack time, it seemed. The locals had gone home to bed, and the rain had held back all but the boldest of the truck-drivers: so they were glad to see us, too, and welcomed us with eloquent dumb-show. With a courtesy I have rarely found in night-porters anywhere in the West they spread fresh carpets for us, brewed fresh tea on the charcoal fire which is never allowed to go out, then left us tactfully to ourselves.

We pulled off our boots and wriggled down into our sleeping-bags and listened for a while to the crickets and the vibrant silence of the desert night. . . .

I have rarely slept better. And in the morning there was more tea and a six-egg omelette, and hot water for shaving, which is something you will not find in the most expensive hotel in Teheran.

Then hand-shakings all round and more fervent salaams before we took the road again just as the early-morning sun slanted down into our eyes from low over the mountains.

From then on for 400 miles the road is one long vanishing-point. There is nothing to do for hours on end but count the telegraph poles and watch the ever-changing play of light on those eternal hills: sometimes slate-grey, sometimes saffron, sometimes old rose, sometimes the deepest purple, according to the time of day.

On we went; through tumble-down villages as old as Norman castles. Past road-menders, shirt-tails flapping over stork-thin legs, who lean on their spades and gesture for cigarettes. Past little boys who spit melon seeds at us. Past a camel who turns her head aside disdainfully, like a duchess who has accepted an invitation to the wrong party.

And then when you leave Meshed, a holy city older than Canterbury, and strike 600 miles south to Zahidan, the border-town between Persia and Pakistan, you are in Kipling’s country.

Just behind you lies Russia. And all the way south on your left hand is the forbidding mountain-wall of Afghanistan.

The mountains suddenly close in until you are almost crushed between them like a walnut.

The road stumbles on in semi-darkness between gorges a thousand feet high and then splashes blindly on through straggling watercourses.

Bearded hillmen – tall, white-turbaned, incredibly fierce – stalk down from behind rocks as big as council houses, driving before them vast herds of goats as fierce and as hungry-looking as themselves.

And any moment, as you disappear into another tunnel-like gorge, you expect to hear the crack of an old muzzle-loader and whining ricochet of a jezail bullet.

Then on and on for miles, over barren, sun-scorched plains covered with a thin rime of what looks like snow but is actually salt.

You smell the salt long before you see it. Shut your eyes and you might be at Blackpool.

The peasants call it the “curse of God”. They believe it was left behind by the Flood which once drowned these plains. That may be so. But certainly because of it nothing grows here – not a tree, not a shrub, not a blade of grass.

From here on it’s a hundred miles between pumps. The few villages you see fit perfectly into the desolate scene. They look like so many collections of mud-pies that have been left in the sun too long.

This was the most depressing, desperate part of the whole trip. Especially at night, when the wonderful mother-of-pearl twilight has slipped down behind the mountain as if ruthlessly switched off in some celestial power-house.

In its last 100 miles in Persia this tortured road almost ceases to exist. It drags its shattered, hopelessly-corrugated length through fifty dried-up watercourses and finally almost loses itself in a waste of sand and salt-marsh where the only signs of life are the herds of wild camel.

And then you are in Zahidan; which has a hotel of sorts and a bath-house. And after a fortnight on the desert you need both badly.

Besides being Persia’s back-door, Zahidan is railhead for the railway to India. A train runs once a week over the single-track straight as an arrow to Quetta.

It is certainly a comfort to have that railway running always beside you night and day; for this is typical North-West Frontier country. Border raids are frequent; any-thing can happen, and often does.

It had taken a horde of officials three hours to get us into Persia. It took a dirty, unshaven customs officer and a couple of pantomime policemen to see us off that poor, ramshackle, police-ridden, open-hearted country. Then for 10 miles we went across no-man’s-land. Ten miles in which you follow a dry river-bed and trust to luck. And then in the middle of a plain as hot as the inside of an oven, where a distant ring of mountains danced and shimmered in the heat, we saw it – a notice-board carrying four words unequivocally English: “Keep to the Left”.

And we knew we had arrived. After 5,000 miles of driving on the right, after nearly three weeks of following a dogged path, we were over the doorstep of Pakistan.

It was an emotional moment for all of us. For Rasal who had not been home for ten years. For Ali, who was too young to remember. For me, facing the Far East for the first time.

We finished the last of the brandy and shook hands and then raced on and on at never less than fifty along a British-made road of honest asphalt.

We slept the first night in Pakistan in a Government rest-house. At least, that is what it is called now. But the unmistakable design of it, the ancient but lovingly preserved furniture issued by some Edwardian barracks-officer long ago, the elderly, silent-footed servants bringing the early-morning tray of tea, were eloquent reminders that this was Single Officers Lines in the days when Dalgardin was something more than just a whistle-stop on the North-Western Railway.

It was all so exactly like a page from Kipling I swear I heard a ghostly cavalry bugle sounding “lights out”. . . .

Because it is apparently illegal for a Pakistani to bring a very second-hand car into his own country without a licence we ran into trouble at the Customs.

After a couple of hours of leisurely, dispassionate delay, while we sat and sipped green tea from cups made in Japan and tried not to fret, the precise rule and regulation governing such a situation was obtained. (The Pakistanis will have a regulation covering the Day of Judgement).

Finally we were allowed to proceed as far as Quetta 300 miles farther East – in the protective custody of a pleasant young policeman called Rahmanadin; a blue-eyed Pathan who, but for his turban and his grey nightshift of a uniform, could have passed as an Englishman.

This made it rather a squeeze on the front seat but we found it had its advantages. Travelling with a police escort gives you tremendous prestige in these parts.

From then on for a hundred miles, bowling along at a steady sixty over a thin ribbon of asphalt, it was all too good to be true.

This was the East stepping out of a Cinemascope screen, bringing with it the heat and the flies and the smells and the little Beau Geste forts and the swaying camel caravans carrying whole tribes down to their winter quarters.

Your first reaction is a curious one. But perfectly natural. DeMille has really overdone it this time, you think. And then you remember with a shock that this isn’t Hollywood. This is Baluchistan. And there to prove it is a signpost. One finger pointing East reads “Nushki 71½ miles”. And another pointing back the way we have come says simply “London 5,877 miles”. . . .

I had been warned in advance that finding your way round Pakistan is like playing a slow game of snakes-and-ladders.

So I wasn’t unduly surprised to find, after a non-stop dash from the border, that the dear old Duchess had been impounded by the Customs at Quetta until somebody could produce a bond that we wouldn’t try to sell her within three weeks.

This meant, for Rasal and Ali, two days of sitting about on hard wooden chairs, sipping innumerable cups of milky tea, until a magistrate could be found prepared to set his seal on a sheet of badly-typed foolscap and so let us proceed.

As for me, it meant a lost week-end in Shangri-La. Two lovely lazy days of lying in a long steamer-chair with absolutely nothing to do but listen to the fountain splashing in the hotel courtyard and shout after the bearer for another iced lemon squash.

Then we were off again on the last 500 miles, with the wheels spinning freely now over the good firm road.

Heading west for the first time in over a month. Leaving the mountains and the deserts behind for a lush green meadowland of lily ponds and giant grasses tall as palm-trees. A land where life still passes at the pace of the ox-cart, screaming and protesting on greaseless wheels as it has done for a thousand years.

No time now for more than a few sharply-etched snapshots.

Kites wheeling over a fresh-dug grave at Sukkar . . . women in red saris skimming the green scum from a little pond to fill brass pots with water . . . a naked boy stacking cakes of dried cow-dung into a pyramid higher than himself . . .

And then in a flaming sunset we were racing down into Karachi. Down an arterial road wider, busier than the Great West Road in the rush-hour. Past the tallest aircraft hangar in Asia, built for the ill-fated airship R101.

Then on through traffic that seemed to be making for six Cup Finals at once.

And suddenly it was all over. Ali switched off the engine for the last time.

Karachi came out to meet us with the sort of fulsome, overwhelming welcome that only the East can manage on the spur of the moment. But we were too tired, too numb with relief, to appreciate it. All we knew was that it was over. And tomorrow we could sleep all day.

So we had done it – 6,500 miles in thirty-six days. We had made it. With no more damage to the Duchess than a broken exhaust-pipe, a wonky headlamp and two burst tyres. And to ourselves? Well just a mild dose of dysentery each; and acute eye-strain through watching that road through the glare and the dust. And when it was all over just a simple, elemental desire to sleep for a week. We had used up 350 gallons of petrol: and had spent just over £100 each on food and fuel.

No records broken. Just proof once again that a good British car, well serviced and well driven, can take the worst road in the world in its stride. And where a car can go a bus can follow. . . .

For in a very definite sense this had been a historic run. The road we had followed – bad though it is for much of its length – is, by virtue of the Baghdad Pact, an inter-national highway.

A highway that will one day open up the East to the West so completely that runs from London to Lahore, from Birmingham to Bombay will be as commonplace as day-trips to Blackpool.

And so if it hadn’t been for that telegram I should never have known the amazing beauty of a Persian sunset. Or watched fifty camels drinking at the only waterhole in a hundred miles. Or seen the tomb of Omar Khayyam – a tiny green-tiled jewel set among date palms. Or learned to cook shish-kebab. Or tasted sherbet. Or bathed in the Arabian Sea.

But that’s how it goes. With Special Assignments you can be sure of only one thing: no two will ever be quite alike. All you know is, you are packed and ready to go. Anywhere. Anywhere for a story.

It may take you no further than a bus ride to the next town. Or you may follow it to the ends of the earth.

You start out to find a news story. And maybe finish up writing History.

Notes by Jerry F

1 This article was produced by my uncle in the late 1950s, I think for BBC Radio’s Children’s Hour.

2 It was later included in his book “Special Assignment”, published in 1960 by the long-defunct G Bell and Sons Ltd.

3 Not everyone today would celebrate the purpose of the journey described with quite the same enthusiasm as the author, but it must be remembered that it was a different world in 1957 and that, as the BBC frequently cautions, the article “may contain outdated views”.

4 The Duchess was a Triumph Renown.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Currently unavailable