Another chapter from “Special Assignment” by my uncle John Alldridge

(published in 1960 and now long out of print)

One august day in 1947 a young girl with long legs and a mop of unruly dark hair climbed diffidently up a flight of wooden stairs to the offices of the Mansfield Chronicle.

She was still wearing a school blazer. Only a week before one editor had glanced briefly at her gym slip, school tie and shapeless pull-on velour – and turned her down flat.

The second editor, David Greenslade, just out of the R.A.F. and sympathetic towards the young and enthusiastic, pointed out that he really wanted a boy but agreed to give her a chance.

This willingness to give sixteen-year-old Margaret Pycroft a chance was no doubt prompted by her eager promise to try anything once, go anywhere and do anything.

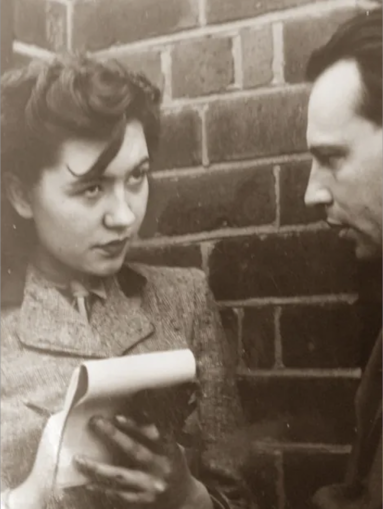

Margaret ‘Maggie’ Pycroft,

Unknown photographer – Courtesy of Kate Nicholas

On the very first day it resulted in her being marked down on the office diary for an inquest. To any reporter with the slightest experience, covering a coroner’s court is known as ‘easy meat’.

But to young Maggie, who had just taken her school ‘cert’ and had never been inside a court of any kind, the experience was terrifying. For one thing, she had not the remotest idea of the difference between an inquest and a post mortem.

Throughout the sombre procedure, as witnesses were questioned on that hot summer afternoon, she was waiting for the body to be produced, dissected and discussed before her eyes.

In fact her terror was so complete that she absolutely forgot to take a note of the proceedings and returned to the office convinced that she would get the sack.

But she didn’t get the sack. And now, twelve years later Margaret Pycroft each morning climbs an impressive flight of stone steps leading to the head office of one of the big national newspapers.

She has been to nearly every country in Europe, had her name splashed in big letters across the paper’s main feature page, covered top news stories and wined, dined and chattered with scores of famous people.

On that first day when the inquest misfired she never dreamed of reaching Fleet Street. She just dug her toes in and kept to the promise of having a go at anything.

For a long time, it was a life of weddings, deaths and funerals, village council meetings, weekly calls on the vicar and seasonal fetes and fairs at local churches.

Then she was given a wonderful chance. The town had acquired a repertory company called “The Argosy Players” and the paper decided to send a critic.

Maggie liked plays, read books about theatres in her spare time and even acted in amateur dramatics, so the office decided that she would in future devote each Monday night to a seat in the stalls at Mansfield Palace Theatre.

With relish she took over her allotted 6 inches of space and with glee saw her initials appear in print for the first time. Looking back she often boggles at the nerve she had in those days, alternating between fiery condemnation and lavish praise.

“I wonder they didn’t sue me, but they were great troupers,” she says.

Nearly every Thursday when the paper was printed one of the players would appear at the Chronicle demanding either to see the editor or to take her for coffee, according to the temperature of the week’s ‘crit’.

In those first years she had often heard her elders and betters refer with reverence to something called a by-line. But it wasn’t until she left the local paper and joined The Star, an evening paper in Sheffield, that she had an article signed with her own name.

It was given to her on a story that brought her face to face with tragedy for the first time in her life – the great pit disaster at Creswell in Derbyshire.

Reporters from all over the country had been rushed to the little village but she was one of the few newspaper-women on the spot.

The office had instructed her to leave the factual reporting to her male colleagues and seek out some story that would bring home the personal element of the tragedy.

It was a grey day with a cobweb mist over the red-brick village. They were still bringing up bodies at the pit-head and because she was a girl she was turned away.

For a time she wandered through the narrow streets, empty and sad with curtains drawn at every window. Then as she walked past the village school came one of those moments blessed by every reporter. The moment when the whole story falls into place. The moment of inspiration.

Through the open windows of the village school, she heard the sound of children’s voices whispering their morning hymn. They had not yet been told of the terrible thing that had happened. But nearly every one of them had lost a father or a brother. The words of the hymn were haunting and poignant on that grey day – “God bless the miners who work in cheerless gloom. And when their daily toil is done, God bring them safely home”.

Cresswell Schools, Creswell, Derbyshire,

Brewill and Baily architects – Public domain

She scrambled into a phone box and dictated the story of the Creswell children. When she opened the paper that night she saw the story spread over a whole page, with the magic words ‘by Margaret Pycroft’ in print for the first time.

Since then she has worked for one of the most important evening papers in the North of England, the Manchester Evening News, and for the past four years she has been a feature writer and news reporter on the Daily Herald.

Her assignments have included other major tragedies.

She flew to Germany to expose the misery and desperation of the thousands of refugees who, years after the war, still live in camps, cut off from normal life and forgotten by the world.

But she still has a very special feeling for that Creswell story. It showed her for the first time that one humble incident often gives a clearer and more vivid picture of an event than a mass of detail.

And it taught her that if a woman reporter is going to specialise in what is called in newspaper jargon ‘the human story’, she must above all things keep in her heart the warmest sympathy for the people she writes about.

But tragedy is only part of the story. When a newspaper-woman begins her career by promising to go anywhere and do anything she is bound to end up with some crazy jobs.

That is undoubtedly why Maggie one day found herself bound for Paris as chaperone to fourteen darts players from a little dock-side inn in Salford, Lancashire.

Bus drivers, dock workers, labourers, bank clerks – they were all crack players and members of a team that had become famous for its prowess. The boys had decided to show the French how to play. They saved up to make a tour of Paris. Their wives were being left at home, but the Herald persuaded them to take Maggie as chaperone, translator and guide. She also had to file a story every day.

They went by bus to London carrying the precious dartboard in a brown paper bag. Then they flew in an old Dakota to Belgium and went on overland by bus to Paris.

For four riotous days the fifteen of them whizzed around Paris. Every hour of the day brought a crisis. Someone got lost on the French Underground, and Maggie had to find him. Another champion had a violent bilingual argument with a gendarme, and she had to keep him out of jail. They had to be kept intact for the great moment of the tour – a match with the glamorous Lido girls from the plushiest nightclub in Paris.

Pic 3 – The Lido girls (aka The Bluebell Girls), with their founder Margaret Kelly, in 1948,

about the time of the darts match against the team from Salford

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Margaret Kelly Leibovici with Bluebell Girls, year 1948,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

When the night of the Lido tournament came round one of the Herald’s Paris reporters promised to help, and succour came in a most unusual way. Sid, captain of the team had cut his finger and it had turned septic. Maggie decided to take him to the British Military Hospital in Paris.

When a doctor lanced the finger, a sympathetic young officer asked her what on earth she was doing as guide and counsellor to fourteen strapping men.

When she explained he offered to fix a game for them in the N.C.O.’s mess that night so that she would know they were all together and safe. She accepted readily, and a sergeant called Jock promised to deliver them to the Lido club at the appointed hour. Feeling happy and confident she went off to put some pictures on a plane for England and deal with a photographer who didn’t even know how to say ‘hello’ in English.

At ten o’clock that evening she sat sipping coffee with the Paris reporter in the Champs Elysees. Half an hour went by. No darts team. Then suddenly she spotted the troops, with Jock at the head, coming up the Champs Elysees. They were all gloriously full of British Army beer and had almost forgotten about the match that was to give her the most important story of the tour.

After delivering a hasty lecture to Jock she grabbed her precious charges, bullied them into a café and poured black coffee down their throats by the gallon.

The boys were soon aware of what had happened and rallied within about five minutes. Trying to make amends they were full of old-world courtesy at the Lido Club, kept apologising to Maggie, and let the girls win. She will never forget her last glimpse of them, setting off arm-in-arm down the Champs Elysees, hugging the dart board in its brown paper bag.

The Paris reporter had disappeared. She had gone to have a cognac to steady her nerves.

Jobs like that have always happened with alarming speed. One fine evening in June, Maggie was flying to Scotland to do a rather boring routine story.

She stepped off the plane at Renfrew Airport to hear her name being called on the loudspeaker. It was the News Desk in Manchester. She was told briskly; “Maggie – you’ve got to find yourself a sailor.”

And that was how the story of the ‘Cinderella in Bell Bottom Trousers’ began.

When she got her breath back she gasped: “A sailor? What on earth for?” The business-like voice at the other end explained that the Duke of Argyll was throwing a ball for the Fleet at Inveraray Castle.

But the order had gone out ‘no bell bottoms’. It was to be a ‘pukka’ affair, with full-dress a ‘must’ and tickets 3 guineas each. So the man at the other end of the phone ordered: “Find a perfectly ordinary matelot – and take him.”

She will never forget Mac’s look of astonishment when she told him the plan. He was a fine 6-footer from Abbotsinch Naval Air Station just outside Glasgow, and he was scrubbing the barrack-room floor when he was picked out as her escort.

He had simply volunteered for ‘duty ashore’ without having the remotest idea what the duty entailed. But he had no time to back out. She collected him in a shining black limousine, whisked him off to the tailors and fitted him up with white tie and tails.

That night they drove in style up the gravelled path to the fairy-tale castle, hereditary seat of the Clan Campbell.

Mac pleaded for a tot of rum, then squared his shoulders and marched along the red carpet with Maggie on his arm. They had become good pals, so as they went in through the massive hall with its glittering armoury she whispered: “Keep your mouth shut, Mac. You’ve got a cockney accent that would ring the Bells of Bow.”

They were introduced to the Duke and Duchess at the head of the great hall. Then Mac got the shock of his life. Standing beside the Duke of Argyll was the Admiral, magnificently blazing with gold braid and holding out his hand to Mac.

For the first and last time that night the sailor lost his nerve. He looked the Admiral straight in the eye, gulped and murmured: “Good evening, your grace.”

But no one guessed his identity all through that magic night. The sailor Cinderella danced under the chandeliers with the moon gleaming through the tall windows of the ballroom; he drank champagne with Highland chiefs, ate turkey and lobster in the old castle kitchens.

But before the clock struck twelve the woman reporter had to rush down the wide drive leading to the lochside and phone her story from a draughty telephone box.

It was dawn before Mac was driven back to the naval barracks. As the sailor was driven through the gates the guard gasped with disbelief. His eyes travelled over the white tie and tails and drooping white carnation. “Where’ve you been,” he demanded. “I’m Cinderella. I’m just coming home from the ball,” grinned Mac. . . .

It is an important part of a reporter’s job to persuade reluctant people to talk. Most of the famous are only too willing. Maggie has warm memories of sitting quietly in a corner of a theatre bar with Noel Coward, being invited to breakfast by Jack Benny, having a zany telephone conversation about golf with Danny Kaye, and discussing the difficulty of writing a book with Graham Greene.

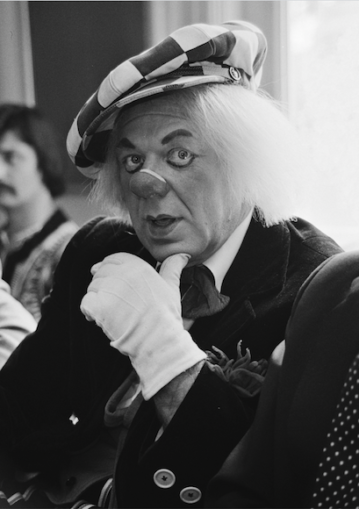

But one that nearly got away was Popov, the great Russian clown. When he first came to England with the Moscow State Circus, Britain raved about the pale young genius who seemed to have inherited the mantle of Grock.

Everyone wanted to know more about him. How old was he? Was he born to the circus? What was he like in private life? It seemed as though all these questions would go unanswered.

The interpreters and protectors who surrounded Popov wherever he went refused to let him be interviewed. Apparently, in Russia personal glory was frowned upon. Although Popov was the moving genius of the circus he must be treated the same as the lowest-paid little acrobat.

But Maggie, who had seen him perform, was so intrigued that she determined to ‘get her man’. For days she followed him round with the full circus entourage. He was never alone. And it was also obvious that the only English he knew was – “O.K.”

She took with her a friend who spoke Russian. This friend made a tactful approach through one of the youngest interpreters. At first he ignored her requests. But after two or three days he volunteered the information that Popov would be alone that afternoon. He was going to the fun fair.

They found the great clown gleefully driving a Dodgem car, free at last from the everlasting guard. Only one escort watched him from the side of the track.

Maggie eventually talked the escort-interpreter into asking Popov himself if he would speak for a few moments. The clown refused. She repeated the plea at regular intervals of five minutes.

Then to her astonishment Popov climbed out of the little car, came across to her and said brusquely through the interpreter, “Come then. A few minutes.”

It turned out to be one of the most difficult interviews of her life. Popov, his long fair hair falling over his pale moon face leaned back in a chair and glowered. It turned out that the only questions he was willing to answer were about the circus. Any personal questions he brushed aside with: “Why should you want to know that?”

Then suddenly to Maggie’s astonishment, her friend poured out a violent stream of Russian. Popov blinked, looked at her like a chastened small boy and from that moment began to talk, more freely.

Russische Staatscircus in Amsterdam,

Hans van/Anefo – Licence CC BY-SA 1.0

The reporter heard all about his home in Moscow, his wife and his little daughter who was already showing promise in the circus. He told her the things he liked about England and the things he didn’t like. The sort of food he ate – and how often he allowed the barber to touch that magnificent mane of blond hair.

Gradually the picture assembled. They parted on the warmest handshake.

Maggie had her story and nearly jumped over the Dodgem track with joy. “What on earth did you say to him?” she asked her friend. “Oh I just told him to behave and stop talking like a naughty schoolboy,” she giggled.

You would perhaps think that the jobs that a woman reporter looks back on with greatest pleasure are those which present all the glamour of wealth and high society.

She certainly enjoys an occasional job that is thoroughly feminine. Assignments like the wedding of the French Ambassador’s daughter, or sipping champagne on the terrace of the Embassy residence in Millionaires’ Row, or talking to Pierre Balmain, who dresses some of the loveliest women in the world and watching him fascinated, as he unpacks a dress worth £3,000 from a sea of tissue paper.

But it is what reporters call the ‘off-beat’ stories that are always remembered with most affection. They have often been done in appalling weather conditions in the utmost discomfort and difficulty. But looking back they seem wonderful assignments.

For instance there was the time when the office asked Maggie to do a full-scale investigation into the life of the miner in modern society. At first the assignment sounded dull. But it proved to be quite the opposite.

After she had spent days talking to miners and their wives at the pit-head, by the fireside and in their clubs, pubs and favourite haunts she received an invitation to round off the series by going to the coal face herself.

Few women are actually taken to the coal-face. Miners, you find, have an old superstition about allowing women below the surface. But an exception was made for Maggie and so one Saturday morning she found herself dressed in dungarees, pit boots, a helmet and pit lamp, with one sweat rag round her hair and another round her neck, ready to plunge below.

It was what is known in mining as a ‘hot pit’ where the temperatures reach 90 degrees at the coal face and the cheerful Yorkshire miners were doubtful whether she could last out even the two hours underground.

But she did stick it out; and hacked off a lump of coal from the gleaming face to prove to them that she hadn’t cried off. She was shot to the surface again with a black face, bruised knees, perspiration streaming down her back – and a small lump of coal clutched triumphantly in one hand.

They grinned at her with delight and shouted good-naturedly, “You’d have to do better than that if you were on our shift!”

***

Glamorous occasions? Margaret Pycroft can’t remember any that gave her a greater thrill than standing in for the Queen Mother at a Royal Variety Performance in Manchester.

This is how it happened. Maggie had been sitting through the rehearsals, chatting to stars like Liberace, Al Read and Arthur Askey as they came off stage after doing their turns.

Suddenly a technician grabbed her arm. “How would you like to stand in for the Queen Mother?” he asked. “Just go up into the Royal box and stand there until we put the lights on you.”

She had no time to argue and found herself reclining in the royal chair wondering what was going to happen. Then the full glare of the fierce white lights that are called ‘limes’ flooded the box. She felt lonelier and more embarrassed than she had ever felt in her life. Fellow reporters in the stalls called out, “Wouldn’t you like to be there tonight?”

Well she was there on the night, saw that the lights had been adjusted to give a perfect illumination and the Queen Mother was seen to perfect advantage by the whole theatre.

Maggie was in full evening dress and stiletto-heeled shoes and longed for the plush and gilt chair she had tried out in the afternoon. But at Royal charity shows members of the Press have either to stand or sit on the stairs – unless they pay for their own tickets!

There is always glamour too when film and stage stars are around, but more often than not she catches them in unconventional circumstances.

Once when she called to see Margaret Lockwood, the lovely lady had her hair pinned up after a bath. The day jack Benny invited her to breakfast he greeted her at the door in striped pyjamas, dressing-gown and monogrammed slippers – with a rumpled newspaper in his hand and spectacles on the end of his nose. She says his charm made up for everything. And when she interviewed coloured singer Harry Belafonte, he had to whisper the answers because he was suffering from laryngitis.

But a reporter lives on the unconventional. That is why she jumped at the chance when her office told her to catch a boat to Barra in the Outer Hebrides and do a story on the J. Arthur Rank film unit that was just starting to shoot Compton Mackenzie’s “Rockets Galore”.

Half the technicians and actors went over with her in the tiny steamer that called in at all the little islands delivering letters, provisions and struggling, bewildered sheep.

They found when they got there that most of them would have to live with the crofters, for there are few hotels in that remote part of the world. And the wonderfully friendly Hebridean people immediately decided to make the city-dwellers stronger and healthier by feeding them on carageen, the sea-weed sweet that the Queen once tried when she went there. You have to taste carageen before you understand why Maggie nearly caught the next boat home.

Maggie had a colourful and lively story but she also had one of the big problems that always torment a journalist on an out-of-the-way job. She could telephone her story easily enough. But there were some wonderful pictures taken in crofts and on the wide silver sands of Barra. And for days there seemed no way of getting them off.

The boat didn’t sail at the weekends on its usual trip to the mainland. The French fishing vessels that sometimes touched Oban weren’t going either. The last plane had left. And there were no helicopters.

She tried to charter a plane and found it would cost £40 – and in the end just had to gnash her teeth and explain to her office. But eventually she found a few pictures had got through on an early plane. The rest just had to be used as ‘stills’ for the film people.

One of the most recent assignments she has been given brought her greatest worries about ‘getting copy over’. She was sent on a non-stop tour of refugee camps in the East. Within six days she covered thousands of miles, often far from a cable office and feeling as though she had reached the end of the world.

But as she looked at her diary – “Athens, Nicosia, Beirut, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, Beersheba, Tel Aviv . . .” she felt all the frustration and irritations were worthwhile. “In what other job would a woman be given such a marvellous chance to see the world and gain experience of life in every aspect?” she asks.

But she has never forgotten the days when the diary on the news desk read instead – “PYCROFT. Smith’s funeral. Brown’s wedding. See Vicar. Rural District Council….”

Note:

From Wikipedia –

Creswell Colliery mining disaster, 1950

In the early hours of 26 September 1950, a damaged conveyor belt caught in a machine at the colliery, causing the motor to overheat and catch fire trapping 80 men beyond the flames. They all perished as a result of the fumes and smoke.

Jerry F 2022