InfoGibraltar, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Your author has enjoyed the extracts posted recently by GP from his uncle’s work, reflecting on older fashioned journalism. The extracts titled ‘The Lady Reporter’ and ‘The War Correspondent’ suggested this response.

Imagine, if you would, being appointed a rookie reporter on the Daily Telegraph. Imagine, also, that it is 1939 and the awfulness of what is to come already pervades Europe. Further imagine that you are posted to Poland. And that you are one of but a very few women journalists working for national newspapers.

This is the story of Clare Hollingworth, who is described above. Aged 27, she was posted to Katowice, close to the German-Polish border in August 1939. She reported a massive build up of tanks along the border: three days later, she manages to place a phone call through to the embassy in Warsaw to tell them that the Germans bombers were over Katowice and that there was anti aircraft fire in the streets around the hotel. “Impossible, Miss Hollingworth”, the embassy number two, still half asleep, says, “Herr Hitler has assured us all that there will be no invasion while talks continue.” Gloriously, Clare holds the phone out of the hotel window, lets him listen to the noise and then replies “That sounds like war to me.”

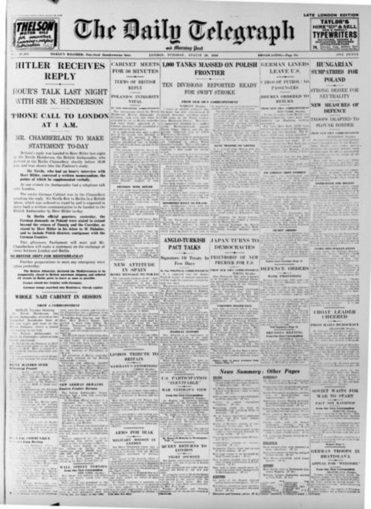

It is something for a journalist to break an exclusive story. But imagine now that you ask Clare what was the biggest story she ever broke. “I broke the Second World War”. Some scoop. In the restrained tone of the times, the Telegraph published the tank build up story on the front page as the second lead story. And the byline was ‘from our own correspondent’.

Clare’s career took her to war zones in Vietnam, Aden and Palestine, and eventually to cover the Cultural Revolution in China. She accumulated a vast list of contacts which gave her work genuine insight, particularly during the 1970s in the time of Mao.

Hollingworth stayed in China until she retired to Hong Kong in 1981 aged 69. She was hugely respected at the Foreign Correspondents Club there, for her work, her contribution to professional life at the club, and eventually for her longevity. Stories of her at FCC, where I later met her, abound. She was back in China in 1989 and observed Tiananmen Square from an overlooking balcony. She apparently went to sleep with her passport under her pillow into her nineties in case there was one last event she had to see, one last story she had to write.

I did not meet Clare Hollingworth until she was over 100. By this time, she was frail and her sight was failing. She came into FCC very regularly, during the day and with two helpers. Her favourite table was in a corner of a sectioned off quieter glass lounge near the entrance known as ‘the bunker’. She was always keen to hear the news and many members of FCC would read newspapers to her because of her eyesight. On one occasion I was with a committee member and was asked if I would do so. Of course I would. There followed some twenty minutes of reading from the Telegraph, and the Times, but also from the (Singapore) Straits Times and the (Hong Kong) South China Morning Post. At the end, she said “You read well, young man, but your role is to report news, not interpret it.” Advice for the current generation of newsreaders, perhaps.

Clare Hollingworth died aged 105 in 2017. The page from the Telegraph above is framed and above her table at the club together with a simple plaque by way of memorial. The club established a more substantial memorial by way of a fellowship in her honour which now supports younger journalists. One of the first recipients was Jessie Pang, a young Hong Konger. She wrote in 2019: “I aspired to be a foreign war correspondent, but then my home became a conflict zone”. One can only wonder what Ms Hollingworth would have made of the war on her doorstep during the now suppressed protests. Clare’s memoirs, ‘Front Line’, were published in 1990.

© Hongkonger 2022