More notes from 45 years of cycling

In its day, Tinsley Marshalling Yard in Sheffield was the world’s most advanced railway-wagon sorting centre. It specialised in computerised hump-shunting, which is not a fetish category on Pornhub but refers to the technique of gravity-rolling unsorted wagons down a short slope and siphoning them off one by one into different sidings to build up rakes of wagons with the same destination. The computerised bit was the processing of speed and braking-distance data gained from track levers the wagons tweaked as they slid down the hump slope. This did away (I think) with manual wagon-braking, a practice characterised by the kind of gruesome injuries that you might expect when your job is running alongside moving heavy machinery while poking about in it with a ten foot pole and simultaneously jumping over sleeper heads and lineside cabling.

There were quite a lot of superlatives attached to this facility, which once handled 3,000 wagons a day and had its own dedicated class of heavy shunter, but the thing that astonishes me about Tinsley is not its throughput, but its age. The yard opened—opened, not closed—in 1965, soon after the Beeching Report shut down half the railway network, containers were being developed, and motorways were fanning out across the country. Yet the authorities deemed there was a big future in rail freight. Beeching, believe it or not, actually opened Tinsley. I wish I could say economic forecasting has improved since then. But it hasn’t.

Tinsley lasted two short decades, before dying a long, slow death. Now it must be one of the largest brownfield sites in the country. It is as big as a town, nearly two miles from end to end. You can see a lot of it from the M1 at Meadowhall (and from almost nowhere else)—a couple of solitary active tracks picking their way amid the weeds and gravel heaps. Redevelopment has only been partial and large tracts still lie derelict.

Harringworth (Welland) Viaduct

“Welland viaduct, Rutland” by x70tjw is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

In urban settings, the Victorians never put a foot wrong architecturally. They left us some fantastic town and market halls—Bolton and Rochdale, and Accrington market hall, to name three unsung ones in just one county. Even their warehouses were built like stately homes.

But in the countryside, just about everything they touched they ruined. England’s glory is its vernacular architecture: the stone cottages in the limestone country, the brick and flint in the chalklands, pantiles in the lowlands, timber-framing in the West Midlands. And then along came the Victorians, throwing up their boxy townhouses everywhere with no regard whatsoever for the local building tradition, disfiguring village after village with horrible engineering bricks and incongruous and pretentious gothicky embellishments. These things look great on pump stations and cotton mills. They don’t on cottage walls.

The one exception to this blight is their railway infrastructure. Rural Victorian stations are nearly always charming, and Victorian viaducts are the Roman aqueducts of our time. The best-known in England is probably the Ribblehead in the Dales. And lowland England has Harringworth Viaduct, the longest viaduct of all and the finest sight in Rutland, though half of it is in Northants. It spans the valley of the Welland, in a pastoral tract of the Midlands, and also crosses a trio of disused rural branch lines. You get a distant view of it from the A47 between Peterborough and Leicester, but a special journey is required to get a good look at this 1,275 yard, 82-arch structure. It was completed in 1878 by the Midland Railway, at a cost that in today’s money would buy a space station, not to mention the many gruesome injuries and deaths among the navvies. (For a lovingly compiled list of drops from great heights and machinery manglings and so on, see https://www.harringworth.org/history/the-railway-viaduct/). The viaduct remains in use to this day, though mainly for freight and people whose poor life choices have obliged them to live in or go frequently to Corby.

I discovered Harringworth twice. The first time was on a bike ride in the Leicester Wolds. The second time I was on a train. Having nodded off on a Midland Mainline service to Derby, I woke up as it crossed the viaduct on a works-related diversion and thought I was still in a dream: our express was edging at roof gutter height through the middle of a beautiful stone village I did not recognise, as if I were on a magic carpet in a Harry Potter scene. The village was Harringworth, one of a constellation of beautiful villages in this well-heeled undulating limestone area, which is actually an extension of the Cotswolds. And so to

Scunthorpe

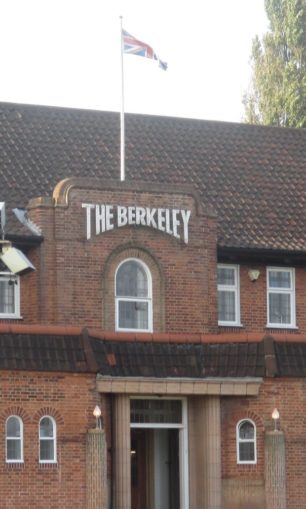

Don’t laugh, Scunthorpe really is interesting. It’s not just a Victorian shanty town tacked onto a steelworks in the wastes of north Lincolnshire. Did you know, for example, that this is a garden city? The suburbs really do feature 1920s-style broad grass-verged avenues and generously proportioned houses that occupy plots about three times bigger than today, and which are very easy to get lost in on a bicycle. There is some fine interwar architecture, including The Berkeley, a roadhouse-type pub (a breed of often neo-Georgian, Art-Deco-ey hotel-boozer often found at interchanges that has almost entirely vanished for some reason).

But Scunthorpe’s main drag really is dismal. A long, low, straight, litter-strewn shabby-commercial street nearly devoid of buildings of interest, and also of English-staffed establishments. It’s a great place to brush up your Polish, Latvian, Albanian, Farsi, Arabic, Bengali, Gujurati, Romanian and many other exotic languages. The war memorial plaque by the library carries over 600 names for both wars, nearly all British, and as always, I had to wonder, is this what they died for?

The first time I rode through the place, in the 2000s, I got talking to one of the old steelers. Quality control man for 18-19 years and one of the first to be made redundant in the Thatcher years. Did a course in Doncaster to train as a lorry driver steelyard, came back to find the plant was gone. So he used his redundancy to take his two kids on a world sailing trip. Unemployed for five years, finally getting work in a hospice. He thought Thatcher was right to close down steel plants, because “low quality was a real problem,” but wrong about the way it was done. “You have to do something like that gradually.” Over ten thousand people lost their jobs in Scunthorpe in the 1980s, he said. “I went in one morning and my job was gone and they gave me the cheque. The unemployment offices had hundreds of men queuing outside them. They weren’t prepared. And we steelworkers had a stigma on us, because we were seen as the cause of the collapse, which affected everybody, and yet we had been well paid and had got redundancy payments. Others in dependent industries didn’t. The stigma still hasn’t entirely gone.’

He deplored the waste of expertise. “Scunthorpe had experts in construction pilings, a mainstay product. Yet we buy stuff from the Germans that we could and should be making ourselves. We gave away our technologies to visiting Japanese delegations in the sixties.”

All very regrettable, I agreed, but what about the gruesome injuries? “Oh, plenty of them. I watched a colleague break both his legs one day, horsing around with conveyor gear while a beam was being moved.”

The Scunthorpe steel industry owes its origins to one Canon Cross, vicar of nearby village of Appleby, who first discovered ironstone in the Frodingham district in the 1840s. In time, it became Britain’s biggest steelworks, which is why I have included it on my curiosity list. In this out-of-the-way corner of a rural county, you can still see what is, I think, the biggest working industrial scene remaining in the country—actually, visibly making stuff in volume and emitting tons of CO2-laden smoke. The train to Cleethorpes runs through and along the edge of it, and a truly awe-inspiring sight all those black sheds, towers and conveyors make. This was once how half of urban England looked—the workshop of the world. Now, Scunthorpe is more or less all there is left.

I am going to end this without even mentioning the town’s problems with Internet porn filters, which is known in the computing world as the “Scunthorpe problem” and is deeply irritating to locals, who anyway use the charming moniker Scunny for their home town. The official name actually means “homestead of Scumbag,” a Viking lord. Or something like that.

For my free downloadable pdf travel books on Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: https://www.itabibito.com/.

© text & photography except where indicated Joe Slater 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Currently unavailable