Christianity in Korea—Just Why?

The Catholics formed the vanguard of Christianity’s march into East Asia. They first arrived in Korea in the late 1700s, and met with the same hostile reception as they had in Japan and China. (If you want to know the gory details of what they went through in Japan, look up the “Shimabara Rebellion”). Some five thousand converts and priests lost their lives over the long years of persecution and martyrdom in Korea. The spreaders of the Word achieved little. At the end of the nineteenth century, Korea seemed destined to remain an ideologically Confucian and nominally Buddhist backwater, with a small and very resilient Catholic community.

But then two things happened. Firstly, the Japanese took over the country. Secondly, the Protestant sects of America, seeking avenues of expansion, caught the sweet smell of opportunity. They realised they could win over ordinary Koreans by supporting them against the hated colonial power. They could support them morally, and also offer their churches as gathering points and places of refuge, all with the implicit backing of American power. They also had the strategic nous to base themselves in the cities, not the countryside, which was Buddhist and Catholic territory. Not only were the cities competition-free, but they were also growing fast as the Japanese built up the infrastructure they needed to control and exploit Korean resources and assimilate the people. The Japanese did not much like or trust the Christian church in Korea, but did not seek to exterminate it, despite some well-publicised atrocities. They were more worried about the communists and other openly political foes. Soon, little red crosses were popping up on urban skylines across the country.

The missionaries’ strategy worked brilliantly. Protestantism displaced Catholicism as the standard-bearer of Christianity in Korea, and eventually so eclipsed it that many Koreans came to regard it as the only true form of Christianity, and Catholicism as a kind of unsound, deviant faith.

Yet the real boom came after the war, after the Japanese had been kicked out. The Presbyterians took the lead, followed by the Methodists. At some distance behind were the Baptists and other sects. Churches went up all over the country: dark hulks in the villages and towns, with spires like factory chimneys, and, in the cities, modern complexes more like conference venues. The missionary flow was reversed: an army of ten thousand Korean envoys of God went out into the world. By the 1990s, there were eight million Korean Protestants.

Why did this flowering happen? After the war, the Protestant churches continued to benefit from their reputation as defenders of the people against tyranny, and shrewdly sided with democracy protesters in the years of dictatorship. The popularity of America as South Korea’s security guarantor also played a role. And some Koreans, like some Chinese, believed that adopting western religion was one way of achieving western levels of development. At the same time, a spiritual void opened up in Korean life once people no longer had to worry about keeping a roof over their heads. Buddhism had declined to little more than a set of rituals, and could not fill it. Christianity could.

Korean Christianity is fundamentally different to Christianity in Europe. The faith does not have deep roots in Korean soil. There is no bedrock of churchgoers who are “culturally Christian” — the half-believers, mostly elderly, who in west Europe keep the rural churches open, who are Christian mainly because they were christened, and because the spire, the cross and the bible have formed part of the fabric of their community all their lives. By contrast, many Korean Christians are bible-bashers, fired up with the zeal and the ecstasies of the born-again. Cycling through the backwaters of North Gyeongsang province years ago, I walked into an empty convenience store to buy food and drink and found the idle counter girl poring over a book. She was a teenager, so I assumed it was a comic book or something to while the time away with. Looking over the counter while she was at the till, I saw it was the Old Testament.

Staying in Suwon in 2017, it seemed to me most Korean Christians felt more comfortable with the Old Testament and the more fundamental stuff. It seemed too that music was a key part of it. Korea is the most musical society in East Asia, the one place where you hear music of all kinds everywhere. In big churches, you often see drumkits and guitar stands as well as keyboards. The singing attracts children as well as their parents, and that helps keep congregations youthful. My Korean teacher said that it was the music and social life that initially drew her to the church, and that it was ten years before she began to seriously study the bible.

The full travelogue, Uri Nara, can be found at:

https://www.itabibito.com/ (bottom left on the home page)

Images:

Suwon Jeil Gyohoe (Suwon First Church)

Autumn colours at Hwaseong

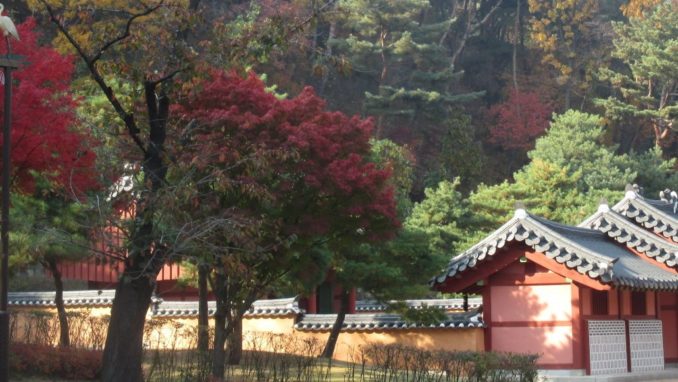

Korean temple

© text & images Joe Slater 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file