Lausanne, 2014

Back in the 1980s, I had been in Switzerland mainly to make a bit of money and “have an experience.” I hadn’t really been too concerned with the politics or culture of what is in fact one of the most interesting countries in the world. Well, now I was passing through and had about ten hours now to make amends. The breakfast waiter, whom I had to myself, would be a good place to start.

He was in fact a Frenchman, resident in Switzerland for 20 years, having moved here for the higher wages and “better quality of life.” Overall, though, he thought Switzerland was no longer such an attractive proposition. He mentioned in particular the health system, which, like many things, operates under a unique model — it is fully privatised, with everybody having to buy policies from private insurers (there are subsidies for the poor). This enables full freedom of choice, within certain coverage and cost limits, but, he said, it takes a big chunk out of salaries. Rents too were now enormous — as high as the equivalent of 800 or 1,000 euros a month for a one-room flat.

“If you have money, it’s OK, but the little people are complaining now.”

Nonetheless, he said, the Swiss were still better off than the rest of Europe.

“Don’t you sometimes think the Swiss are better off at the expense of the rest of Europe? After all, their industries benefited enormously from the reconstruction after the war.” (And during it, I might have added. The Nazis used Swiss banks extensively, and Nestlé was chocolatier to the German armies).

“Maybe, but as far as I’m concerned, they pay it back by spending their money abroad. They’re constantly going abroad to relax as their own country is so small. It can get a bit claustrophobic here, you know.”

I asked him about Switzerland’s unique system of direct democracy, in which citizens vote up to four times a year on national policy proposals and nobody outside the country can name the leader. This system has many admirers, particularly in small, politically excluded parties across Europe. The waiter was not so impressed.

“It may look democratic and fair to outsiders, but it’s actually very cumbersome. They have seven presidents, for Pete’s sake, none serving for more than a year. Think about it.”

I did. If Switzerland had a Mount Rushmore, that would mean about 169 huge carved heads (all but a handful male, incidentally). It would mean you could have charity Pro-Former Swiss President Golf Tournaments. Later, when age took its toll, there could be Dancing with Former Swiss Presidents with Dementia evenings. (Joking aside, there actually is a “Living Former Presidents Society.”)

Being Swiss President sounded essentially like a gap-year job. One year was hardly long enough to remember where the printer ink refills were kept. Foreign dignitaries would keep calling you by the previous guy’s name. So would some of your own dozier aides. They probably got an orientation package when they took office, ending with the lines “we hope you enjoy your work experience here and we wish you every success in your future career.” Perhaps the waiter had a point.

The referendum system is interesting, though. Results over the years have highlighted the strong work ethic and hard-nosed — not to say extreme — conservatism of the Swiss people. Three-quarters of voters rejected universal basic income in 2016 (a truly remarkable result — has any other people in all history turned down free money, by a 75% margin?). Longer holidays and Sunday driving also got the thumbs down (that ban may have since lapsed). About half of Swiss voters approved a proposal to cut back asylum-seeker numbers; this narrowly failed, but another referendum enabled minaret construction to be vetoed. Perhaps the most startling vote was the one that allowed women to vote. It happened in 1971, a mere 80 years or so after female enfranchisement in New Zealand. And even then, one of the 26 cantons held out for men-only voting until 1991.

* * *

Not surprisingly, as Basel looks like a small, pretty, well-heeled German city, Lausanne looks like a small, pretty, well-heeled French city. From the shore of the lake, it rises gently up a mountain slope, dominated by the cathedral perched on an outcrop. This would have looked superb in fine weather, but today it was a rather forbidding mass with a tower that merged into the clinging cloud. I stayed in the commercial streets below, which were dotted with heavy nineteenth-century monuments to Swiss enterprise like the Banque Cantonale Vaudoise.

As said, the feel was French, but you knew it wasn’t France from the street names, which did not commemorate great victories or generals, but had names like Avenue des Acacias. And also from the scarcity of graffiti or litter and the lack of a visible underclass. And you knew it from the phone boxes. Switzerland has the cleanest, shiniest phone booths I have ever seen anywhere. I went into one to make an international call, and found myself sensually stroking pristine metal surfaces, as if it were an art installation. I examined my forefinger: barely a speck of dust. The metro was just as spotless.

Yet there was something missing here, and that something was a history. The main upheaval Lausanne seemed to have experienced in two millennia was the 1791 “banquet des Jordils (I’m not sure what a Jordil is)” commemorated by a stone tablet at the Eglise Évangélique Réformée with a long list of prematurely dead people. For a moment, I thought they’d all been poisoned by the salmon soufflé, but it turned out they had been celebrating the second anniversary of the French Revolution. This had roused the ire of Their Excellencies of Bern, solid protestants and no friends of the ungodly commie fanatics in Paris, and resulted in a flurry of executions.

Switzerland has an altogether peculiar national story. Its neutrality goes back centuries. It has not fought in a proper war since the early 1500s, yet its army and its mercenaries were feared and respected by all Europe. (That said, it pursued its own little civil conflict in 1839 so incompetently that most of the nearly 100 fallen were killed by friendly fire). To this day, it retains conscription and its menfolk keep firearms at home. At one point, Switzerland seriously considered building a nuclear bomb. (So, curiously enough, did that other rather vainglorious neutral, Sweden.) But its most powerful weapon has always been its geography. Without that, it is hard to see how it could have avoided piecemeal annexation over the centuries, by France, the Habsburg Empire and what were to become Germany and Italy.

That geography, and its ethnic differences, also dictated Switzerland‘s unusual political history. Its regions never really coalesced into a true nation state. It was a confederation of fiefdoms for centuries, and remains one under the mantle of nationhood. Its neutrality is buttressed by a reluctance to join international organisations, which, paradoxically, has made it the location of choice for international organisations.

* * *

“By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept,” wrote T.S. Eliot when composing The Wasteland, and I wasn’t feeling so great either that afternoon as I peered out across a sheet of steely grey water backed by mist-wrapped mountains. A lone windsurfer drifted about on the breezy, rain-pocked lake, just about staying upright. It kept pouring down and I could feel a cold coming on now. But I had a considerable wait for the next boat over to Évian, in France.

I pottered about a bit among the fine old hotels along the shore, dabbing my nose. Then I went over to the tourist office and pestered the lady on the desk for half an hour. There was one thing to thank the foul weather for: I had no competition for her attention.

She said there was a daily traffic of commuters crossing the lake from France, known locally as “les Frontaliers,” paying their taxes and bills in France, while making all their money in Switzerland. It didn’t look to me like a good deal for the Swiss.

I asked the tourist guide how the Swiss French viewed the French.

“They call them “les grandes gueules” (the big-mouths; the 1965 film of this name was translated as The Wise Guys). Still, people do tend to orientate themselves culturally towards France.”

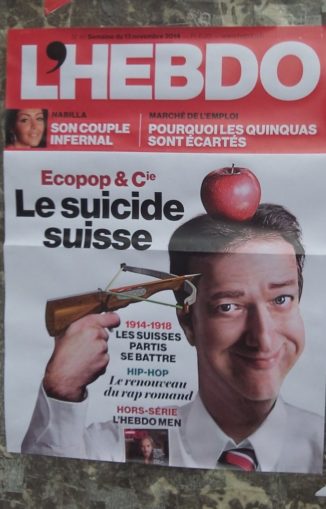

That was clear from the selection of magazines in Lausanne’s newsagents. The way the three flags of Belgium, France and Switzerland were often displayed together in Lausanne also suggested a kind of informal francophone solidarity.

“And how do you get on with the Swiss Germans?”

“They find them a bit narrow and work-obsessed. A bit restraints. The Swiss French are more open than the Swiss Germans. What I mean is, they venture into German-speaking Switzerland more than Swiss Germans come here. Also, many non-European immigrants are francophone, and those that aren’t find French easier than German to learn, so that attracts them here and makes for a more cosmopolitan society. And there’s the UN in Geneva.”

She sounded like a native French speaker, but I was struck by her use of “they.” It turned out she was a Swiss German. Her fluency in French was, to me at any rate, unusual — nobody up in Graubünden had known French well. Nor was there much sign of the German language or its speakers here in Lausanne. The French-speaking world ends abruptly at the line between Bern and Basel, she said; in the border area, neighbouring villages could have different languages. But relations between the two groups were fairly good, even though there is one awkward problem.

That problem is mathematical. As people do everywhere, the Swiss often vote in ethnic blocks, meaning that the French and Italian Swiss can always be outvoted, even together, because an absolute majority of Swiss are German-speaking. This isn’t such a problem for the Italian Swiss. Though they account for just 8% of the population, that level is high enough to ensure they are always taken into account. But the French Swiss, with a quarter of the population and territory, have little more ballot-box power than the Italian-speakers. This rankled.

Despite these divisions, a unique shared history and culture, and a deep-rooted sense of national identity, have enabled Switzerland to avoid the intractable acrimony of the French- and Flemish-speaking Belgians.

Like the breakfast waiter (and like a good few of the magazines I had noticed around town, with cover straplines like Le Suicide Suisse), the tourist lady feared Switzerland’s best days were behind it.

“Standards have been slipping recently. There’s increasing unemployment, and the children are not as neat and tidy as they used to be.”

* * *

The approaching ferry was in view now. At the terminus café I looked out over the wet tabletops, onto which overflowing gutters dripped loudly, then beyond the drooping flags and pot plants out to the lake. You could just make out the mountains of the French shore.

There was a customs office at the ferry terminal, but it was unmanned. I boarded without any check, joining a group of briefcase-wielding Frontaliers.

Looking back at the roofline of Lausanne as we sailed away, I suddenly thought, for no obvious reason, of Bratislava. What on earth did they have in common? I had visited both for only a day. There was a superficial resemblance: both were pretty, medium-sized political and cultural centres and roots deep in European history. But it was the differences that brought it to mind.

Bratislava was once Hungarian. Then it became German-speaking. Since 1919, it has been Slovak, and since 1993 the capital of Slovakia. It was repeatedly invaded. It had known glory and shame: Hungarian kings were crowned there once, but it was the main city in the only country that had actually paid the Nazis to take away its Jews. Bratislava had a story. Lausanne had nothing like this to look back on. It had grown fat off the peaceful centuries like a firm of silky solicitors, while Bratislava was the penniless reprobate, the villain and victim of history. The proud piece on the Habsburg chessboard and, under communism, the prison city looking out enviously over the Austrian border. I found Lausanne pleasant, but no more. Bratislava left a mark.

On the other hand, if I had to choose between working in Lausanne or Bratislava, I guess I would go for the place with the Swiss-franc salary.

We reached Évian in an hour or so. I found a hotel for half the price I paid in Lausanne, draped my wet clothes on the radiator, and got into the bath. Then, refreshed, I went out and double-checked I was in the right country.

For my free downloadable pdf travel books on Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: itabibito

© text & images Joe Slater 2020

For my other free downloadable pdf travel books on Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: iTabibito.com.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

микрозаймы онлайн быстрый займ на карту сбербанкав кармане займ личный кабинетзайм с текущими просрочками оформить быстрый займ на картусмс займ онлайнзайм под залог недвижимости срочно