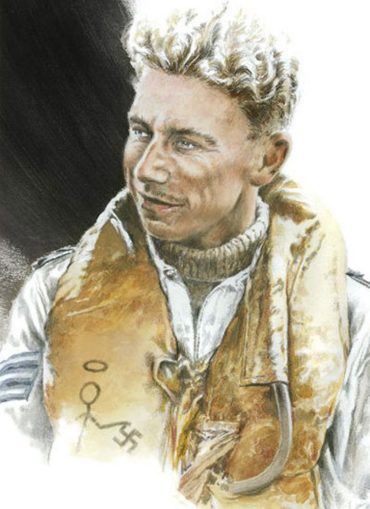

Artist Geoff Nutkins. With permission.

At Chelsfield, local folk were well aware that a Hurricane had plunged from the sky above them on that sun-kissed Sunday afternoon of 1 September during an intense and frightening period of activity that shook the Village. One witness reported seeing the pilot slumped forward over his controls in the cockpit as the aircraft dived to earth, its wings shearing off and debris scattering when the fuselage buried itself with unimaginable force and a thunderous crash in a crater of chalky soil in an orchard at the corner of George Whitehead’s field near the Warren Road-Court Road crossroads.

ARP wardens stationed nearby logged the tragedy in just a few sparse words:

“14.10 – Between Warren Road and Court Road opposite Court Lodge Farm – Plane on fire – British plane crashed.”

Over the previous five minutes they had already recorded another five incidents. Two high explosive bombs fell at Hawstead Road [Lane], killing one cow, wounding another and causing damage to “Woodlands”; two more HE bombs behind Chelsfield House damaged the property and wrecked an old farm building; three HEs between Chelsfield Lane and Skibbs Lane left a dog and calf dead and another calf wounded; two landed between Chelsfield Lane and Court Road; four exploded in an orchard north-west of the Warren Road-Court Road junction.

In the aftermath, Royal Artillery soldiers were posted to guard the site of the plane crash by day but it was three weeks before a civilian salvage squad at AV Nicholls and Co in Brighton received curt instructions from the RAF: “COLLECTION ORDER: Hurricane L2062. Chelsfield, NNW of Sevenoaks.”

Arthur Nicholls, well used to grim jobs like this, knew what to do. He found the Village constable at Chelsfield and was directed to the only place the policeman knew of on his patch where a Hurricane had come down – George Whitehead’s field. The RA boys told Arthur an RAF team had cleared the fuselage two weeks before and had said they would come back for the engine. Arthur reported that he’d located L2062 “at the junction of the crossroads adjoining Court Road and a road called Highways [The Highway]”. A propeller blade was embedded in the bottom of the crater, he wrote, the engine was still in the ground, a few pieces of smashed fuselage remained and his gang would deal with it all on 23 September.

When his crew duly began digging, they came across a flying boot with a foot still inside, and an unopened parachute. Then they exposed the pilot’s body – and called the police. Three constables – the Village bobby and two from Orpington – watched as the men dug further, found two shillings and eleven pence ha’penny in coins then took a cigarette case and a small wallet containing a photo of two women from the pilot’s pocket. These they handed over to the policemen, who, Arthur reported next day, also took charge of the pilot’s remains while the salvage gang filled in the crater.

Astonishingly, nobody seems to have checked the Hurricane’s engine number or identified the dead pilot. The plane was presumed to be L2062, as per the Collection Order.

On 5 October the foot was buried at Star Lane cemetery at St Mary Cray in a Commonwealth War Graves Commission grave marked “Unknown Airman”. Shortly after the salvage operation, it has been suggested, more body parts were discovered during tidying up – or possibly were found by gipsies scouring the crash site for scrap metal. Certainly, parts of another “Unknown Airman” were interred in a CWGC grave at Star Lane on 12 October. No connection was made between the two finds at the time, however. Unfortunately, police records were destroyed long ago and burial registration details yield no clues.

In fact, Hurricane L2062 was indeed shot down in the area during the Battle of Britain action on 1 September. The pilot was Flying Officer Bryan Noble of 79 Squadron based at Biggin Hill, who baled out wounded and landed in a water-filled pit on the Marley sand and gravel site at Riverhead (where Tesco and the Lakeside Place housing estate now stand). Badly burned, the 24 year-old pilot, former pupil of Emanuel School, Battersea, was taken to Sevenoaks Hospital, underwent surgery and survived.

RAF inspectors dispatched to look at Noble’s machine, which had crashed near Broughton House at Dunton Green, noted the type of plane and its serial number for recovery purposes but confused matters by identifying the place where it fell as “Chelsfield, NNW of Sevenoaks”. Nothing of this error came to light at the time, however, and thus the scene was set for the subsequent mix-up and bewildering chain of events that occurred five miles away.

Some time in the early 1970s, two enthusiasts from Halstead Aircraft Museum are believed to have done some excavation work at the site of the wreck, though this was never admitted. What, if anything, they found is shrouded in mystery. Despite denials, it has been suggested some items were taken away.

There things rested until October 1992 when Mark Kirby, a member of the former Wealden Aviation Archaeology Group, conducted a dig at the crash site without a Ministry of Defence licence but with the consent of the landowner at Chelsfield and the family of Sgt Hugh Ellis. He was also helped by information provided by Andy Saunders, an aviation researcher and author of several books on WW2 mysteries with an impressive track record. Saunders had looked into Ellis’s disappearance and uncovered puzzling discrepancies around the Chelsfield crash.

The Wealden Group, eager to establish the facts about the Hurricane buried in the orchard, identify the pilot if possible and discover where his body had been removed to, had been granted permission to excavate the site in 1980. But this was withdrawn soon afterwards with no explanation except that the MoD considered there were “over-riding reasons why this site should not be subject to excavation”. The Protection of Military Remains legislation of 1986 made it unlikely the go-ahead would ever be given again.

Regardless, Kirby was determined to unearth some answers. On Saturday 24 October 1992, in a biting wind entirely in keeping with one suggested derivation for the name Chelsfield – “Chilly Fields” – excavation began in the presence of Sgt Hugh Ellis’s relatives, including his cousin Peter Mortimer whose own investigations had convinced him of a link between Hugh and the Chelsfield crash.

Proceeding carefully and respectfully, Kirby was able to retrieve a quantity of bones, part of a Mae West life jacket, a flying glove and an assortment of aircraft parts. Crucially, a section of the engine cowling delivered the vital clue: stamped in one corner was P2673 – the very number of the machine assigned to Sergeant John Hugh Mortimer Ellis at Croydon in 1940.

Excavation was halted; the police were informed. A coroner’s inquest on 6 July 1993 formally identified the remains and declared that John Hugh Mortimer Ellis had lost his life on active service as a result of enemy action. Mark Kirby was not prosecuted. Sadly, Hugh’s father died in 1947 and his mother in 1951. They – and Hugh’s heartbroken fiancée Peggy Owen – passed away without knowing the truth about his fate.

On 1 October 1993 a funeral service was held for Hugh at the RAF church in Uxbridge. His erstwhile commanding officer Peter Townsend, by then 79 years-old, living in France and unable to attend, asked for flowers to be placed on the grave on his behalf. He spoke of “a marvellous pilot” with skill, courage and unfailing cheerfulness and specified flowers of blue for the sky, yellow for Hugh’s hair, white for the flying overalls he always wore.

After the service, Hugh’s remains from Chelsfield were taken to Brookwood military cemetery in Surrey and interred in the RAF section in a CWGC grave with full military honours. The inscription reads: “One of the Glorious Few. Finally rested 1. 10. 93 Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country). The two “Unknown Airman” graves at St Mary Cray were left undisturbed.

The coroner ruled that Hugh’s burnt flying glove, the piece of his Mae West lifejacket and a valve from his Hurricane’s engine found in the Chelsfield excavation should go to the Shoreham Aircraft Museum, where they are still on display.

Nearly 15 years later, on Saturday 17 May 2008, Hugh’s memorial stone at Chelsfield Green was dedicated in a moving service conducted in steady rain. It was as if the sky was crying for that golden youth whose life had ended so violently a few yards across the field 68 years before …

By Patrick Hellicar, for the Chelsfield and Farnborough Local History Groups, May 2020.

© Audrey’s daughter 2020

FOOTNOTES: I have to confess that my article is based largely on the work of others, rather than my own original research. Much of the information has come from books on RAF activities in WW2 and – notably – Finding the Few: Some Outstanding Mysteries of the Battle of Britain Investigated and Solved by Andy Saunders (published by Grub Street in 2013). Details were also gleaned from a variety of websites. To confirm or colour-in the overall picture, so to speak, I’ve relied on resources including the 1939 Register, the Operations Record Books of RAF Squadrons and 85 Squadron’s Combat Reports for 1940 held at the National Archives, plus records of wartime bombing incidents that occurred in the Chelsfield area and some personal memories. There are still a few elements of the story that I think need to be resolved, but exploring them may take a while.

When we’re allowed out again, if you haven’t already been to the Shoreham Aircraft Museum, it’s well worth a visit. It is dedicated to the airmen who fought in the skies over southern England during the Second World War and offers more than just mangled lumps of metal and bits of engines and armaments to look at. The hundreds of artefacts and documents, letters, photographs and eye-witness accounts exhibited there really do give a sense of how these courageous young men operated and what they endured. It’s right on our doorstep – and you can get a nice cup of tea and a slice of home-made cake there too!

Curator Geoff Nutkins tells me he is devastated that the coronavirus restrictions have curtailed openings and events the museum had planned to mark the 75th anniversary of VE Day. It would have been a big year with the Battle of Britain in focus too, he said. The museum was due to unveil the latest of its RAF Memorials Project stones on Friday 24 April opposite St Peter’s Church at Ightham, but due to the coronavirus situation this had to be postponed. That memorial remembers Flying Officer Malcolm Ravenhill, who lost his life on 30 September 1940.

Close to us, you can find other memorial stones to some of the fallen Few at Sparepenny Lane, Eynsford; at Noah’s Ark, Kemsing; and at Main Road, Sundridge.

The museum’s website is at http://www.shoreham-aircraft-museum.co.uk/

© Patrick Hellicar 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file