“It depends what you are hunting, but yes we started to increase our defences, most of all in the last dozen years or so. We had some wealth now to invest in trade with our new friends, to improve our buildings, our farms, our health, but only slowly. And then he came and saw, and was trusted. What was agreed I can’t say, but he left, and then we began to import through our friends from the Middle Sea more new goods, purely for trade with Logres, items highly taxed there on which we could make a good surplus. He helped us, knew the right people, so that none of it could be traced back to us, and then the wealth began to flow and we could do the things we needed more quickly, and begin our work outside.”

“My God, you’re smugglers! Is that what was in the warehouse, drugs? Please no… I don’t believe it!”

The others just waited, stony-faced, leaving it to Iltud to find the words. He nodded miserably. “Yes, we smuggle, just like the forebears of our neighbours in the outside in former times, but not drugs, not things illegal in Logres, only those highly taxed where the government keeps most of the surplus. We do not touch drugs. Mainly cigarettes and tobacco, light and easy to transport, very profitable and easy to sell, less commonly gold and silver, antiquities and old things of value, fuel sometimes, that’s all, nothing bad, I swear.”

Sally looked at the others. Martha was all business, Petroc didn’t seem to see what the fuss was about, Gillian was blushing. “Gillian, how could you go along with this? How could you? Is he telling the truth, no drugs?”

She nodded. “I know, it took me that way when I first found out, but that’s how they found you by the barrier, they were sending out a few cartloads of cigarettes when they heard the sounds, came to look and discovered you and your child. If they hadn’t been smuggling, no one would have been there in time.”

Sally didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, the relief of it compared to her worst fears; it was like something from Compton Mackenzie. They were smiling now, as if the worst were out and she hadn’t exploded, the smiles becoming grins, she began to giggle, it was just too absurd, and she a policeman’s wife. It was a wonder their laughter didn’t wake her son.

They calmed down over another tea. The mood was lighter in the room now, the storm had broken. “But those things you need those terrible weapons for, what are they?”

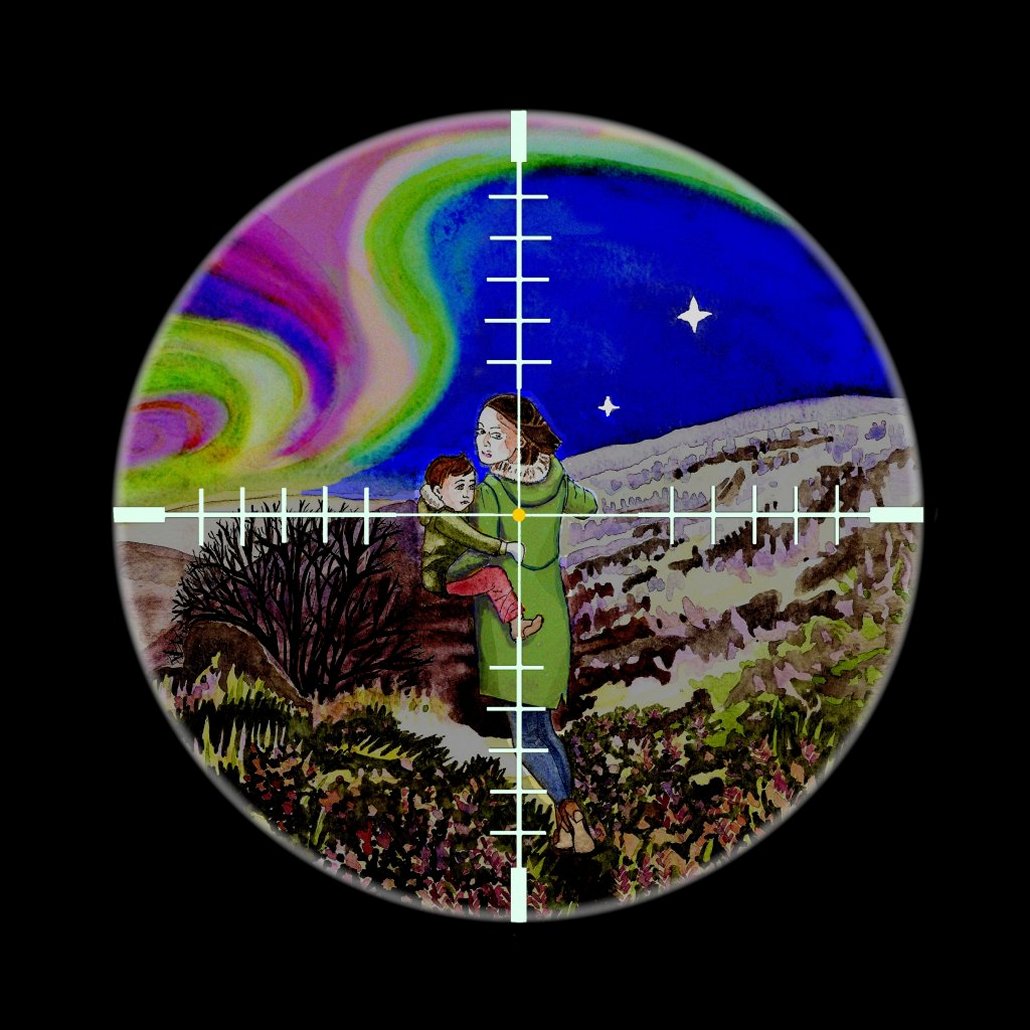

“You know we call them the Guardians. If they have a name for themselves or if God or the Devil does, we know it not. We know little of them, where they come from, where they go, what they are. They seem to avoid large armed parties with lights, but hunt the weak and the defenceless as they press in; trying to break the barrier, but it holds them and always has. However, when the barrier is weaker, when it is pushing out, expanding, they seem to become more furious, more active. They must take several of those who would otherwise find us each year, but we do not know how many.

Only once have we cornered one, when I was a boy. One seemed to break into the world, the outside world on the moor and spread terror, killing hundreds of sheep in its fury. Fearing what its presence could lead to, the Council decided to track it and end the threat before the outside world could. They sent our best hunters out and they searched just beyond the barrier and found where it lay up in the day when it was not out hunting. They dug a great pit and covered it with heather. The fog was thick that night and the creature fell into the pit, it was leaping up, trying to escape and it very nearly succeeded. The hunters, fearing to draw attention by firing their weapons, poured fuel into the pit and set it alight before piling the earth back on top, they then fired the surrounding moorland heather to hide their traces and returned. One of the hunters told me that it looked like a great starved black dog, with orange shining eyes and a coat of shimmering black, almost indistinct in the mist. Those hunters are all passed now; it was a long time ago. That’s all I know, I swear.”

A pack of feral dogs then; she had heard the stories from her early childhood, the Exmoor Beast the press had called it, speculating it was an escaped black panther. And then it disappeared and the killings stopped suddenly. “So, we are safe here, they can’t get far this into the Pocket?”

He nodded his answer. He was opening up at last, if somewhat reluctantly, goaded on by his wife. “Why is everyone so ecstatic I have brought a young child, what’s so special?”

Gillian laughed. “It’s not what you fear, some sort of secret pagan cult lusting after the blood of young children.”

Sally crimsoned in embarrassment that they might think that was her suspicion, it hadn’t even occurred to her.

“It’s just that most who come here are people like me, refugees from life, damaged, older, unable or unwilling to have children, or they do not meet the right partner.” She smiled at her husband. “It must be over seven years since the last child came here; it is regarded as a blessing and augurs good fortune, a sign of better times ahead, that’s all.”

“And this about ‘being touched’ whatever that means, before someone can leave?”

“It’s true,” added the Doctor, “I’ve not been, have not asked. Why would I want to leave?” She looked at her husband. Real love there thought Sally, I’m happy for her.

“Few ask for it, many of those who do are refused. Some who do not ask are asked to receive it. It is our way; our leaders’ wisdom chooses who is least likely to go astray in the outside. Martha and I haven’t been asked; Petroc has, but refused.”

“Why would I want to go outside when all I want is here?” Yes, real love she thought.

“Very, very few incomers ask. Most are fleeing the outside; they don’t want to go back. A few are asked when they are trusted, after many years. You know about the others who ask and are refused, yes?” She nodded. “The touching requires the blessings of the Abbot and the approval of the Duke himself, it takes place in the presence of some ancient relics, and only happens on Easter Day at noon. Why this is, I again know not. That is all.”

“Relics, what relics, even Catholics stopped believing in them years ago? It all sounds like mumbo-jumbo, there must be more you’re not telling me.”

He shrugged his shoulders in resignation and looked at his wife. “I did not say you would believe, but I’ve told you all I know, that I swear.” He seemed to view that as the ending of his obligation to give her the answers she wanted.

“Just one more please Iltud. You say you have spoken truthfully? Then tell me about the man from outside whom you and Brother Peran have mentioned, the one who came fourteen years ago, met the Duke, was touched and left, and has since helped you with your criminal activities.” She instantly regretted using that word; it was snide and unlikely to help coax him further. He winced and looked at his wife again.

“I can tell you little more. It was as you say, that’s all. It is not encouraged to gossip about it, the Abbot says it’s unholy.”

“But Brother Peran said there was prophecy, talk he was a man sent back. That’s nonsense, isn’t it?”

His face was flushing with anger now, she was being unfair. “Let monks and priests have their prophecies, I have to live in the world of today, as it is, as should you. All I know is he was a man, a good one with a dying spirit they say, who came just before one Easter, met the Duke, was touched and left, that is all.”

She felt spent, as if all the burning questions and fears had evaporated, leaving just a few fading embers to blow away in the breeze. The cheering thing was that they had seemed easier, more ready to share information, even if so much had ended in frustrating admissions of ignorance. Most of all, her hostess was starting to treat her as one of them, who had rights, who should be respected as an equal. She had no doubt that Iltud would not be far behind, in so many things it was becoming clear that his wife led the way.

Just before she went up to bed, Iltud caught her eye. “Because of your blizzard of questions, I forgot to give you the important news, the Council want to meet you on Monday in the harbour, St Josephs. You’ve no choice I’m afraid, that’s the way it is. We can help you prepare over the weekend and I will take you down if you like.”

Helena’s door phone buzzed. She went over to the camera screen; it was him, alone, just standing there as if he had all the time in the world. She pressed the door release and watched him come into the foyer of the building. He would be knocking on her door in two minutes; she smiled. He was late, most unlike him. She realised she was excited to see him, spend time with him again, to hear his, their, news. She went to the hall mirror and looked at herself, ran her hands over her dress to dislodge any invisible creases.

She knew she was still attractive to men, still a few years to go to her forties she reflected. She couldn’t bear to let herself go, get sloppy; she was too much of a control freak. She had made an effort for him, for friendship rather than desire’s sake, although she knew that lurked away in some subterranean passage deep within her, waiting its chance to coming screaming out and damn the consequences. The others, they want what they see in me, power, wealth, elegance perhaps, even looks, things for them to enjoy, to possess. Unlike him, who wasn’t at all interested in any of those things. His motives were entirely different, if only… Her doorbell rang. Stop, pull yourself together, you’re acting like a schoolgirl on a first date.

She opened the door. There he was, standing in that way of his, smiling that slight smile, waiting silently for her permission to enter. Always the same. She motioned him in and closed the door. “No one followed me here,” he said as she took his coat, not remarking on the metallic weight in one of the pockets. A habit she had picked up in recent years, an almost instinctive desire to check.

She led him through to the kitchen where they would dine. He seemed to prefer the informality of eating there, as if it were a family supper in his own home. Part of her wished it were, not only the part she had just thrust back into its locked lair.

He refused the glass of wine she offered him, apologising for having to go back to work later, then apologising again, more profusely this time, for being late and keeping her waiting. She would not drink on her own, so poured them both mineral water. He looked up at her again; his smile was back and his eyes were studying her face for any sign of thought or emotion. It really was disconcerting, almost flattering, this scrutiny.

“You saw of course. Pleased?”

“Of course, as long as they are safe.”

“They are, no one has a clue. Innocents hurt, some killed, sadly, but not by ours. It’s miraculous to me, they had to improvise quickly. We owe them so much.”

The cynical professional side to her had to have its say. “As does the Board of the company targeted I understand, only they want to pay off their debt in specie.”

“I know, they mean well; it’s all they understand I suppose.”

He suddenly looked tired, as if the stress he must have been shouldering, like a giant piece of blotting paper absorbing it from those around him so they could focus on the task, had suddenly sucked the strength from him. She knew from her own life that a sudden successful conclusion to something long pursued could wash away one’s energy in a flood tide of relief rather than exultation. She reached out tentatively and put her arms around him, holding his still form close, her head on his shoulder. She didn’t, couldn’t, find the words, rarely could with him. She pulled back, “Come on, let’s eat, too much longer and we will be using it as footwear.”

© 1642again 2018