© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

If you’d visited Madrid’s Prado Gallery in the early 1980s, about a decade previous to (contrary to the artist’s wishes), it’s star attraction Picasso’s Guernica being moved to its own museum, you may have noticed a couple, conspiratorial before a Hieronymus Bosch as if tourists.

For churches and galleries, she is wearing a pleated skirt, almost to her ankles, and a black long-sleeved top. He, long sleeves also and gallery smart jeans. They are in their early twenties. They whisper to each other. She holds a mid-range Japanese compact camera behind her back. He clasps his hands behind his.

If you stray too close to them, they will make an excuse and move on, making a loud and jolly remark about a Bosch grotesque from the artist’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

“Guy with the balls like bagpipes,” she will say in a girlie New Jersey accent. “Gross.”

It is myself and Tammy. We are on a mission. She has just, having been inspired by Hieronymus, declared the pair of us to be God; knowers of all, bringers of retribution.

As we prepare to address a Rubens, she whispers to me exactly what I want to hear, “As soon as we get back to the hostel, I’ll show it to you, promise.” Playfully, she adds, “Hush, don’t tell.”

* * *

They say that, because of the microscopic nature of such things, every single human male seed produced in the entire history of mankind could fit into a milk churn. Likewise, despite being the biggest cell in the human body, all of the female matching version might fit into a teachest. Through the ages, keeping the teachest and milk churn away from each other has been a challenge vigorously addressed.

Tammy could escape from the nun’s hostel but could not get past the brothers. In mimicking her efforts, I could get past the brothers but not the nuns. We did the best we could. We stood on the landing between the young men’s and young women’s dormitories, in our nightclothes. She was inseparable from her compact camera. She stood fiddling with it, listening to me.

“I still haven’t seen it?” I reminded her.

She pretended to take my photo.

“It’s pointless going any further until I know it’s here.”

She told me to smile and turned the camera portrait ways.

“We’re supposed to be going tomorrow,” I reminded her. “It’s a waste of time if we’re not properly equipped.”

She smiled, held the camera up and dropped it while moving her hands behind her back. I stooped to make the catch, very gingerly, just before the camera hit the marble floor. I held it towards her but she wouldn’t take it back. I realised her game.

“Wow,” was all I could think to say as my jaw dropped. I juggled the camera, regarding it closely, terrified I might damage it.

“Really?” I asked her.

“Sure, that’s why it’s important.”

“Wow,” I repeated.

“It’s just like an ordinary camera,” I noted.

“You’ve heard of the silicon chip?” She asked.

Of course I had.

“It’s all about the chips,” she said. “And knowing how to use them.”

“And the film?” I asked.

“Don’t worry about the film, let me do my job.”

I juggled it some more. Was it heavy? Not really. I looked into the lens. At my level of understanding, a lens is a lens, is a lens, is a lens. I passed it back to her.

“I was expecting something military, blocky, camouflage colours with a manual six inches thick.”

“Nope,” she announced. “Now tell me about your side of things. It’s called ‘Operation Swaling’?”

“Swaling means a cleansing fire. Like burning the remains of the crops. The Spanish burn the fields to kill all the voles. Remove the pests.”

We were interrupted. There was a lock-up at eleven-thirty. She shrugged. We air-kissed. The all-seeing and all-hearing brothers and nuns returned us to our respective bunks.

* * *

The next day was a sightseeing day around Madrid. We spent much of it separated, following each other about, ironically in order to make sure that we weren’t being followed.

At supper time we were back at Madrid Chamatin station with our packs for another overnight train, heading further south. This time we did have a compartment to ourselves. The train being light of passengers, closing the compartment door and pulling down the blinds did the trick. We sat opposite each other, made ourselves comfortable and addressed some serious massaging of each other’s dirty feet.

“Now I want to see yours,” Tammy announced. “What’s this all this about?”

When I started my service, I lodged in the Dolphin Square residential complex in Pimlico, handy for Westminster. I had a corner room at a corridor end, meaning that I could see down two streets and the length of one corridor, simultaneously. There were observable comings and goings which, as my understanding of routine settled, began to form a pattern.

There was lots to do, perhaps one day I will tell those tales too. For the time being, suffice it to say, I spent half of the day being lectured at, or in meetings, and the other half following up leads, doing research, often into the middle of the night, sat at my desk in Dolphin Square. I moved that desk next to the windows. I even had a pair of field glasses.

I had a colleague, a Welsh girl called Williams. She was rather plain, for no reason other than she didn’t make the effort to dress or make-up. An NCO’s daughter, she’d spent half of her childhood as an army brat council house kid and the other half at a more than respectable boarding school.

Despite being on the same grade, mine was the higher salary, men being better paid than women in those days. In so much as she’d been in the service for longer than I, she was the more senior. If something cropped up, she was the “go to”, rather than me.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Tammy interrupted.

That didn’t mean that Tammy wasn’t enjoying herself. The Americans loved the impenetrable nature of British culture, especially if it involved class-based elitism with a hint of scandal. If delivered in a deadpan conspiratorial English accent then so much the better. Tammy looked at me gooey-eyed, lapping it all up while everything I said went over her head.

There was a full-sized art deco swimming pool at the northern end of the Dolphin Square quadrangle. A bistro sat to one side of it on the next story up. I would enjoy a swim and then socialise in the bistro afterwards, although discreetly keeping myself to myself. I wasn’t a big drinker or a great conversationalist, either then or now. Williams did likewise. It was good politics to be seen out and about and not to be lumbered with the reputation of being a hermit. Not surprisingly, the bistro attracted Dolphin Square residents, politics and Civil Service types, some media, even the occasional minor royal. The apartments were subsidised for what, in today’s money, would be described as higher-ranking “key workers” and for what has always been known as the “right type” of person. Noticeably, there was a certain euphemistic discrete indiscretion amongst the swimmers and drinkers.

“Can we dumb this down a bit please?” Tammy asked. She was starting to look somewhat blank. A two hundred page manual on the CIA’s latest miniature “concealed by ubiquity” camera (and its associated mega-sensitive film), might have been easier for her to understand than upper-middle-class London’s goings-on.

“One or two things, unmentioned, became a bit obvious,” I explained.“Some of the clientele were rather theatrical in their behaviour,” I confided, twisting her big toe in a circle.

“Gee.”

I reached for her little toe and gave it a squeeze, “And some of the cast members were rather young.”

“Neat,” she decided.

She reconsidered.

“Gross,” she muttered upon reflection.

* * *

“Miss anything?”, I asked, wiping the last of the sleep from my eyes. I was returning from the train toilet cubicle having completed an obligatory once every 24 hours full-body wash and shave, having used only the equivalent of a cupful of water.

“The city walls, must have been Cordoba.”

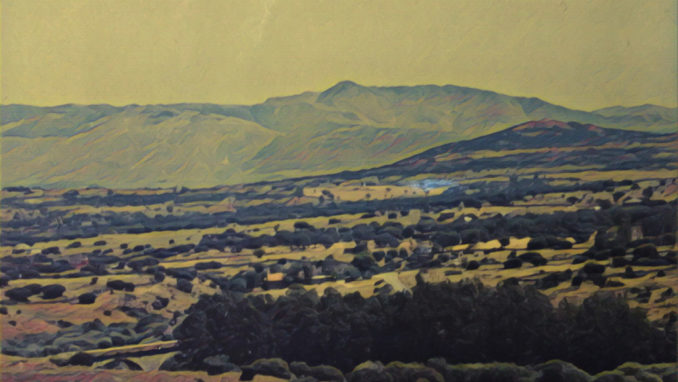

By now, the sun had risen. The countryside was cultivated but arid. An occasional field was completely scorched, an occasional other, irrigated to dark green. Mountains lay in the near distance. Across the next couple of hours, we passed through those mountains and into a much more fertile area, close to the Mediterranean sea.

Upon arrival, Algeciras station consisted of a concrete box terminal at the head of long, but uncovered, low platforms. In the gentleman’s manner, as usual, I volunteered to carry Tammy’s pack. A shambles of food vendors were strung out on the roadside. We had greasy chicken for breakfast. So greasy that it soaked through the little cardboard boxes and left a fatty trail of dots behind us as we walked through the bleach-blocked concrete streets, heading for the ferry terminal.

The actual ferries were on strike. We sat on the “travel side” of the port, on the edge of the harbour, clutching our tickets in hope and expectation. A scrawny Muslim man unrolled his mat and began to pray nearby. We dangled our legs over the side of a jetty. Gibraltar lay to our left-hand side. In the haze, in the distance, rising from the flat, the Rock looked like a giant sleeping elephant.

We looked ahead, across the horizon towards another continent, towards Africa.

“You were saying?” she instructed.

To be continued…..

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file